Un Paseo por el Valle

Until a couple weeks later when Apollo killed him out front of the Yacht Club and it all came out that he wasn’t no retired Special Forces commando after all but just a two-bit meth dealer running from a misdemeanor failure to appear on DWI charges up in Oregon, we knew the man as Shadow, the only name he ever gave for himself. We get a lot of passers-through in paradise that put-on airs of mystery, and the way I look at it we’re all pretty much running from something, so it’s a common courtesy to not ask too many questions of ex-pats that drift through. Anyhow, this man that called himself Shadow, who would turn out in death to have the more mundane name of Randall Simon, and who claimed over beers with Joey Kayak some five hundred and thirty-two confirmed kills in Viet Nam, had first shown up about three or four months ago and palled up with Captain George and Apollo. They let him stay with his dogs in a camper trailer on the Yacht Club lawn out back on the edge of the mangroves. But Shadow had not been around for a few weeks now, and George was laid low and headed downhill in the semi-final stages. For his part, Apollo had a rotating gaggle of boys that tended the lawn and kept the place clean and followed him around town. He rented out camping space on the Yacht Club lawn and pocketed the money that was supposed to go to Old Man Barton, who was back in the States at the moment and getting more senile with each new trip down. It wasn’t an actual Yacht Club, of course; that was just Old Man Barton’s dream, and he had nailed up this ship’s wheel a few years back to one of the giant trees in the front yard and painted on it the words “Yacht Club,” which had a better ring than “Barton’s place,” or “Babbling Bart’s shotgun shack.” It leant the beachfront property a kind of dignity that it warranted, and though it started off as something of a joke it grew through the years into an actual place name that you can still find in some period guide books even. Of course, that was before Apollo finally stole it away under squatter laws a few months after Old Man Barton’s only son—and heir apparent—got sent up for ten to twenty down in Panama on a smuggling rap, a legally condoned theft that was likely the nail in the old man’s coffin, he loved the place so; anyway, Old Man Barton was pushing daisies less than six months later. But those are all different stories altogether; it really was a beautiful beach front plot, even if the shack Barton built was a terrible eyesore that took him over five years to just get dried in and never did get finished; it would surely have made a lovely setting for a real-life yacht club that to this day continues to elude our lovely little backwater of Puerto Jimenez.

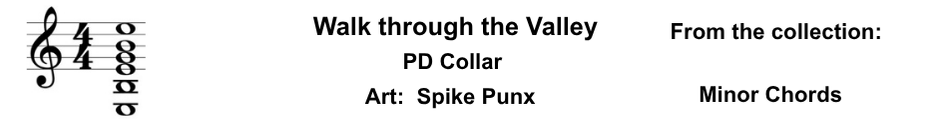

So, there I was on a Sunday afternoon tending the shop while Silvia took lunch when Shadow comes traipsing suddenly in. I was reformatting Number Six at the end of the line of public machines, and he waltzes up and plants himself next to me at Number Five. It takes me a second to recognize him crossing the floor; his head is newly shaved, he is bare-chested and wearing a sarong and black army boots and his head and shoulders are deeply tanned, and he’s sporting wrap-around mirror shades. Hanging from a thick leather belt is a curving scabbard about a foot long. The hilt of the knife is non-descript but apparently the handle to a Gurkha with a blade somewhere between the length of a bayonet and a short machete. His three dogs sat out front of the shop and looked in through the plate glass doors to wait.

“Shadow,” I said, resisting the temptation to make a crack at his get-up

“Jackie Boy,” he smiled, pushing the shades up to uncover emerald eyes that twinkled with mischief. He gave my hand a respectably firm shake.

“Just couldn’t stay away from the fire,” I comment, turning back to my work. Trouble seemed to cling to Shadow like country ticks to a city dog, and he clearly liked the attention, one step ahead of the jailer-man and on the rip curl of the zeitgeist. That’s how I imagined him doing the math on it.

“Don’t let on to no one I’m back in town,” he said, tapping the keyboard to bring the screen up.“Just couldn’t stay away from the fire,” I comment, turning back to my work. Trouble seemed to cling to Shadow like country ticks to a city dog, and he clearly liked the attention, one step ahead of the jailer-man and on the rip curl of the zeitgeist. That’s how I imagined him doing the math on it.

“Your secret’s safe with me,” I promised. “I doubt anybody noticed you tromping down Main Street in that skirt and army boots,” I said. “With that pig sticker slapping your thigh.”

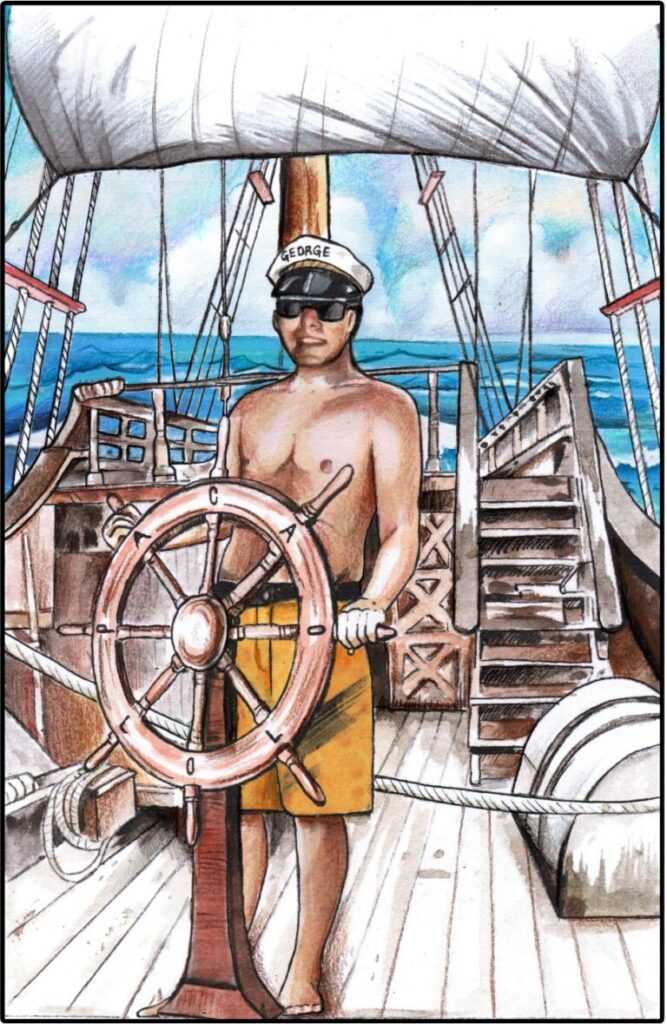

“Sikhs and fakirs got their turbans,” he said, “and A-Rab Islamists got their white robes. Me I been up in the Talamancas apprenticing under a Bribri shaman, and we got our own standards in couture.”“Your secret’s safe with me,” I promised. “I doubt anybody noticed you tromping down Main Street in that skirt and army boots,” I said. “With that pig sticker slapping your thigh.”

“Well, you ain’t missed much,” I told him. “Town will be glad to see you back, something to flap their gums about; been kind of slow around here since you skipped town.”

“I didn’t skip town, Stone, and I won’t be around long enough to keep small minds entertained. I’m here to collect my shit and head back up into the mountains with my dogs.”

“I’m going to be awful sorry to lose a paying customer, Shadow. You going up to take the iboga cure or something?”

“Yeah right, take the cure, like I’m some kind of junkie . . . I’ll be setting up an institute, if you must know, up in the headwaters of the Telire, on the Atlantic side of the divide.”

“An institute . . . wow that sounds like a big deal, Shadow.”

“An institute . . . wow that sounds like a big deal, Shadow.”

“You don’t have to patronize me, Stone, now just show me how I get onto my Hotmail.”

I think even a special forces commando washout would probably have the situational awareness to have detected the swarm of Guardia that crowded the door and peered into the plate glass above the three dogs from beneath mitts held up to deflect the sun’s glare. For my part, I certainly saw them. I look back on it and wonder if in that split second if somehow it was not a kind of a betrayal to not warn Shadow, since clearly, they were gathered in his honor. Course by warning a retired Special Forces Commando about the scrum of cops about to take his ass down in my shop it might possibly have led to the destruction of half my computers in the resulting melee; perhaps subliminally I did the math and figured it best to not cue him in if he was so distracted by his Hotmail that he didn’t realize the world of dookie about to rain down on him.

Corporal Tejeda was the tallest man on the force and was nearly as big around as he was tall. Yet despite his enormity, he moved like a jaguarondi and slipped right up on old Shadow like lightning falling through a cloudless day and before the sarong-ed former commando witch-doctor wannabe got wise, had reached down and pulled the blade out from the scabbard and tossed it across the floor where it skittered beneath the bookshelf. Shadow jumped to his feet to whorl around and I pushed away from the wall to send my office chair rolling across the tile floor and back out of harm’s way and the three officers took Shadow down faster than the collapse of American prestige following its invasion of Iraq and had his head pressed against the floor in no time flat, the big corporal with a knee in the small of Shadow’s back and his wrists wrestled up behind him and pushed upward till he got him a little Special Forces yelp out of the floored shaman-in-waiting, despite his five hundred thirty-two confirmed kills. Officer Silpancho, the one they called Gato Calvón, clicked the bracelets on, and the officers let up a bit and the tension evaporated. It had all gone down quite a bit easier than they had expected, and they eased the foreigner gently to his feet, respectfully now that the danger had passed, and the third officer, a recent rotation in, got down on his hands and knees to reach under the book shelf and fish out the pig sticker. The corporal gestured toward the door to allow the captive to lead the way of his own accord.

With his composure somewhat restored, Shadow looked over at me. “Get George,” he said. “Get George down here; he’ll get this settled.”

George and I had mostly kept to opposite sides of the street since my return last year. Four years ago, George had been part of the posse that had finally caught my old man and beat him and hog-tied him and turned him over bruised and bloodied to the same Lieutenant Silva that was now standing outside the shop to take charge of Shadow’s procession down the half block separating my Internet Café from the police station. That same Lieutenant back then had ordered Pops cut loose on the spot and apologized for his rough treatment and arrested his five captors and made them spend the night in his dirt-floored jail cell and sprung for drinks at the Paraiso for Dad and then proceeded to actually frog-march the vigilante squad down to the pier the next morning as if he was actually taking them across the water to Golfito to arraign them on charges of kidnapping and assault. He cut them loose at the last minute, but not before scaring the living bejesus out of the four gringos in the group. George was the only Tico in that crowd, the only one that actually knew they’d done wrong, that you can’t take the law into your hands in this country, even if it was with Scary Jerry, a mad man bent on larceny, vandalism, trouble-making, and general mayhem. I didn’t carry much of a grudge; truth was I could hardly blame any of them after what Dad had put them all through, though nobody really gets in life what they don’t mostly deserve. Still, George and Pops had been close before that, and me and George also, and in all this time he had never approached me to talk about it or apologize a little bit and so we still at that time kept mostly to opposite sides of the street. It wouldn’t be much longer we’d have to keep up appearances. George was in the advanced stages according to the town’s rumor mill and was certain to kick off pretty soon. Shadow had never done me any favors, and I didn’t make any plans to be messenger boy to the great white shaman-in-waiting. The way this town worked, word would reach George soon enough if it hadn’t already.his composure somewhat restored, Shadow looked over at me. “Get George,” he said. “Get George down here; he’ll get this settled.”

After Sylvia came back and I filled her in on the excitement she’d missed, I threw my head in the direction of the Delegación to let her know what I was headed out to do and stepped out into the afternoon sun to mosey on down the street where Shadow’s three dogs now waited patiently in front of the station house.

I stood around outside in the lengthening afternoon as the Sargent made hieroglyphic marks in his famous log book and ignored me as a breeze kicked up to set the canopy of the trees surrounding the soccer field in play. After the requisite time had passed without me becoming visibly impatient, the Sargent turned his ugly mug up in my direction to settle a quizzical glance upon me, my cue to finally state my business.

The Ticos had their own nickname for the man that we acknowledged as Shadow. They called him Zanate, which is slang for ‘mongrel.’ You might think it was because of the three mutts that followed him around that now sat patiently a few feet from us, or you might figure it was an unkind reference to the speculated nature of the man himself. In either case, the informal nickname worked pretty well for its double entendre, much better in my estimation than the banal ‘Shadow,’ which truth be known I found sophomoric and a bit over the top.

“Zanate,” I said to the Sargent, tossing my head back toward the rear where I knew from a personal experience a few years back the cell was located. “What’s he done? What you got him locked up for? He wasn’t causing no harm in my shop. He was being peaceable.”

“He ain’t locked up, Don Chaco,” the Sargent replied. “Just asking him a few questions is all.”

“I’d like to see the Lieutenant, Sarge,” I said. “Can you be so good as to announce me?”

That was when George rode up and came to a slow roll out front and stepped across the frame of his bicycle and planted a flip flop into the gravel and swung the bike around and planted the wheels in the gutter and a pedal against the curb. He turned away from it toward us with no further attention and the bicycle stood there under a blistering afternoon sun and seemed to quiver in the sudden arrest of its motion as a pair of macaws squawked above and pulled up to light in the upper boughs of a sea-grape tree to take it all in.

I reciprocated the grave nod which George tossed my way, and he put his arms up on the counter and leaned across it to stare into the policeman’s eyes for a moment before speaking. “Sargent Esquivel, I am here to collect my friend, the one you call Zanate, who is back there. Now you run back and bring him out front or get the Lieutenant out here front and center right now, thank you.”

“Don Jorge,” the Sargent smiled.

“Don’t Don Jorge me,” George leaned across the counter to plant his index finger in the middle of the Sargent’s complicated log of scribbled nonsense. “You get your sheep-fucker’s ass out of that seat and back in front of your boss’s face and get him out here in this lobby in front of me in the next fifteen seconds or I will see you shipped off till further notice to pound the pavement in Limón for the remainder of your miserable two-bit career. You reading me, Sargent?”

There aren’t many places in the world where you can talk like that to a cop and get away with it, and Puerto Jimenez is not really one of those places. I took stock of my unwitting involvement in the Sargent’s humiliation and turned away, but not before it was too late. George was dead within two months, but the Sargent was scribbling incomprehensible log entries for four more years from that same post before he finally got transferred off to somewhere to never again return. And in those four years there was not a single time that his and my eyes met but that both of us did not recall the memory of little George strong-arming him with such humiliating finality, and I always knew that in a dark alley with no consequences and just a bit larger cojones than he likely swung, the Sargent would surely have shot me dead to free himself of the single witness to his bitch-slapping by a 40-kilogram terminally ill man that could not have had the strength to lift anything heavier than his bicycle but a force of will greater than the Sarge could have mustered at even the height of his youth and vigor years earlier. That may sound melodramatic and overstated, but that’s sure the way it always seemed to me, and I was not any too sad when one day the old Sarge was no longer in town, replaced by a friendly woman Sargent, with whom I have always been cordial and never failed to get along.

“Let me see what I can do,” the Sargent looked up into George’s steady black eyes.

“Whatever you got on him, it must be pretty good,” I said after the Sargent backed away to go tend to George’s bidding.

“You know I had to, Jackie,” George turned those bottomless orbs on me. “Your old man he was out of his mind, but I am not telling you nothing you do not already know.” He paused for effect, his eyes unwavering. “You knew first and before anybody else and could at least have sounded a warning, but you did not do it, Jack, and this is just the way that people without recourse respond to events outside their control. Again, I am saying nothing to you that you do not already know.”

He looked at me and smiled but his eyes focused through me into a great distance where he seemed to be watching hidden events unfold, nostalgic at bearing witness to a history and destiny that others were not similarly burdened to observe.“You know I had to, Jackie,” George turned those bottomless orbs on me. “Your old man he was out of his mind, but I am not telling you nothing you do not already know.” He paused for effect, his eyes unwavering. “You knew first and before anybody else and could at least have sounded a warning, but you did not do it, Jack, and this is just the way that people without recourse respond to events outside their control. Again, I am saying nothing to you that you do not already know.”

“Anyway, I pull all the punches on him. I pretend to strike him but I never did, not really. I yell and curse him for the sake of his coward tormentors that paid my wages . . .” George chuckled and for a moment a familiar twinkle displaced the empty blackness that dwelled in his eyes to briefly revisit the times of camaraderie before the insanity, before the betrayals, before the night’s descent and the fragmentation of our tight-knit little circle of happy drunks and carefree miscreants. The twinkle fizzled into a sly grin as sounds in the shadows down the hall of the precinct betrayed movement toward goals set into motion and the black emptiness resettled into his stare. “Still, Chaco, I am sorry for being part of the desperation of those pieces of shit. I want you to tell you father from me when you see him, I am sorry about that.”He looked at me and smiled but his eyes focused through me into a great distance where he seemed to be watching hidden events unfold, nostalgic at bearing witness to a history and destiny that others were not similarly burdened to observe.“You know I had to, Jackie,” George turned those bottomless orbs on me. “Your old man he was out of his mind, but I am not telling you nothing you do not already know.” He paused for effect, his eyes unwavering. “You knew first and before anybody else and could at least have sounded a warning, but you did not do it, Jack, and this is just the way that people without recourse respond to events outside their control. Again, I am saying nothing to you that you do not already know.”

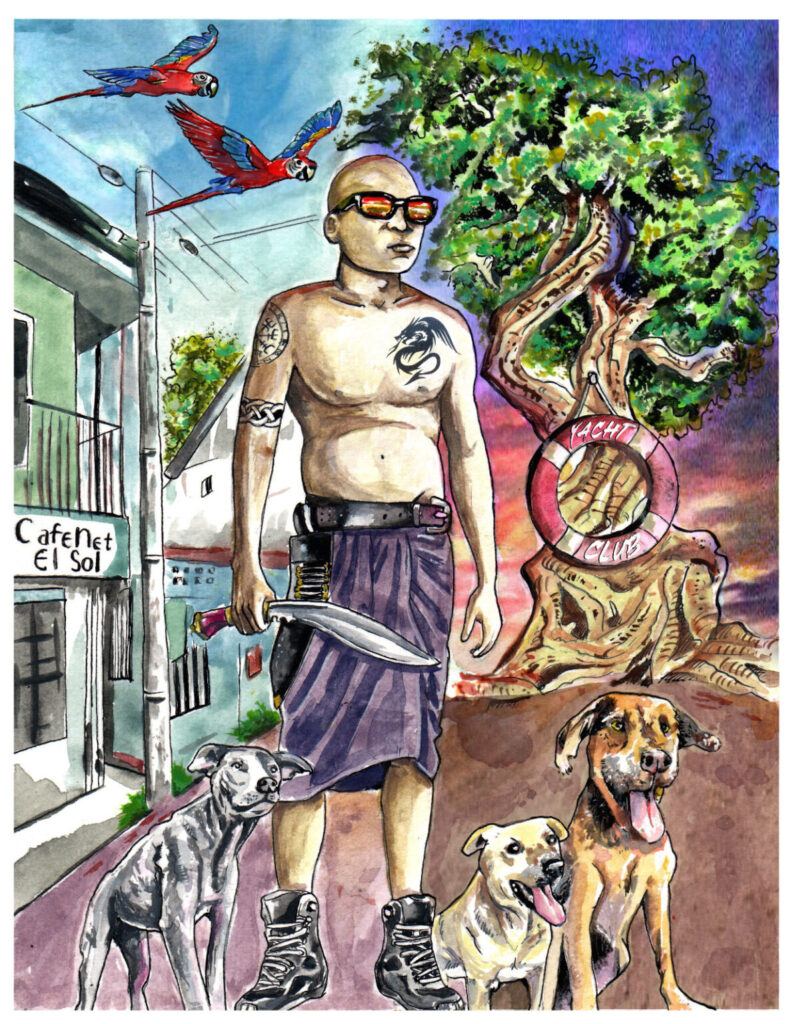

George was shirtless and wore surfer’s trunks. He had on his captain’s hat, and he doffed it and raked it across the belly that heretofore had always had a little roll of fat but that was now sunken inward only a bit less than the hollows of his cheeks and the black pits of his eye sockets. His captain’s hat was the real deal, unlike those adorning any head within fifty klicks of where the sun bore down on us that day and the mated-for-life macaws shucked sea-grape husks and chortled from the swaying fronds of tall trees as my brow cooled beneath the evaporation of sweat and the rustle of a hungry night rose on the afternoon breeze hooking down main street as passed-out drunks came around to sit up thirstily on soiled sidewalks beneath the chatter of town voices drifting up and down the tarmac in a musical passage through town. As the Lieutenant marched down the dark hallway toward the light with the man they called Zanate that we called Shadow whose real name was Randall Simon whose bare feet made a slapping sound in their passage across the tile floor beneath the whispered murmur of a struggling ceiling fan and the embarrassing rustle of his ridiculous skirt, George turned from me with a wink to steel himself against the more formidable Lieutenant. George called reefer pakalolo and said that Keith Moon’s drums were like the sound of his ass cheeks flapping from a good fart after eating Carolina Restaurant food but that Electric Light Orchestra was the Archangel Gabriel’s choir resonating through heaven’s refraction by the great fabled Hubble telescope. He liked to say that God was the anticipation of the biting taste of the next drink of Myer’s rum and the Devil the searing burn itself after a nice neat double and that mackerel smackers and lox lickers would never successfully ride herd over real men with no afterlife to look forward to and nothing to lose but shame and fear and that those that cared to dispute this could form a great long line to kiss the pimples of his indifferent ass. Though he had never taken a girl in the time I had known him, he did in the final stages, not so much, I think, to help him through with his dying, but I guess to sire a progeny, and it struck me how young and beautiful she was. George was in his mid-forties and nothing to look at even before the cancer struck and never had a pot to pee in, but I guess that mouth of his made the difference, and fifteen years later, his blood lives on in the little girl that was born from that union five months after he died.

“A gift for you,” the Lieutenant emerged from the shadows behind the bare-chested gringo to smile at George and declaim.

“We shall sustain the illusion together,” George scowled, summoning a curl of his lips into a semblance of a smile for form.

“Isn’t that what is expected of us?”

“Tell your friend to leave his toys in the toy-box.” The Lieutenant handed the shimmering kukri back over to the erstwhile ex-commando, who was pulling his boots back on and had the presence of mind to play his part with a bemused scowl, his smart talk mostly stowed. He shoved the weapon home into the scabbard and returned his attention to his boot laces.

“What if his toy box is the abdominal cavity of one of your officers, Lieutenant? Perhaps Sargent Esquivel here . . .” George turned to wink and finalize his humiliation of the scowling peace officer.

“I not kill police,” Shadow said dutifully in faltering Spanish, kneeling as his dogs swarmed him, leaping and licking. “I kill only bad people,” he scowled, pantomiming a stab that Apollo would two weeks later have ample room to mock and deride.

“Thanks for calling George in for me,” Shadow said to me. “And thanks, George, for coming down.”

“Don’t thank me,” George glared back; “go home; we’ll talk later.” Shadow lifted an eyebrow toward me and turned south as George found the pedal north and paused to stand on the brakes and whorl the bike around in the middle of the street to look at me.

“Your daddy here now, I go get drunk with him and laugh, forget my troubles,” he said, poking the captain’s hat so that it lay rakish on his head. “But you, Chaco, you are cut from different cloth, not so much good for me, you know what I mean?”

I figured I did and did not begrudge him the philosophical observation.

“I say I see you later, but you and me, we are atheist and me, I die soon, too soon, and I don’t think I see you again, and with any luck,” he licked his index finger and held it up in the air, “I probably will not have reason to ever think about you again neither. So, good-bye, Chaco.” He winked. “And you tell your father so long from old Georgie Boy.”

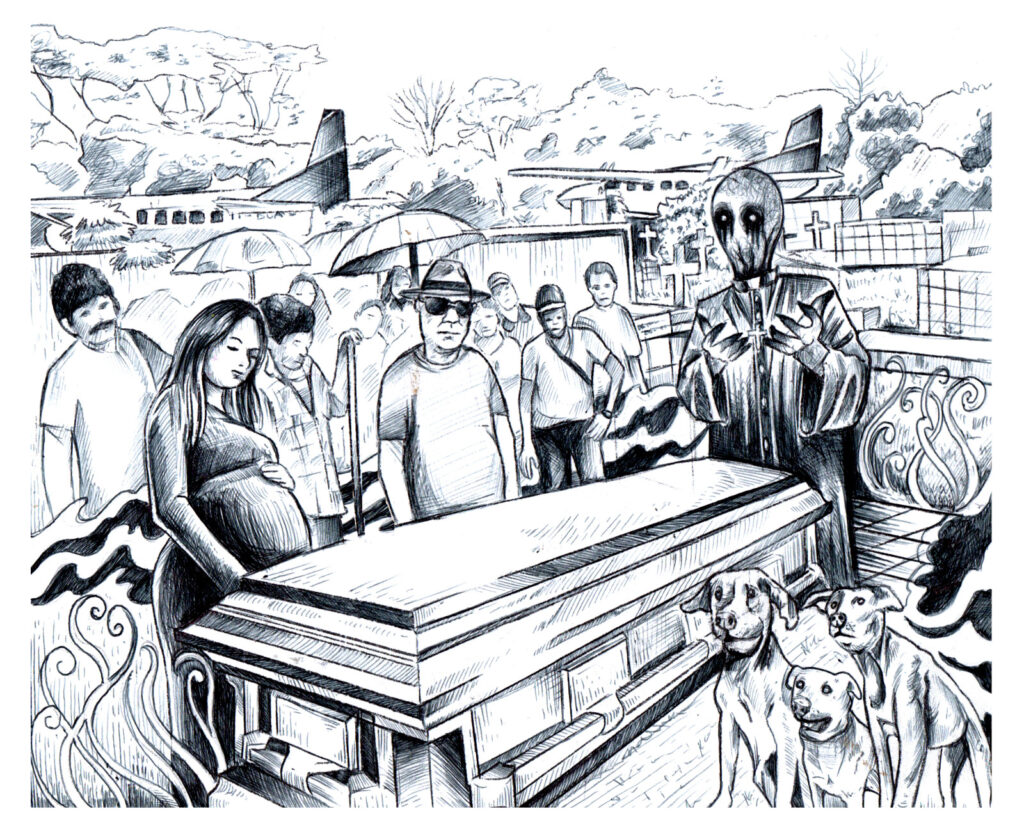

Counting myself and the priest there were eighteen of us in attendance for George’s funeral, which was held under a blazing late morning August sun. Ana Maria was already starting to show with the baby girl that would be born in early January and would be named at George’s dying insistence Mariluna Paz. I was perhaps the only one to roll my eyes at the Catholic service, which Ana Maria had declaimed was essential at a bare minimum for the soul of dear George to have the slightest chance of avoiding eternal damnation, and so the priest was there to guide us in our valley walk. As far as Shadow’s eternal fate, he was to have no such luck; no one appeared from abroad to claim his body and as Apollo settled into the first week of his six-month pre-trial preventive-prison term, one Randall Simon was cremated in the Alajuela morgue, his ashes added to the collective heap of the unclaimed, mourned only by three mongrels that finally broke ranks in paradise to seek their troubled fortunes on individual merits.

I splurged on a pint of Myer’s at the new liquor store in anticipation of my private little ceremony, and after the funereal crowd dispersed I strolled down the road beside the air strip and settled onto the roots of a coconut palm at the Yacht Club beach and had a little wake for not just George but for the good old Puerto Jimenez days of yore, now ground to dust under the rise of a paved runway, a huge supermarket, the town’s first Internet Café, the Crocodile Bay pier, and a zillion other trappings of modernity’s inevitable encroachment. I celebrated God and the Devil in the full cycle of the swallows that took me to the bottom of the bottle in George’s name and dropped the empty into the trash can of the Purruja Bar as I stumbled up the promenade toward the pier. The tide was half way in, and on fire, I scraped my belly on the bottom when I dove in to clear my head and quench the flames. Under water I looked at the scrapes on my abdomen and wished for sharks to catch the scent so I could tear their eyes out to hand feed the little barracudas darting about the shallows. But none came around, and I pulled myself out of the water and lay on the wood planks and fell asleep under a gentle sun as clouds built from the west to augur the afternoon’s rain.

I splurged on a pint of Myer’s at the new liquor store in anticipation of my private little ceremony, and after the funereal crowd dispersed I strolled down the road beside the air strip and settled onto the roots of a coconut palm at the Yacht Club beach and had a little wake for not just George but for the good old Puerto Jimenez days of yore, now ground to dust under the rise of a paved runway, a huge supermarket, the town’s first Internet Café, the Crocodile Bay pier, and a zillion other trappings of modernity’s inevitable encroachment. I celebrated God and the Devil in the full cycle of the swallows that took me to the bottom of the bottle in George’s name and dropped the empty into the trash can of the Purruja Bar as I stumbled up the promenade toward the pier. The tide was half way in, and on fire, I scraped my belly on the bottom when I dove in to clear my head and quench the flames. Under water I looked at the scrapes on my abdomen and wished for sharks to catch the scent so I could tear their eyes out to hand feed the little barracudas darting about the shallows. But none came around, and I pulled myself out of the water and lay on the wood planks and fell asleep under a gentle sun as clouds built from the west to augur the afternoon’s rain.