|

Jerome David Kahler In memoriam

July 20, 2014 |

|

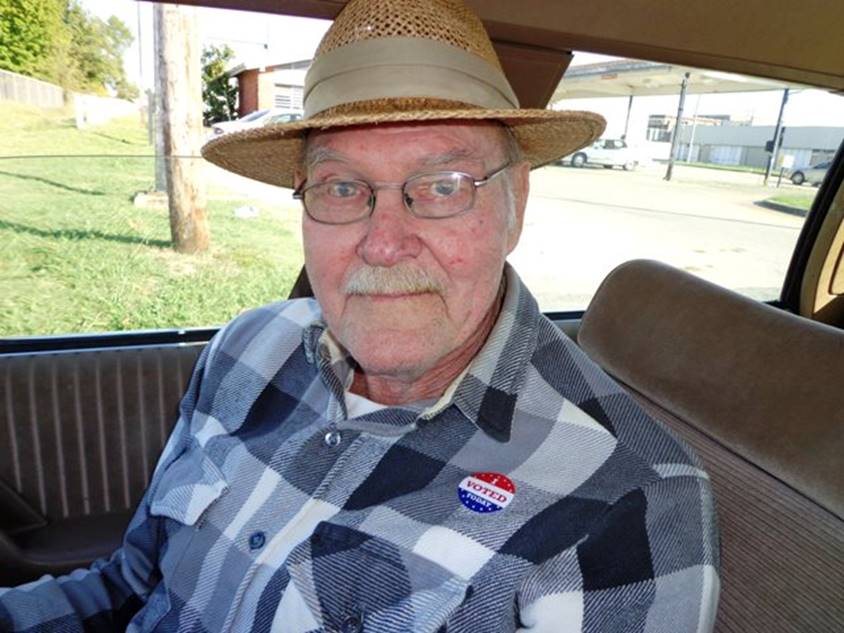

Today, my father, Jerome David Kahler, né Jerome David Collar, took his final breath and embarked on his fabled solution of the Great Mystery. Diagnosed with leukemia in the year 2000, a sufferer of bipolar syndrome perhaps all his life but demonstrably since his thirties, a lifelong heavy smoker and no stranger to drink, that he exceeded the average life expectancy and reached his 79th year intact and vital is nothing short of miraculous. Four weeks ago Dad was vivacious and active, on the verge of remodeling his Brody Bend home—the latest incarnation of my Fortress of Solitude—freshly back from his yearly sojourn to his nephew Russ Collar’s annual Rendezvous in northern California, when he was laid suddenly low with the recurring stomach problem that first manifested as an ulcer in 1967 in British Columbia and has since periodically haunted him with flare-ups that have not required hospitalization or medical treatment through the years. He uncharacteristically called for an ambulance from his BrodeyBend redoubt the night of June 26th—apparently realizing something was drastically wrong with this particular bout—and doctors discovered a gastric rupture the size of a silver dollar requiring immediate emergency surgery. Despite surgical intervention and aggressive and high-quality medical care, his body was unable to fight off the systemic infection that this rupture caused. The medical details are superfluous, tedious, and the epitome of TMI; the bottom line is that despite all the other lurking genies more likely to bring him face to face with the Great Mystery, what finally brokered the introduction was out of the blue and on the medical scale, arguably banal. He never regained real consciousness following surgery; after three weeks in intensive care, here I am at this momentous juncture, eulogizing a lion that paraded the planet too often in the skin of a wolf.

With the July world outside of my Little Rock window so green and hopeful, birds chirping, children still gleefully removed from school’s resumption, the evening insects conducting a symphony that great composers throughout history have emulated but never replicated, it is impossible to stanch the hope for my own future and that of kith and kin here in the full thick of this thing called life. I recoil in horror at a projection of the future, specifically my near and mid-term aspirations, with the sudden paralysis of my father’s absence from its excitement, from his sharing the elation of turning ideas into deeds, from the awful realization that he will not be there to shrug his shoulders with me over ambitions beyond my momentary reach. But the superego is there to the rescue, rushing in to defend these aspirations against the guilt that rises in Dad’s passing, as he would want nothing more than for his loved ones to persevere and aspire and dream and strive and overcome and to mock adversity as the plaything and modeling clay beneath the indomitable sculptor that is human will.

Last week a Costa Rican colleague of mine, a subcontractor that drives a truck and has delivered imported solar panels and batteries and water filtration equipment for me for years, died behind the wheel on the job in a crash on the stretch of the PanamericanHighway between Paso Robles and Palmar Norte. He was in his mid-thirties, handsome, fit, hard-working, honest, widely admired and respected. His death is a terrible, woeful tragedy. My father’s death is nature’s rational fulfillment of its awful wonderful cycle, a natural consequence of life, an antithesis of tragedy, arguably its own celebration of life’s fullest and final culmination.

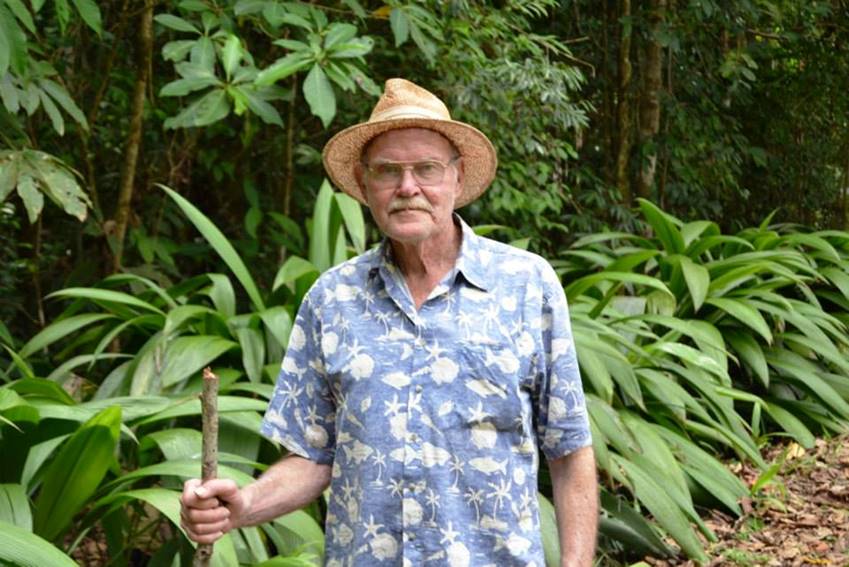

Some might argue that tragedy courted Dad not in death but in life from the recurring cataclysm of manic depression and its succession of objectively measurable abysmal lows and his relativistic measure of transcendental, even oracular, highs. Dad has seen the inside of more jail and prison cells in his time on this planet than any hardened criminal can be expected even in outlandish exaggeration to ever boast. Dad’s stints in mental institutions and funny farms and self-medicating exile to the wilds of the Ozark Mountains and jungle redoubts in Costa Rica, Mexico, and Canada are legion in our family repository of the legends that he birthed and lived and burned and resurrected time and time again across a lifetime that he stretched beyond any reasonable bargain with the gods and devils arrayed within him. Despite the very many momentary human adversaries that arose in different stages of his life over his prodigious range of misadventures, on his death bed he was unable to count a single enemy and from his generosity of spirit and fundamental kindness is widely loved and admired across multiple continents and the litany of decades that he can smile in the face of the Great Mystery at having fully and indefatigably lived.

I learned thirty years ago that Dad’s unfettered wolf was oil to my steady-state water and that I could not be around him when he went manic, that we were fundamentally incompatible when he let his wild thing off the leash to roam around the country-side. Its voracious curiosity and untiring ferocity were a torch that burned so brightly that I knew would consume me in its conflagration. Others were less unforgiving of the wolf’s prowl and some even found in its piercing eyes and unquenchable strength bizarre forms of empowerment and inspiration. Karl explored these themes extensively in his recently completed but as yet unpublished biography, Manic Dawn: The Strange Adventures of a Mad Father and a Loyal Son, and it would be presumptuous beside this scholarly and well-researched tome to reach even modest conclusions about the inseparability of Dad’s life and times from the mental illness that both ravaged and elevated him as it has to many throughout history and continues to do in our contemporary world.

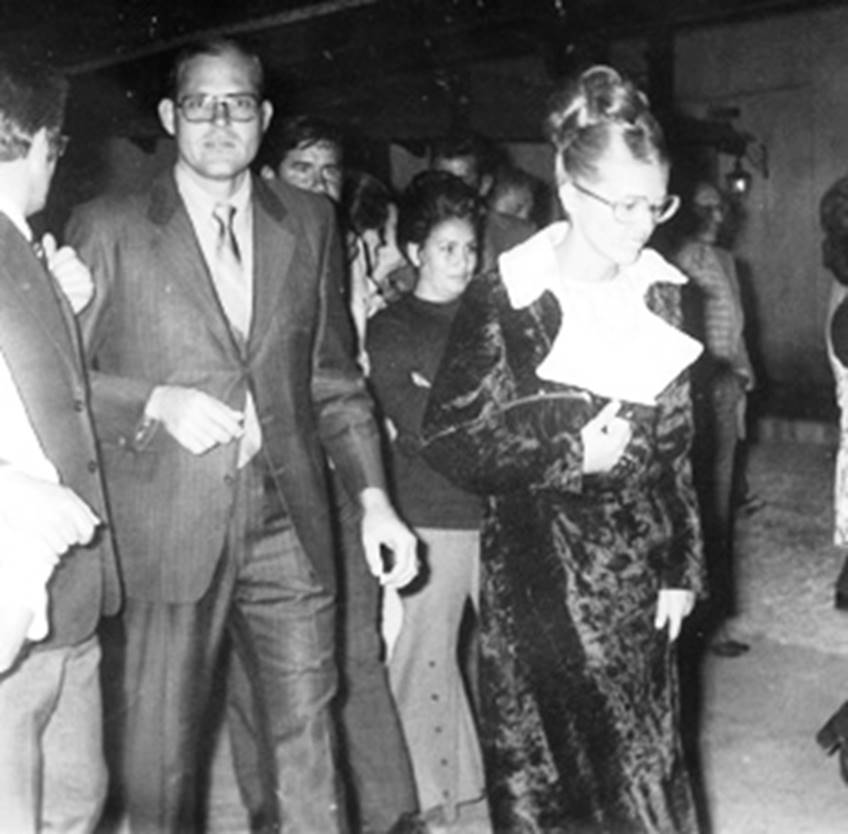

Dad was a native of Joiner, Arkansas, a graduate of Little Rocks’ notorious Central High School, a veteran of the US Navy, and a Yellow-Dog Democrat. He graduated with from Teacher’s College in Conway, now the University of Central Arkansas, and did graduate studies in bacteriology at the University of Arkansas and mycology at the University of British Columbia before closing out his academic career with a Doctorate in Education from the University of Arkansas in 1971. Years ago I happened upon my parents’ marriage certificate to discover that I was a little bun in the oven at the time they drove from Fayetteville’s Ivory Towers to, of all places, Tahlequah, Oklahoma, for a civil ceremony in 1960. Though he tried his hand briefly at life insurance sales—which he fondly recalled with revulsion—and did a stint as a bacteriologist with the Pine Bluff Arsenal in the presumptive furtherance of American military supremacy under the questionable aegis of biological weaponry, he hewed to a genetic calling in education and followed the footsteps of his father and mother as first a teacher and later as Principal and Superintendent of Schools, a career that took our family all across the western hemisphere from a gritty Hispanic southern California district in Orosi, California, to a one room school-house in Bigfoot’s backyard in the Marble Mountains hamlet of Somes Bar, California, to more exotic destinations: Anaco, Venezuela, Stewart British Columbia, Durango and Torreon, Mexico, Kodiak, Alaska, hibernating in safe and brief down-and-dirty tenures in the Arkansas school districts of Viola, Lonoke, and Leachville, before his educational swan’s song in Cochabamba, Bolivia, where I graduated from High School.

It never occurred to Karl and me that Dad and Mom had any career ambitions other than teaching, having lived that existence for as long as we could remember. We also did not recognize that our itinerant life-style of bouncing around year to year was somehow anything other than ordinary and normal. So, when Dad resigned from the Cochabamba Cooperative School at the very height of his protean career, little might we have imagined that he would never work again, indeed that he would never even seek to work again, and that a wolf mostly suppressed throughout the nurturing years would now be turned loose onto an unsuspecting family and world to gallivant about in unrestrained mischief and derring-do.

The next two decades as Karl and I came into our own and completed our own college careers, married, made babies, and took jobs, Dad bounced from jail to jail to prison to mental institution and drove his mother to distraction at the stunning and wholesale reversal of his life’s direction. It culminated after a year of preventive prison in Costa Rica’s notorious Reforma with a long federal prison sentence under mandated sentencing during the War on Drugs over 27 juvenile pot plants in the Ozark National Forest and some additional hard time for walking away from a Country Club federal prison in Texarkana.

His mother, our family’s towering matriarch, Noma Collar, died at 91, months before his parole, and his beloved younger brother, James Collar, died of leukemia two years afterward in the Brodey Bend home that they set up together after Dad’s half-way-house period on a bank overlooking a slough of the mighty Arkansas River. The day of Jim’s death, Dad was on a trip with Lynn Bulloch, the woman that stood beside him through the hard decades—his fiancée of thirty years—that mourns him beside the rest of us on Dad’s doleful reckoning today with the Great Mystery. Though my grandmother’s death, like Dad’s, was no tragedy but simply a hated knick point in life’s majestic cycles, Uncle Jim was taken well before his time in the brimming springtime of Dad’s final chapter and left Dad and the rest of our family desolate in the cruel and truly tragic untimeliness of his death.

Perhaps everybody does not need a Fortress of Solitude, but I certainly always have. In the geographical shiftlessness that marked my childhood and adolescence, our grandparents’ homes in Norphlet and Little Rock were always beacons of permanence and safe bases that Karl and I returned to fondly each summer to derive a subliminal grounding—I think in retrospect—that less mobile people perhaps get from a constancy and familiarity that we never knew. In my college years, my maternal grandparents’ retirement home in Heber Springs was my Fortress of Solitude, a base to which I could escape from school and nurture a security and stability that I missed long after they died in quick succession in the early nineties. For a while I thought that my mother’s Sparkman home with Husband Number Four, Aubrey Jones, a country boy whom I came to admire and love, would grow into that mold and take over as that place where I might gather my strengths to punctuate my continued wandering about the world. But they divorced the year I moved to Costa Rica, and that possibility crumbled into dust as I reluctantly helped her move to an apartment in Camden, the settled world now fallen newly apart as Dad pulled his final months in the pen. Then, like a phoenix rising from the ashes of loss, Dad’s Brodey Bend rose to claim that void, and over the past fourteen years, I have relished and cherished my retreats to hang with Dad at the river.

In the Fall we watched white pelicans herd shad in the slough and in the Winter split oak to keep the wood stove fed. In the Spring there were crappie to catch in the river and bass in the nearby pond; in the Summer we painted and roofed and did carpentry and imbibed gaily the smell of freshly mown grass. There was the horse that thought he was a cow in the pasture out back that Dad would spoil with carrots, a horse that on a doleful final homecoming last week I imagined confused about his identity all over again now that the cattle have been moved off and he is left alone in a field well beyond his alimentary needs. The River Rats convened nightly in the summers for drinking and yarns in folding chairs before impromptu bonfires and party barges up and down the river and kids running around being happy, dogs nipping at their heels and rolling in the grass till the mosquitoes would drive us inside. There was Internet and nightly news and meals that I would cook. Dad was indomitable in gin rummy, and my cumulative debt to him at our penny-a-point games is somewhere north of a thousand dollars. He savaged partners and opponents alike in online bridge, a game in which luck is a chip on the shoulder of less talented players, and I laid low there flat broke in 2004 for three Autumn months from a particularly hard time with my Costa Rican incarnation, a crux point at which I was set to sell off everything and move to the next unknown thing but instead found in my pennilessness at the Brodey Bend Fortress and Dad’s irrepressible inspiration the reasons and resolve to double down on Costa Rica. We took off on the great Get-Out-the-Vote Road Trip to California and back that October, and Dad was disconsolate when we awakened the day after the election in reddest-of-red Idaho to discover Bush had been re-elected, this time without the assistance of the Supreme Court. Dad did not utter a word the full three hours into even redder Salt Lake City, and was not out of his funk by crimson Cheyenne, and we raced on through the afternoon through then pink-o Colorado and finally holed up in a hotel in carmine Kansas about five in the morning to limp back to the River the next day, from one red state to another to another to another to finally reach the tiny blue enclave of Jefferson County in our still sadly red State of Arkansas, and we assuaged our political funk back on the River over a case of beer and grilled hamburgers. I got a break on an Osa Water Works contract by email pluck—Google engineering, Dad liked to joke—that allowed me to return to paradise under the promise a few thousand dollars of earnings and the renewal of faith engendered by my restorative retreat at Dad’s Brodey Bend Fortress of Solitude. I flew back to my chosen home in Costa Rica to turn my own fortunes around and have not in the ten years hence had to once look back. For that and many things, Dad, thank you.

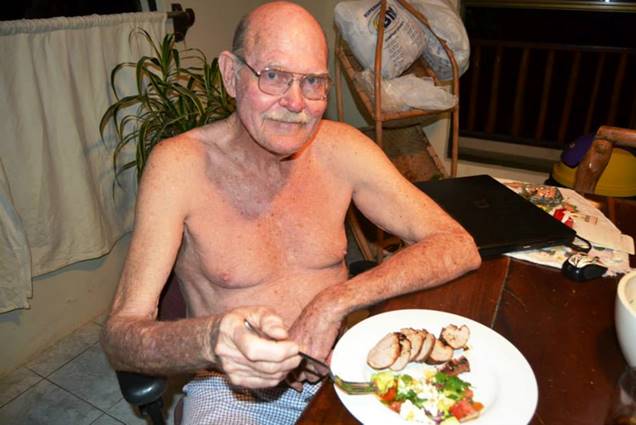

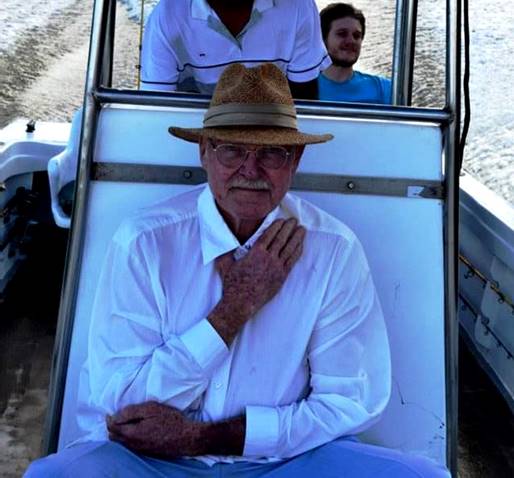

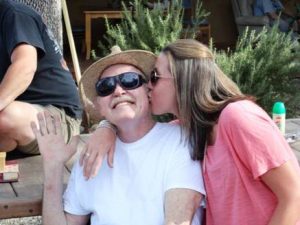

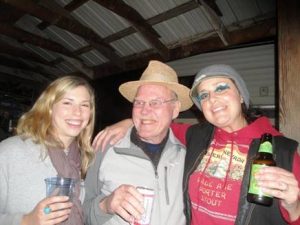

It is not always evident when you are in the middle of good times to recognize them as such and revel in them and celebrate them. Yet, I look back on the last ten years and see that, improbably, I did recognize these good years for what they were and luckily was able to relish the juice that I sucked from the marrow in the two to three annual peregrinations I have faithfully made since to spend time with my father, whose awful totem of the wolf unleashed segued in the autumn of his life into a purring lion of infinite generosity and sagacity. He, too, lived on the razor’s edge of happiness’s realization and made annual pilgrimages to Costa Rica, coinciding several times with visits from one or both of my sons as well as from Karl and his son, Jordan, plus one famously happy reunion at Brodey Bend that included his grandchildren, Nathan, Jordan, Orpheus, and Aladdin, as well as Russ. No treasure on Earth can possibly surpass that of happy memories of times where the happiness is recognized in its moment and duly embraced.

In the end there is family and friends. There is no beginning or middle that compares, and Dad’s patriarchy over our scattered clan has remained a beacon of benevolence and generosity to which Dad’s successive two generations to date will always be able to trace an indelible and ineradicable debt. With the lion’s passage, Karl and I become family elders, the old folks, the repositories of purported wisdom, restraint, and ambition to which our age and station now imbue us by default if not yet fully by native or accrued talents.

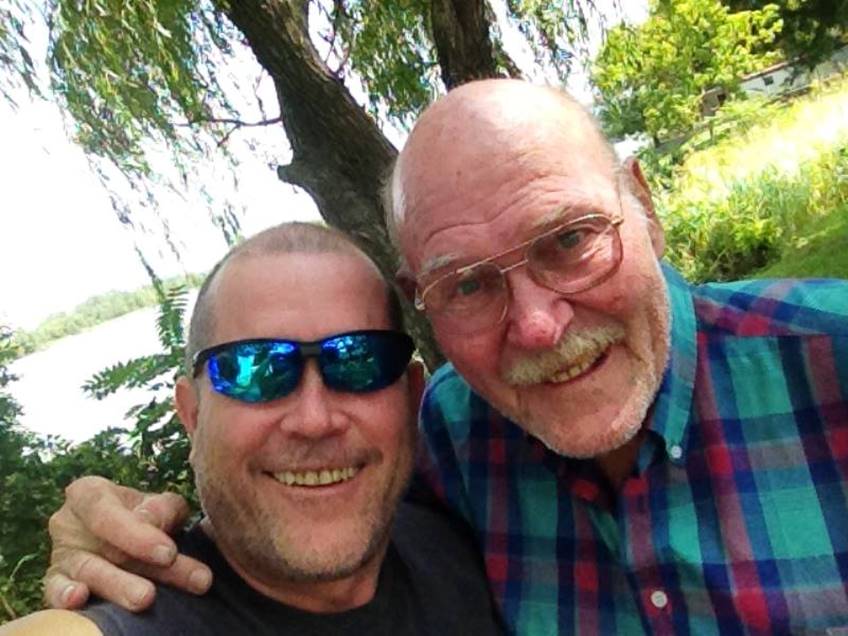

2013: Leafy Gables family portrait: Nathan, Aladdin, Karl, Dad, Jordan, Orpheus, me

For everything that I am and all that I am capable I will forever be in debt and grateful to the incomparable father that through his example of what to do and not do and how to make the best of both deeds and misdeeds, helped me to forge who I am.

Pops, I can’t imagine a day in what remains of my life in which your beacon will not disperse what shadows intrude and illumine all that is lovely and succulent about this amazing life that from your example and deeds I am able to happily and eagerly embrace and treasure. I love you as time does its heroes, as patriots their liberty, as a suckling child its mother’s breast, as destiny does its stone foundations.

I do not mourn your death but celebrate your life, and I thank you for the brush strokes with which you have brought beauty, adornment, and felicity to this wonderful wholeness of this incandescent little thing we call life.