El Lugar Añejo

“It’s your lucky day, Hank.”

Hal Bones was out of Miami, managing partner at Central American Realty. The contents of his cleared-out desk on its surface, the files cleared, only knick-knacks to go to rid vestiges of himself from the office, Henry Morland frowned.

“Everybody makes their own luck, old pal.”

“Fraid you’d cut out early today.”

“If you’d really thought it you’d a tried me on my cell first.”

“Busted. I knew you’d be there.”

“I won’t miss it much. What’s up, Bones?”

“I need you, Hank. I got these Italians. It’s a Belize gig, you see, a ten star resort on 500 hectares.”

“I have hung up my guns, Bones.”

“I told them on your way out the door they’d have to make an offer you can’t refuse.”

“Great first independent job for Alvaro.”

“He ain’t the best, Hank.”

“He is now.”

“Twenty grand, Hank, plus expenses of course, first class airfare, helicopter transfers; you should have a look.”

“It’s not money, bones; I’m retired.”

“It’s a quarter to six there, Hank. You ain’t retired yet.”

“I got my Santiago tickets, Bones. I am matching the hatch as we speak in a Patagonian dawn and battling brown trout. It’s scratchin’ the noggin and rubbin’ the belly from here on out.”

“We’ll get your change fees, no problem. Patagonia is not going anywhere. Listen, I’ll throw in another ten large from my pocket if I land this sale.”

Morland paused. At length he said, “I don’t much care for Belize.”

“Be a pal, Hank. For old time’s sake . . .”

***

San Pedro Sula had the highest murder rate of any city in Honduras, and Honduras had the highest murder rate of any country in the world not actively engaged in a war. His layover in this most murderous city on the planet was two hours. Sixteen years earlier—on a dam engineering assignment—he had gotten the ransom call on his cell, Derek’s voice grim and small over the static in the line, Katie beside him in the back seat before the phone was snatched away. El Bordo Maras had bribed their way past gated security to whisk them away to the slum. Bechtel had sprung for the ransom, but he had been the bagman, walking in expecting the hail of bullets that would have been the only honorable way out of getting his kids killed over another job assignment in a sketchy place. The ordeal had precipitated an awkward divorce from Sarah and a few hard years getting over it, but Derek was two years now with Exxon in his own career and Katie in her final year at the Peabody Conservatory for voice. For her part, Sarah was unhappily remarried to a former ex-pat she was able to finally control, fattening in his retirement on port and foie gras in Sedona, so things could certainly be worse.

He could have connected through San Salvador to revisit the country he had driven through in ‘91, past the then mortar-cratered landscape, pock-marked walls, and bullet-riddled plate glass of urban towers, but it would have added a few more hours to his trip and denied him reliving that trip to the barrio, the glazed eyes of the inked gangster that took the money, the fevered emergence from a battered doorway of his two children, Derek sprinting across the square toward him with his sister’s hand melded white-knuckled in his own, the Range Rover bristling with firepower behind him, squawks on the handhelds, the street emptied of beggars, lottery vendors, and nickel-bag dealers, itinerant shopkeepers huddled in the dark behind the roll-doors slammed to the grimy sidewalk of an unforgiving street . . .

Drinks were still free, at least on Taca, and the steward poured him a stiff double Stoli in a highball glass brimming with ice and handed him a can of bloody mary mix before the commercial class filed past to take their seats. The old liver had held up well through the years, and he toasted its health. He was still in pretty good shape, despite the memory lapses from too many knocks on the head and the lifelong struggle with his knee. He might bow to his doctor man on knee surgery, get it all tied up and new again inside, make it a retirement present to himself to face those trout streams with a longer lasting gait. But it wasn’t so bad if he didn’t push it too hard, and at sixty-two, it might be late in the game for another round under the knife.

From the ground, southeastern Guatemala was southern Colorado, big mountains with evergreen forests, semi-arid, broad valley bottoms with clear water, tall cottonwood-like trees lining the rivers upstream of where Colorado ran out and Honduras began in the lowland jungle and then mangroves nearing the Mosquito Coast. But from thirty thousand feet the feel was missing, and it was like the rest of the isthmus but for Costa Rica and other parts of Guatemala from the air. It was probably just bias after ten good years, and after a few months in Argentina and Chile, he would buy a place in Atenas or Santa Ana and work on a memoir. Guat City came up fast, and he gazed upon its sere urbanity sprawled across the breadth of the basin. The city, home to as many people as the entire nation of Costa Rica, radiated outward from the small concrete canyon land of downtown towers to roll across the rich rolling terrace and then up the flanks of all the enclosing mountains. Deeply incised channels marked streams polluted beyond any memory of a natural state by decades of garbage, sewage, and hazardous waste, more recently by the rotting remains of the footmen of this expanding front of the hemisphere’s cartel wars.

The western sky was orange, the sun pink as it pierced a blend of industrial haze and volcanic ash from smoking Pacaya off to the northwest. He had dipped his estik into red-hot lava near its summit just a few years ago, playing Cassanova to the daddy-complex daughter of a client. He weaved the two-to-one club ground rules well enough, armed with a pocketful of Viagra, and perhaps he could still swing it six years on. He let the lifted shade’s salmon dusk light his face as the Guat-bound trundled past and had another double before the Belize set trundled back in the other direction.

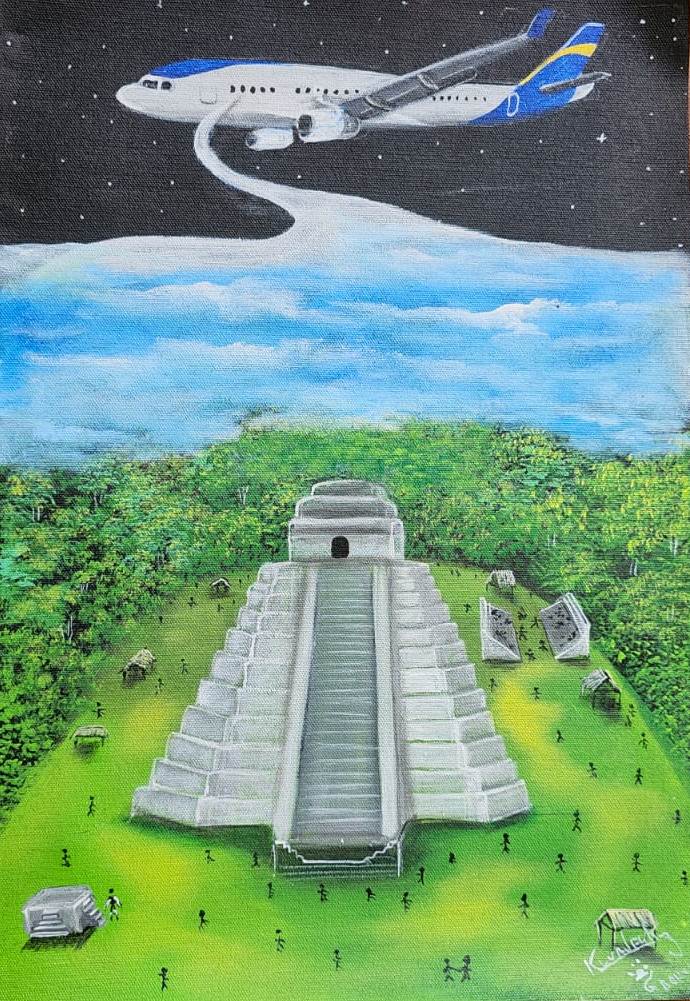

His knee recoiled crossing his legs after take-off. Buy knee brace had been on yesterday’s to-do list. But for the past few years, the to-do list was an action to remember, not a resource to remind, and in the middle-aged slip of neurons in an Alzheimer’s world, it had fallen by the wayside. The old one had been unredeemable following the Terraba swamp, and he had pitched it following his supposed swan’s song job. Sourcing a new one tomorrow would be its meddlesome delay, and in Belize City of all places. The vodka and the final band of crimson lace fading behind him jousted with one another over bragging rights in the constitution of his fine mood, and he pushed himself outside the craft to settle over the vast Petén limestone plateau that steeped below him in a vast unrecorded history. The subjects of Tikal walked and worked the land below as the Classic Age crashed against a wave of decadal-scale droughts, famine, and pestilence. Ceremonial slaughter proved insufficient to discourage the angry gods, despite the nobility’s efficiency at keeping the blood flowing. Wars and intrigue ground empire’s fall into an ugly slog of hardship and cruelty as labile city-state allegiances crumbled and the land’s bounty decayed. Old friends now came for your heart, old enemies for your head. The peasantry first, fleeing into the wilderness or dying, then the merchant and service class shocked at their fall in stature, unskilled in the banality of pure survival, coldly reaching finally for the priests and rulers themselves to tear them from towering sacristies and cast them in a pulp of broken bones and torn flesh to the forest floor worm below that would quietly restore itself to an original and higher order. As the plane’s attitude shifted to announce its descent in advance of the pilot’s voice, he projected himself above San Gabriel, the only town on the Belize mainland that he had ever considered with particular favor, its Mennonite enclave husbanding the fertile land, its Roaring River rushing through boulder-strewn rapids, the smell of curry and jerked meat wafting sleepily from brightly painted cottages on the Creole side of town. As the minutes moved forward and the craft descended further he looked out over the expanse of blackness and its smattering of lights and pulled the hurricane-ravaged scrub into his mind’s eye, its miles upon miles of bramble and underfoot muck, its lurking snakes and caimans, and its predatory wading birds poaching frogs and fish and the patient severity of their coiled articulated necks before the blinding strike of beaks so long and certain that no one with any imagination could deny their direct descendancy from dinosaurs.

The queue for customs and immigration, the veneer of patronage and prejudice in a disordered Belizean universe, the grime on the wall and dollops of spit on the mean grey floor tile, left Hank Morland sober as he migrated his Dockers across the tacky tarmac to stand inside the grimy customs house. The official was an obese young woman, and from the frown she affixed on his documents as she flipped through the visa pages you might think he was a Rowhingyan refugee from Burma or a Dominican hooker or something. He loosened up and smiled and got goofy. It was an old game. He had mastered it before she had been a warm glow in her mum’s thighs.

“Your business in Belize?” she looked up at him doubtfully.

He kept smiling. As circumspect as he remained to this curious excuse of a nation, he could not help but love its accents, from the pervasive kriol lingua franca to the British-tinged sing-song English of his momentary interrogator to the burbled Chinese English of its merchant class, from the tortured English of the mestizo Spanish-speakers of its northern savannah and western uplands to the boozy Windsorian affectation of upper-crusters with nowhere left to turn, their pearl a final stand in a decay the edges of which only regular doses of finely infused Bombay gin could nominally soften.

“Diving,” he replied. “Never done the Blue Hole. Maybe a little bonefishing, check out the ruins. You know,” he grinned. “The usual.”

She stared at him a bit and reached for the stamp and let gravity lower her meaty paw, enough to barely ink the page. She yawned and wrote in “30 days,” and returned his documents with a smile. “Welcome to Belize, Mister Morland.”

Señor Lopez was a middle-aged mestizo with a toothy grin and a hefty paunch. He sported a handle-bar moustache and two tall, muscled bodyguards with loose sports inside of which glints of steel winked and peeped. The limousine was frosty, and the sweat on his forehead evaporated coolly as his glasses fogged and he sank into the leather seat beside his contact. Morland declined the offer of a cocktail as the Bentley pulled into traffic, and his host clucked his disappointment.

“Richard,” López allowed as they slowed into a snarling medley of traffic cones, converging toward a distant hummocky surface of a single lane. “The hurricane industry did a brisk trade with us in 2010.”

“Few deaths, I understand,” Morland said.

“Officially,” snorted Lopez. “Unofficially, who knows? It was a direct hit, and the roots class is always loath to evacuate. Even hovels can be usurped if left untended. So, who knows, but for the sake of our tourism sector, Belmopan under-reports. Are you sure you won’t have a cocktail, Señor Morland?” Hank found his host’s face twisted into an entreaty. “I can assure you that the ice is clean.”

“Since you insist.” The car stopped and the AC steamed whitely from the vents. “I’ll have what you’re having.”

Mr. Lopez erupted in a smile that nearly burst the armored sides of their conveyance outward and hopped to and confectioned two double sloe gin fizzes and held out a half key lime shielded by a monogrammed cocktail napkin pinioned between his fingers so that Morland could squeeze his own. It was very good and as they inched their way out of the ink and into the greying of the city, he allowed that he might be persuaded to indulge a second one, an admission greeted with grave glee by his now chatty host.

***

Hank Morland’s distaste for Anderson Cooper was only slightly less than for the physician turned television personality Sanjay Gupta that CNN had kicked downstairs after the awful coverage of the Haitian earthquake a few years ago. But they were mother’s milk beside the contemptible Piers Morgan, and he allowed the flat screen to assault him by all three as he checked his emails in the decayed grandeur of his suite. The Caribbean air bum-rushed the room through the open doors of the balcony. Above the delightful pirate’s harbor outside, a resplendent crescent moon hung in a licentious night that spilled into his room and smelled of debauchery.

Katie was online, and he surfed the mind’s wave of the years, beginning with her pinched and cheesy emergence into a Tanzanian boudoir from a sweating, heaving, wide-eyed Sarah and a severe Shambaa midwife a head taller than he that stroked his wife’s brow and perineum with equal fervor. He cut to her toddler’s rein of terror as Zimbabwe edged toward Mugabe and celestial chords first broke chimerically through from her shrieks of glee in the stalking of iguanas and the mugging at larcenous courtyard baboons to grade-school and the pink and white tutus of Lausanne and her tom-boy’s slingshot of Coeur D’Alene and proud hoisting of the killed chucker that he had slowly baked with rosemary and wine and eaten with her alone with chilled mineral water to simulate champagne while Derek and Sarah had mac n cheese and leftovers to their night of life and death in Sula to prom night at San Jose’s Lincoln School and her wide-eyed date with his lavender tux and orchid corsage, the keys to his old man’s beamer trembling in his hands, to last year’s Manhattan rendezvous at Elaine’s, his baby blossomed into a full and whole woman, a twenty-two year old debutante as physically fulsome as she might ever be again, to tonight, all of her encapsulated impossibly into a tiny image on a computer screen with an orange dot beside her. He embraced her wholeness, arias swirling around him in the room, and released her to her June oyster world as room service knocked with his meal, and he bade the formal young man impossibly black inside his blinding white uniform into the room and took a contemplative sip of Chablis and found his head swinging toward the balcony and the chaotic night roiling outside as the television personalities extruded their vast egos into the pleasant space that enfolded him.

***

The target was two properties that shared a boundary along the Monkey River in the Mayan Mountain highlands. Their project was, naturally, to be no normal ecolodge, but a world-class destination with amenities on the par with Monaco’s finest but one melded with with the native environment, where affluent travelers could retreat to an environmental mecca with quetzals and jaguars competing for jaded gazes, where unrevealed Mayan antiquities might stoke the mystic passions of bored blue-haired dames, where nearby reefs, cenotes, and primeval jungle would afford their grown children with the necessary distractions from roulette wheels and Ferraris to stoke the fires of those for whom imagination had evolved into an actual commodity. Belize afforded a unique blend of security and savagery that allowed imagined danger and discreet excess to commingle into a singular whole, all shielded by an institutional permissivity that would allow guests of their target stratum to transcend for the week of their stay the oppressive banality of privilege. The investment group had passed over Costa Rica as too conventional, steered clear of Colombia as too dangerous, dismissed Mexico as too gaudy. Panama was, je ne c’est quoi, not right, Brazil too vast and permeable, Venezuela too volatile, Guatemala too violent, Ecuador too socialist, and Asia too pedestrian for their target market. Belize was just right in the impossible matrix of their curious criteria, and the target was the group’s leading choice of three alternatives culled from the beating of bushes by hungry scouts sent out on lead by the investment group.

“Your mission is to prove it out for us.” Marcello Tagliani stood with his back to Morland, his hands clasped behind him, and gazed out over the sea from inside the balcony doors of his own suite. He was a well-tanned handsome man in his early forties with immaculate hair and an expensive casual suit. He was polite and soft-spoken, yet appropriately stern for their first meeting, and he had turned his back on Morland to glance upon the sea back in the direction of his homeland in order to compile the vision appropriately for the contractor. “We expect to require at least 100 kilowatts in reasonable proximity to a building site of mythic proportions, with magnificent views, forested with old growth that we may selectively cull to achieve an architectural aesthetic required for our model.”

But he was like Morland himself, just a hired gun, and when he turned back with a cautious smile, he must have caught Morland’s amusement in an unguarded twinkle of an eye. The posturing and naiveté were the only thing world class so far, but there remained far more money than sense in what the world had become, and if it was there, he could sure ferret it out and prove it for them. The man’s shoulders fell slightly beneath his exhale, and the smile grew, and his sigh betrayed the inevitability of his professed convictions as perhaps a stretch. Hank felt the man’s perspiration beading in the small of his back and the uncomfortable cling of his silk shirt in this oppressive air so far from his domesticated and familiar Mediterranean.

“Any ruins on the properties?”

“Curious that you ask, yes, supposedly, but nothing major, nothing excavated. We have nothing on paper, just some rumors. The owners have said very little about it, leading us to think they are minor and not of great value to our project. But you can be sure we will play that end up in our marketing platform. The bridge to a lost civilization, and all that happy nonsense. It’s fundamental to our project.”

“What is it that you are not telling me?”

“Well,” Marcello replied, glancing down, “there is a slight inconvenience. The Bonair and Carranza families are not friendly with one another, so there is a bit of resistance in the logistics of the eventual deal—no concern to you there—but also, frankly, with the mechanics of your mission.”

“Neighbors will be neighbors,” Morland said. “Surely not a woman involved?”

“Isn’t there always one mixed up somewhere?” Tagliano chuckled. “Our main interest is along the river, of course, where the properties meet, so you will see how best to juggle the personalities to get you where you most need to be.”

“I’m sure if the money is right, these folks will all come around.”

“We are certain of it.”

“Anything else?”

The man opened a drawer of the dresser to withdrew a shoulder harness with a nickel-plated automatic holstered and handed it to Morland. “Just in case,” he said.

“Thanks, but nothing more dangerous in a tense environment than an armed consultant.”

The Italian frowned. “Are you sure? It is wild country. Many dangerous animals are about.”

“Mostly of the two-legged variety, I’ll bet. I’d just have it taken and used against me, or shoot myself in the foot. I’ll be fine with my own tools.”

***

A helicopter for field reconnaissance was a first, and he pulled rank inside the cockpit and had the pilot return to file a revised flight plan.

“You want me be changie black dog fuh monkey, mon?”

“Something like that.”

“You da one pay da mon, mon,” the pilot smiled.

Well, not really, but close enough.

They followed the coast south about a mile offshore and crossed the coast north of a town strafed by the elements. “Gales Point,” barked the captain through the headset. “Take it hard from Richard.” Ten minutes later they crossed a blacktop. “South Highway,” the pilot pointed. In another ten minutes they passed the headwaters of a stream that opened into a valley trending northeast. “Raspacula Branch,” Morland pointed out.

“Don’t know to tell sure,” Captain Marvin yelled.

“I tell you sure,” Morland barked. “Drains yonder about 20 miles downstream into the Roaring River at San Gabriel, where it flows into the Belize. See that ridge, Captain?” Morlock swung his arm to the southwest. Take us over there; let’s follow the ridgeline the rest of the way, and take us down a bit; I’d like to smell the roses.”

Morland snapped pictures and divided his attention between his handheld GPS, the Mayan Mountain ridgeline divide, the watersheds draining to the east, and the console instrumentation where the Bonair destination was flagged. When he made out the trace of the Monkey River he twirled his fingers in the air and Captain Marvin swung them around two passes around the river’s spring feed zone near the divide. He pointed toward a narrow shallow ridge on the Bonair side of the river where he expected his Italians’ Nirvana to lay if anywhere. The river gained well from the confluence of feeders, with plenty of flow. “There,” he pointed, “closer look, please.”

A series of rapids flowed through boulder throw in a modest gorge in what looked to be 10-20 cfs of flow and perhaps a hundred feet of overall drop, and the northern bank rose to the same Nirvana ridge that swelled into a gently sloping finger plateau all covered in primary but flat-looking, buildable. They swung to its northern slope, covered in advanced secondary with a good fifty years to it. Beyond, emerald green rice fields extended to the north and east in a vast flat as far as he could make out. The south side of the river was a riparian zone of younger secondary, perhaps thirty years—forest enough for city folk—and beyond was the rolling pastureland of the Carranza’s cattle operation. Downstream the secondary thinned, and the river terrace on the Bonair side alternated with copses of trees and dappled meadows giving to a flat plain, the Carranza side rolling foothills. He smiled at the pilot and moved his finger forward to not cut to their destination just yet but to follow the river downstream. A flock of cattle egrets started into the air and the herd of brahma cattle glanced up to monitor the helicopter’s unusual passage. A hint of pink in the wading birds just before they reached the highway betrayed them as roseate spoonbills, and he wondered if the snook made it this far inland. Morland moved his finger to the right in a circle to simulate a loop around the Carranza ranch, and they followed the highway for a while and then cut back to the north across rolling pastureland that gave way to forest and mountains ahead. He guided the bird across the hummocky surface near where they left the highway to get a feel for an access road in a pretty section of the ranch as an alternative to improvement of the existing Carranza access on the ugly southern end of their property. He imagined a bridge across the Monkey River above the rapids—or a tram perhaps—maybe even directly over the falls to stimulate the beautiful people’s imaginations. Yeah, his bosses—whoever they were—would like the idea of a tram. When they regained the feed zone at the northwest boundary, he motioned for Captain Marvin to sweep wide and follow the northern boundary of the Bonair farm all the way around and to come in on the home site along the flight path originally charted. They circled and landed on a lawn that separated a two-story white plantation-style wood manor from a shop, farm equipment strewn in its outside yard, the shop doors open. An immaculate late-model Range Rover and mud-spattered nineties-vintage extended-cab Toyota Hilux were parked side by side in the drive. Servants emerged from the front door and shielded their eyes from the sun to watch the bird set down.

***

Helmsworth Bonair appraised his guest generously, taking both hands between his own. Morland had drunk lemonade, settled into his quarters, had his shower, and he now marveled at how the rattling air conditioner managed to cool the well-anointed library so well. Master Bonair bade him toward an overstuffed armchair and remained standing within reach of the roll-away bar.

“With the day half gone,” the planter announced, “the only civilized thing remaining to us, I venture, is to drink.” He chuckled and iced the shaker with tarnished silver tongs and dented the bottle of Tanqueray. He unscrewed the vermouth cap and held it over the shaker for a full three seconds before screwing it back on. “I hope you don’t like yours dirty,” he smiled, “lest I shall have to call up a guest tumbler.”

“I’m always easy to please on the first round.”

“I have olives if you like; I prefer pearl onions.”

Morland waved his pearl onion consent with a ready smile.

A servant knocked and entered with a plate of canapés, and Bonair thanked and praised the girl in Kriol. She flashed her brilliant white teeth in a wide smile, glanced at each man in turn, and withdrew with a curtsey.

“Conch fritters; quite tasty, I’m told,” Bonair gestured to the plate and stood to withdraw cigars from a humidor at hand to busy himself with a cutter. “Food tends to intrude indecently upon my afternoon tipple,” he excused himself, “but by all means, help yourself.” Morland bolted two, dipped in an orange hot sauce of inscrutable origins, before relenting to accept the proffered Partagas. He leaned back away from the food and savored the taste of cold gin in his exhale to allow his host to speak freely.

“Mister Morland, I am having second thoughts about all this business,” he began, his pale blue eyes steady beneath unkempt white eyelashes. “I am sure you have been made aware that my neighbor and I have little with which to see eye to eye, but that has nothing to do with my cooling feet on this whole affair.”

“Mister Bonair, I am an engineering consultant and have no stake one way or the other in whether you sell this land or don’t. I’m here in a strictly technical capacity.”

“You see, Mr. Morland,” Bonair ignored the intrusion, “I am of Bayman descent, and despite what the roots class and aggressive chinaman and hungry creole and increasingly the brazen foreign tourism investment class would lead the credulous to believe, I, Helmsworth Bonair, I am Belize. The taints in my bloodline do not speak so much to historical indiscretions as to the the ineluctable virility of my forebears that carved this wilderness into a sort of society, rough though it may appear to the uninitiated.”

“You have a nice spread, here, Mister Bonair.”

“Please. What friends I have call me Helms.”

“I can count mine on a single hand and have fingers left over, including the middle one,” Morland replied. “I assume it’s the same for everyone. I sometimes answer to Hank.”

“Well, Mister Hank, this land is my blood, and my blood is this land. “But it is a changing world, my new friend.” He stood to pour more gin and repeat the vermouth charade. “And my children and grandchildren are more interested in their I-Pads and Facebook profiles than in coaxing a living from the land, and of course this is troubling to me in my advancing years.” He handed the drink to his guest. “I haven’t an heir actually worthy of the estate, Mister Hank. I don’t say this to diminish the qualities of my progeny, God knows I love them, but we have passed a knick in time, of sorts, and none of my sons, nor the husbands of my daughters has the grit required to see it through. It’s no criticism nor lack of character just an unforgiving consequence of a world in flux. Still, I can retain this and have Campo—he’s my farm manager and will be your guide tomorrow—run this place and post the profits, and I can bind the holdings into a trust that can keep my heirs in pocket change, perhaps for another couple of generations even . . . perhaps. On the other hand, Mister Hank, there is something appealing about a clean break from the material obligations to the fruits of one’s loins. From the other world—the one beyond the great mystery coming up on me—it is likely to prove difficult to intervene in one’s favor.”

“Do you mind?” Morland gestured to the vermouth, pouring a gentle dollop in his glass and retrieving a couple of ice cubes with the tarnished tongs to drop in.

“You have some temerity, young man,” the Planter harrumphed, “to engage in such blasphemy here in my very own study and in my presence to boot.” He laughed. “Perhaps I am but a remaining mahogany in an outback where the saws have never reached, yearning day in and day out for the daily sun and nightly rain, eking it out in the time remaining. You see, Mister Hank, I know the saws are coming for me.”

“Now that’s a martini, Sir!”

“Bollocks, lad!” Bonair smiled magnanimously. “But to each his poison as his own due. Gives me headaches, personally.”

“Yes,” Morland agreed. “Me too. Speaking of old mahoganies, can I ask you a question, Mr. Bonair?”

The old Bayman allowed his glance to settle into a stare. He liked this man but smelled about him the musty air of the reaper. He was unbowed by his fate to a sedate retirement to St. Georges, the bouncing of great grandchildren on his knee by day, contract bridge and gin by night, fortnightly visits to a vetted courtesan as the wife tended to the staff and fussed over the grounds and tea times, decay and opulence. “I like your style, Mr. Hank,” he pulled on his Cuban. “Ask me anything you please.”

“Why did your people not log out the mahogany on your property?”

“I don’t follow, Mr. Hank. Our fortune was hewn from mahogany.”

“But you didn’t log out the full extent of the property. Why not?”

A silence stood between them, and the old man’s face drew taut, and he pulled again on his cigar and took a drink, which after a long silence loosened his edges a bit.

“You mean the highland sector? By the Monkey? I noticed you overflew it on your way in.”

“Yes sir. The highland sector. By the Monkey.”

He had another drink and another smoke. “Never got around to it, I suppose,” he replied at last, “something to leave for those that follow. Have another fritter, Mister Morland, before the grease congeals.”

***

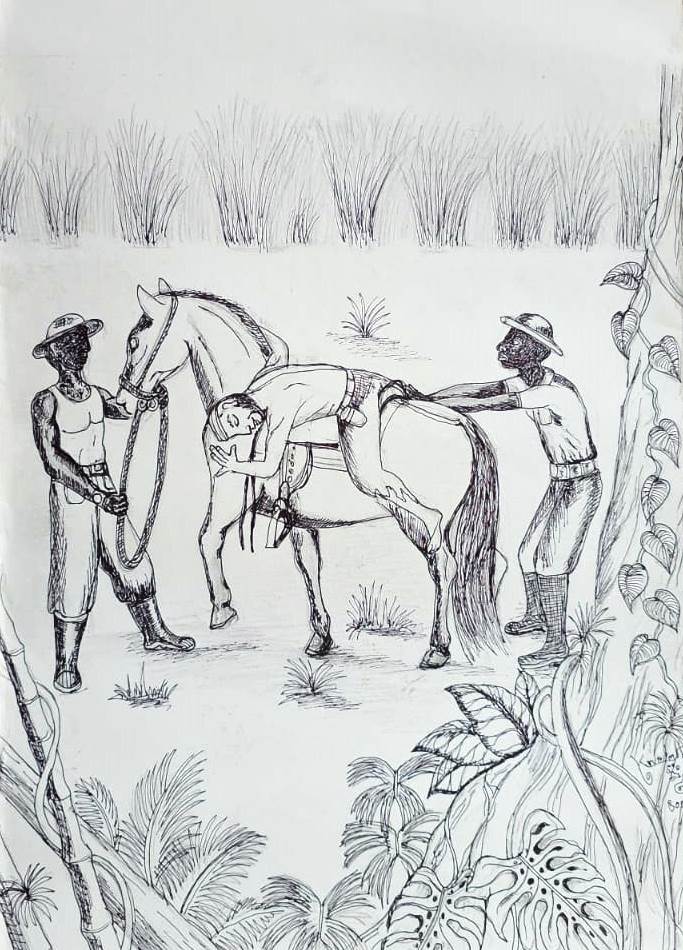

Morland deconstructed the itinerary and smiled at Tonio Campo, the affable farm manager empressed into service as today’s minder. Two farm hands held the four horses as the two principles sorted things out.

“The plantation is of secondary interest to my clients,” he cajoled. “We’re really most interested in the river frontage, particularly to the west, up in the Highland Sector.”

“Well,” Campos picked his words carefully and worried his chin between his fingers. “The boundary region of the Old Place—the highland sector—is too rugged for horses. But we can skirt below the forest so you can have a good look at its boundary and come around to the river and then follow it down and circle back around the fields in the afternoon.”

“I don’t mind hiking. Why don’t we do like you say, only have one of your men take the horses around the base of the hill. We can hike up and across the ridgeline plateau where that old growth is and cut down to the river near the boundary and hike down to meet up with the horses downstream.”

“Oh Señor Morland, is a very long and difficult hike. And dangerous.”

Morland pulled his map out. “It’s less than a mile across the ridge,” he pointed out, “and no more than two miles back downriver. It shouldn’t be too difficult.”

“Well,” the burly man cocked his head doubtfully. “It is more difficult than you think. Besides, if we do all that we cannot possibly get you to the meeting place with the Carranzas on time.”

“Why not? It’s only four miles further and we’re mounted and have till five this afternoon, all day long. There’s plenty of time. The distances are minor, really.”

“Oh, but you do not understand the forest, Mr. Morland, not this forest.”

So, they skirted the highlands on the horses and rode a trail that straddled the edge of the old secondary with meadows that gave to cultivated fields. They hugged the break in slope at the edge of the rise, and Morland looked up to his right as Campo kept pointing out features to their left. They dismounted for lunch on the bank of the Monkey River. Morland estimated at least 10 cfs of flow, but the drop he needed to see was all upriver. He marked a GPS way-station point and keyed in a log on his phone and snapped pictures. Downstream the land gentled, the river meandering lazily toward the coastal flats.

“Why do you not want to go up there?” Morland pointed his thumb behind them at the highlands as they retook their mount to follow a trail downstream in and out of trees on a flat gentle plain.

“The Old Place? Nobody goes there anymore. It has . . . memories.”

“What do you mean, has memories?”

Campo cast about, looking for the right answer. A serious man unused to dissembling, he picked his words carefully.

“I don’t know if it is true everywhere, but I suspect it must be, that there are places where things occurred that left an imprint that forever alters the landscape. The Old Place is such a place.”

“You mean . . . it’s haunted?”

“Oh certainly not,” the foreman harrumphed. “Still . . .”

When he found no further words, Morland prompted him. “Still . . . what?”

“Well, it has so far resisted being logged,” Campo offered by way of explanation.

“You mean people have resisted its being logged?” Morland asked.

Campo looked at him sternly. “No man has resisted its logging. It is the forest itself that resists. Perhaps it is haunted,” he turned to smile vacantly, releasing the pullets upon scattered grain. “That would be perhaps the easiest explanation. You could say that it has faced its loggers many times and has always managed to prevail, and there it stands.” He shuddered and when Morland turned away, he crossed himself.

***

“So it’s a Hatfield and McCoy thing,” Morland concluded for the three brothers that received him in the Carranza hacienda after his handover between the mutually suspicious Bonair and Carranza contingents at the Aguas Prietas Bar on the highway.

“More like Romeo and Juliet,” the youngest brother, Mario, a dapper man with a fast smile and intelligent eyes, replied.

“To hell with your Romeo and Juliet,” the middle brother, heavy-set, unshaven, and dour, glared at his brother. “Don’t be morbid! Little Mario,” he turned to their guest, “is a hopeless romantic, a poet if you can imagine that.”

“Julio’s our family stoic,” Mario clarified.

“Enough of this nonsense!” Sancho slapped his hand on the table. The oldest brother, a man in his mid forties, clearly called the shots.

“Look, fellas,” Morland sighed. “I don’t care whether your mother is Helmsworth’s sister or the Queen of Sheba; it’s not my business. You help me do my work, and I will help you sell your ranch, if that’s what you want to do.”

“We don’t really want to sell,” announced Mario.

“Yes we do,” countered Julio.

“But we want four and a half million,” clarified Sancho. “Three is just simply not going to do.”

“I’ll see what I can do,” Morland dissembled. “But you have to get me to the Old Place.”

The brothers looked at one another, then down at the table. Sancho tapped his fingers on its surface. Julio struck the head of a match with his thumbnail and lit a cigarette. Mario leaned forward to cradle his chin with his thumbs and grin. “Now we’re talking,” he smirked.

“What do you know about the Old Place?” challenged Julio.

“The Old Place is Bonair land,” Sancho declaimed. “They will take you there.”

“No they won’t,” smiled Mario. His brothers turned to glare at him. “Our Mr. Morland is not going to be so easily deceived. He knows better than that!”

“If I can’t hike the Old Place,” Morland said, “I can’t recommend this sale.”

“Taikbun might be willing to take him,” Julio ventured.

“Perhaps after clearing it with the oracles,” Mario replied. “Spilling the blood of a chicken or two over his bones . . .”

“Mario, enough of this insolence,” Sancho said. “Mister Morland, I will take you all over our property, show you everything you need to see. We will throw our books open to you.”

“Both sets even,” Julio ventured hopefully, earning a wry scowl from Sancho.

“But trespass on Bonair land I am unable to do. Why are you so interested in the Old Place?”

“My clients aren’t interested in running cattle,” Morland replied. “And they’re not too keen on farming rice. Personally I think your spread is a great place. But my clients want to build a resort—as you know—and the right place for that is at the Old Place.”

After the silence the intelligence merited, the brothers broke first into smiles. Looking at one another they began to chuckle. The mirth grew to open laughter.

“Look,” Morland glanced around at them. “Keep your Taikbun and his oracles; I don’t need that.” He pulled the property map from his pack and put it on the table before them. “Take me here tomorrow,” he told them, his finger marking the northwestern boundary of their property in the spring feed zone. “Leave me there, and I will cross the river and go on my own to the Old Place and make my own way back to Bonair’s. We will travel along the southern property line and up this ridge,” he pointed on the map, “to get there. The day after tomorrow, you will pick me up again at the Aguas Prietas like today, only at nine in the morning. Send your smoke signals—or however you pass messages to the Bonairs—to let them know. I will leave my main pack with you and travel with field tools only. Have horses and a guide and whoever else ready the day after tomorrow, here,” he pointed to the southeastern boundary where the alternate road across the hummocky ground was possible, and we will follow the land upstream till here,” he jabbed the map very near the Monkey River in the flats that bounded their main pasturelands and will cross the pastures back to the house, here, and I’ll call in the chopper and my work will be done. Is that agreeable to you?”

The brothers looked at one another and at their guest and mulled it over, reaching an unspoken agreement. “Get out the bitters, boys,” Sancho announced, reaching his meaty mitt across the table to pump Morland’s hand in a perfect goldilocks handshake. “We got ourselves a deal!”

“Where are those dancing girls?” Mario wanted to know. His handshake was cold and firm, his palms soft and dandy.

“How’s about supper,” Julio growled. His handshake was like a temblor, his palms violently callused, and Morland withheld the wince it evoked. “I’m starving!”

***

By midday he had sweated out last night’s booze and cleared his head. The early going was gentle and easy along the southern margins and pasturelands, in and out of stands of trees, Julio showing him the lay from a magnificent steed with which he fused in the saddle. But as they wound up into the mountains they dismounted and walked the horses. The day was cloudless, the sun very hot, and Morland sweated profusely. He saw no reason to dismount over a little mud and a few narrow trails over steep drop-offs, but Julio was ten times the horseman he was, and he followed the gruff heir’s lead and rode and walked as his guide and accompanying cowboys did. He took extensive bearings and made copious notes on the IPhone and took many pictures. Julio sneered at the city-slicker engineering in progress, but the ranch hands that rode along were interested in the camera, and Hank handed it around to assuage this curiosity.

“Now, you take a picture of me,” Hank told the youngest one, whose eyes lit up. He pulled alongside him and showed him the workings of the camera, the on/off button, the zoom button, the button to take a picture, then stood off and posed. “Now do it vertically,” he pantomimed. “It will make for a good shot. Good. Now try the zoom.”

They came together and Hank showed the men leaning out from saddles the images the boy had just captured. Julio stood his horse further up the trail to ignore them. After downloading the images, he would leave the camera with the boy tomorrow as a gift. But it slipped from his grasp and fell to the ground, where it struck a rock. The boy was off his horse in an instant and retrieved the instrument crest-fallen to hand it back up to their guest. It was broken, one down, leaving only the camera on his phone for the rest of the survey.

Last night’s curried kid and fried yucca had soaked up the evil liquor well; the brothers would not reveal the herbs and roots steeped in the moonshine rum. It was the Carranza blend of bitters. Family secret. He suspected gentian, chamomile, goldenseal, bitterroot and toad-squeezings, but it was as indeconstructable as the Bonair hot sauce, something you had to either refuse outright or throw caution to the wind about. The night had brought alternations of erotica and horror to his dreams, and as short as it was, seemed to stretch around the world, fast on the heels of Apollo’s horses, so that when he bounded awake at six he felt that he had aged a year but sat up from his pallet chomping at the bit, a sixteen-year old eagerness saddled with a thick head and sixty year old knees. He had drunk water lustily and in the grey light remembered suddenly that he was retiring from this work but neither why nor how he had come to this.

Many drinks of water later, he sat on the hillside and shook his nearly empty water bottle and listened to the clops of horses fading until they were overcome by the burble of the river coming from the opposite direction. He sat on an outcrop, his back against the cool limestone, and drank his last swallow and waited and listened a long time to let the forest get past the disturbance of horses and men. First he heard birds resume their song. A squirrel then emerged from the side of a tree to stare at him and came around the tree to twitch its tail and finally after many minutes to inch toward the base and onto the ground to forage. A toucan called in the distance. Far away a troop of howlers weighed in. The murmur of the river rose and fell in its familiarity, but it was some trick of his head; the river was the singular constant, and it flowed in the gorge that sank from his terrace fifty meters or so to the north. The ground was dappled from the sun’s penetration of the uneven canopy of this young forest. A passing cloud cut the brightly contrasting hues to dull greys and intruded on the birdsong and caused the squirrel to shake its tail more fervidly and glance around to reassure itself of the nearness of trees. Morland discovered a small boa coiled in its hidey hole in the rocks near where he sat, patient for its eventual ambush of a small passing creature.

Derek would be thinking about his bunk about now on his North Sea platform. He would be pulling the logs and maps and cuttings from the shaker table into his focus to settle his mind before sleep. He would imagine himself rolling in the surface chop despite knowing that the platform was engineered to not actually move. Perhaps he was fearless and hungered for the barrenness of the platform at night in twenty foot seas and the combustion of warm European and cold Scandinavian air over his head. Gotta cut your teeth somewhere. Better, he figured, someplace hard and mean.

He took a way-station point and logged it on his phone and snapped pictures. He had three bars and ignored Marcello’s texts and voicemail. He looked at the digitized plot maps on his phone and confirmed his position, taking note that he had only half a battery remaining. He was thirsty and tired, his knee tender from the ride and its many dismountings and remountings. He stretched for a long time after standing and loosened his muscles and ligaments. Dehydration from the bitters had his muscles tensed, and he hungered for citrus. Perhaps above the falls he listened to was a former homestead where there would be a decayed orchard. Certainly there would be springs.

He reached down and pulled the boa out of its hole and gently slapped down its slow and awkward efforts to bite him. he gentled it down and let it wrap around his arm and kissed the top of its head before gently unwinding it to return to its little nook and walked through the glade and did not have to use his machete as he worked his way upriver, angling toward the water. He hit a trail on the edge of the gorge and followed it as a light rain began to fall and howler monkeys piped in from across the river. A crossing agouti paused in the path to look down at him and twitched its nose and vanished. The river, louder now, began to quiet down.

He cut into the canyon and ate star fruit from a loaded tree abandoned years ago and made the river at the uppermost confluence of Monkey River tributaries, Momma and Poppa coming together, where he startled a tapir cow and her speckled calf. She threw her head up to take in his smell and bustled off into the vegetation with junior, and Morland waded to the middle of the confluence, thirsty, and splashed himself and wetted his hat before setting off to scout a spring up the left fork. There he drank his fill and sat a long time before filling his bottle to head back downstream, the light now yellow in afternoon’s advance. The breeze blew gusts of cool air from the ridgeline down the channel to push aside the still heat and enliven the lengthening afternoon. On the Bonair side of the river he found an old terrace remnant and a compliant boulder and took a seat to look over the terrain and his maps.

Down, oddly, to one bar, he was less than two miles from the Bonair Mansion and less than a half mile from their closest approach yesterday on horse. He checked the elevation and pulled up his notes from yesterday and found himself working with 200 feet of head. The flow was smaller here, but still well over five cfs. That was 50 kilowatts, plenty to work with, and this confluence was an ideal intake point. He took many pictures of the canyon controls and walked up both tribs to have a better look and walked the river till he found a good constriction, which he measured and used the matchstick method to estimate surface velocity. The continuity equation yielded a 7 cfs flow estimate, and the method underestimated by at least 35%, so the potential was well over 50 kw, edging closer to 75 kw, and it could be made to work.

He looked up the slope to see how to best climb it to get up to the Old Place. He stepped around a fer de lance coiled on the bank. He had been bitten three times by poisonous snakes, as a teen by a rattlesnake in northern Mexico, eight years ago by an eyelash viper on a Nicaraguan job, and lastly, by a krait in Laos five years ago on a job that went very south fast. But never by a terciopelo. Knock on wood.

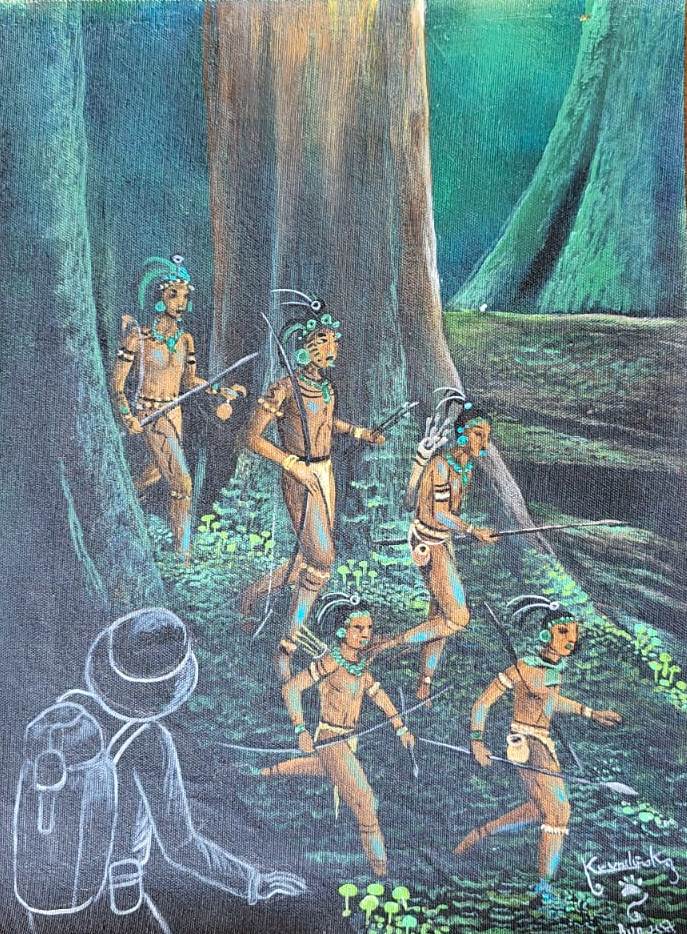

The wind reversed itself, and now a lowland rush of warm air from downriver announced a change in the dynamic of the day and pushed all the highland thunderheads back and it quit raining, and he hiked his way out of the canyon under a blue sky, its streaming light filtering through the leaves of the secondary trees that grew on the slope. But on the plateau the ground grew level and the primary grove was massive and ancient, its interior dark but clear of brush, peopled only by massive tree trunks and the spongy ground from which they sprang. He weaved his way through the old copse wending around the trees in a meandering progress, following an interwoven grid of pathways that he could not see but sensed connected by a coursing network of energy that seemed to steer for him a path of least resistance. His footing was solid everywhere, and the walking was very easy. He sheathed the machete, drank water, took a waystation point, saw that he had no cell coverage, and walked on. As the light shrank the canopy grew more lively with the sounds of animals, and when the howls of monkeys began the insects and frogs stepped up their acts to compete. From the deepest darkest part of the old growth in what he imagined to be its middle, a lightening grew ahead, portending the forest’s edges along the plateau boundaries, and he thought that to his right, he might have an overlook of the rapids of the Monkey, whose waters he could hear as a distant murmur. Something caught the corner of his eye and he whirled toward the deep interior where men ran among the trees, huddling low, copper-skinned and clothed in loin cloths and skins on their shoulders, weapons in their hands. They were spread out and darting low, and he watched them weave noiselessly in and around the trunks along the nodes of the energy network that now shone with traces of chemical light, the nearest apparitions only a few feet from where he gaped after them in their fleet, noiseless passage. They were painted and wore grim scowls and had lean muscled frames that bounded effortlessly through the forest as if gliding across the surface. But they were running, on their way to a grave encounter, and they paid him no heed and kept their eyes ahead of them. He blinked his eyes and slapped his cheek. But they were gone, and with them they took all the sounds of the animals and the overhead breeze and drew a cloud over the afternoon sun to leave the air inside the forest deathly quiet, the light very grey, everything shadowed and still. In the darkest part of the copse, the vapor they had dispersed in their fleet passage rose from the ground and collected to again hover above the floor at waist level as a gentle mist. He took off his hat and wiped the sweat from his brow and waited for his racing heart to settle. He mulled the hallucination and suppressed the fear rising in him. There was a rational explanation, he knew; there had to be, somehow. Probably the toad squeezings in the bitters.

He turned toward the forest’s edge with a new inspiration but stumbled over a rock hidden under the spongy humus and tumbled freely to the soft ground rather than twist his knee worse and lay prone and clenched his teeth against the pain to size himself up. He pulled to his feet and limped forward and tried to stretch his leg, but it would not fully extend, and he put his hands around his braced knee to gage its swelling beneath the fabric and its aluminum supports and stretched to test its strength. He pulled himself up to the base of one of the mahoganies and sank down to sit in the softness of the forest floor. He leaned against its bark, and the air around him throbbed with the shrieks of a thousand chainsaws, and he looked up at charred stumps and choked on the smoke that wafted around, the open sky above him brown and mean from the haze that turned the sun’s glare into an impotent gesture barely strong enough to allow a reckoning of the acrid miasma surrounding him. His back burned from the smoking stump he reclined against. He leapt away from the fire to find himself alone back in the same cool forest as before. He stood for many minutes and thought about this but could not assimilate it and edged gently back to the tree and held his hand out to it for many seconds before overcoming his fear to finally touch it. But nothing happened, and the silence and stillness lingered. He felt eyes upon his back and whirled to study the edges of the trees behind which something might be hiding in the mists, and he felt the eyes upon his back again, this time closer, and he turned again upon the haunted stillness and felt the hair of his neck rise. He shuddered as a growing coldness sent chills down his spine and left him shivering in the still afternoon heat of the misty wood.

Unnerved, Morland drank water and picked up his pace to stretch the knee. He could ignore the pain, but the weakness he could not, and he favored his left heavily and began to tire from the brisk pace. He reached the edge of the forest and listened to the river down the slope to his right. He hiked the plateau’s edge, settled a bit to be out of the middle of the trees, and emerged onto its tongue. Here he calmed his nerves more and looked nervously into the dark thickness where he had suffered his little freak out. He laughed at it and lowered himself along a small ledge and settled on a rock and leaned back against the wall to look out over the lowlands. Old secondary stretched down the slope and out across the land, and to his left a mile or so the forest gave way to rice fields. The Bonair homestead was another half mile or so beyond, and he could make out dust lifted by a truck moving on the entrance road. The Carranza pastureland peeked from above the tops of the trees that lined the river to his right, but that side of the river was rolling, not flat like the Bonair spread, and he knew their homestead to be hidden in a hollow a couple of miles to the southeast beyond his line of sight. He dozed in the falling afternoon and awakened in his dream to find the sun high in the sky and the rice fields and pastures replaced with the trees that he knew in his dream to be behind him, not before him, multiplied now into a massive forest that stretched unbroken across the plain all the way where the rice fields should be as far as he could see and beyond, clear to the sea. And right below him, at the base of the slope upon which he dreamed, an opening was carved out and a village stood, a pyramid its rising locus, its townsfolk walking to and fro across the cleared flat amid thatched dwellings surrounding commons criss-crossed by brown foot-worn paths, the trees at the edge of the clearing shading the bucolic scene, from which distant laughter and conversation intruded upon his reverie like the chirps of unseen birds or the roar of the ocean inside a shell. As the dreamed sun grew more oppressive, he lifted his canteen and drank deeply and found himself the conductor of an orchestra, the forest his symphony, wanting but for a baton. But then it was in his hands, an aluminum wand that he waved at the forest below between drinks from his bottle. But he was unable to tame his thirst, and the orchestra got away from him, the string section rising up against the horns, the drums pitching into an ever more frenetic rhythm, all of it discordant but for a single keening that rose from the land. The piercing sun warmed his eyelids and he opened his eyes as dusk fell around him. He found himself clutching a hinged metal piece of his knee brace, its tatters on the ground before him and threw it to the ground in disgust. He uncapped his water bottle but found it impossibly empty and looked with thirst upon the wet spot where he had apparently poured it in his sleep. His hat was gone. He looked up to gage with new respect the resources of an adversary he had not meant to awaken and wondered where the conventional sounds of dusk could possibly have fled. Where were the insects, the birds, the frogs? Where was the breeze that should rise out of dusk’s blend of lowland warmth and highland coolness? The rice fields had turned blue in the falling light and the shadow line from the forest behind him had now captured him into its mantle of shade and edged steadily down the slope before him, the shadow a living thing covering ground fast with Hank Morland caught up in its advancing grasp.

He withdrew his GPS and took a way-station point and entered the data into his phone—which still had no signal—and wanted very much to get far away from this place. But something held him rooted to his perch, tendrils creeping gently from the earth to coil around his ankles and and twist upward to envelope him and gentle him back down to the earth from which they sprang. He broke the trance in a sudden panic and stood panting and jumpy and looked all around him. Don’t lose your cool, Hank old Pal, he lectured himself, finding comfort in the familiarity of the Bonair place out there nearly within arm’s reach below the horizon, its windows now lighted against the quickening dusk. It’s right over there. You’re fine! He looked down to the GPS to confirm the bearing, but the screen was blank, the signal suddenly lost—something impossible that now did not even surprise him—and he shook his head and put the instrument away, pushing away the side of him insisting on a rational explanation to welcome in the desperation of a sudden sense of his own mortality that there was none.

The brambles on the slope were dense and he put his headlamp on in the falling light and skirted the ridge tongue for a game trail or something to make his way along, but there was nothing but the dense shrub that grew up the sides. He tried hacking his way through and got into the thorny tangle ten feet or so to pause, soaked in sweat, to see with his own math that he could not hack his way through this mess, that he would exhaust himself trying. He turned back to find the thickets healed and closed in behind his passage, and he had to cut his way out of where he had cut his way in only moments before. It was harder getting out than cutting in, the scars from his slashes now like ironwood. He stilled the upwelling of hysteria inside him and told himself that he had just taken his eye off his own path in and was now conflating it in panic with some impossible quality, knowing all the while it was not true, that he was consciously deluding himself, knowing that this forest healed itself. And still, as the light fell further, no sound rose but for the distant murmur of the river. There he would be able to find another spring to kill his thirst. And if not, he would drink its water and take his chances with any pathogens; he needed water urgently.

He chose a dry drainage channel as the least difficult way down the slope and found the going easier, the resilient brush more momentarily pliable to draw him in, and he kept moving forward and refused to turn around upon the insane spectacle of the self-healing brambles. There was rock in places in the ephemeral channel underfoot, in other places patches of moist sand, and he settled his nerves knowing that he would soon find a spring and rehydrate, and he made good progress down to a small shoulder of the slope where the drainage terminated in a small hollow that appeared to be a wet season pond, now dried, with mud cracks in its middle dimpled from the afternoon’s rain and brush encroaching on all sides. He mulled this over and scanned its edges with his headlamp to find an outlet and continuation of the drainage down the slope, but there was none, and he realized that it was a sinkhole and the end of his easy-going drainage route, and he now studied his mistake, too late to correct it. He should have returned from the ledge the way he came and made his way—however sheepishly—back to the Carranza’s, not tried to hack his way overland down and out of it. It had occurred to him, but the apparitions sprinting through the woods with their weapons and war paint had spooked him badly and better the devil he did not know, in this case, than the one he had just met. He regretted that now, but still wanted no part of the phantom war party. Anyway, with his knee now very weak and in his advancing dehydration, he could not possibly retrace his steps back uphill. He was committed. Maybe he should bed down and rest through the night and work it out under the morning light. A cloud of mosquitoes now rose from the silence to buzz around his head, and he found a small pebble to put in his mouth to put his salivary glands in motion to wet his mouth. He imagined dozing here despite the mosquitoes and thirst to drift into a slumber that might take him back to that dreamscape on the ledge, a real place to which he was intent upon not returning. His knee was sore and tired, but he could still go on, just that he must do it slowly and with care. There was no hurry, and he would slake his thirst soon enough. No rescue party was venturing into this forest to look for him, that much was for sure, so he had only himself to count on and had to keep his head and wits front and center, lest something very bad befall him.

He skirted the edges of the shoulder as he had the ridgeline above for the new best way down and gritted his teeth at the patch of saw grass that he could at least roll down and not have to hack his way through with the machete. He scooted down on his butt, moving mostly in the direction of the weed’s serrated nap and fell and rolled but did not cut himself too badly in the thickets. At the bottom of the patch he stood warily to pant heavily and take stock, his face and body on fire from the itch of the grass. He tore his shirt open to find himself crawling with tiny bugs, seed ticks or chiggers or ants or something that bit and stung, and he felt on fire in the panting silence, where the river’s burble could no longer be heard, and he tore his clothes off and dug soil from beneath the humus and scrubbed himself all over with dirt until the burning subsided and his breath began to still.

His sweat-soaked clothing now rubbed at the grit on his skin and chafed his groin, but the underbrush was thorny and he was better somewhat clothed and miserable than naked to thorns. He eased his way gently down the final part of the slope, cleaving an insistent way forward with his blade, each slash of the underbrush painful. On the flat, the vegetation thinned and the going was easier, and he wiped grimy tears from his face and limped cautiously toward where the river should be, craving its cool cleanness, needing to immerse himself in a pool and drink its water deeply. When its burble had still not reached his ears after a half hour of cautious walking, desperation grew in him and he limped more fervently and brushed away his caution but stopped himself to wind his way out of the new trance and take deep breaths and re-center. He checked the GPS, which had coverage again, and saw that the river should be right here, within a few tens of feet from him at the most—but was not—and he strained his ears into the silence but could not hear its faintest trace. He set out fiercely in the direction he knew it to be and hacked and tromped and buoyed himself against trunks and vines with his left hand as his right grew numb from swinging the blade, and he limped with great determination through the gashes he opened into the night’s brush. He felt the tempting warmth of panic rise in his throat and pushed it down by renewed vigor and heartened at the sudden faint burble that had to be the river and picked up his pace excitedly and stepped into a sunken spot and in his knee’s violent twist felt a lightning strike of blinding white surround him as he shrieked and fell forward, striking his head on a line of rock hidden by vines and brambles and thorns. He looked up from the ground to see a giant form rising in a slope of mounded jungle, the trees edged sideways to let it breathe, stars twinkling far above and fainted.

Hank Morland awakened to the giggles of children and found himself lain out on a pallet hewn from wood and vines in a clearing, the morning sun beating upon him, and as he came to and felt his knee throbbing, a copper-skinned woman, naked to the waist, grabbed the children’s hands and cast her head at him and scolded in their language and dragged them back away. He shielded his eyes from the sun and looked to the side and up at the limestone steps that rose to the summit of the pyramid from this afternoon’s dream and realized that he was dreaming again. By his reckoning of where he had made it down the slope into the night, it all seemed right, that he should be at about the dreamed pyramid place and looked up to find an Indian man, all regaled in feathers and furs and dangled fetishes and weapons standing at his feet and looking down upon him, his hands planted on his hips.

He felt his head, where he had struck the rock base of the pyramid and found it bandaged, a thick moist poutice pressed against the wound.

“To stanch the bleeding and steady the nerves,” the witch doctor told him in a language that was neither English nor Spanish but which unlike the woman’s utterances he understood with perfect clarity. “The only way out is up,” The man tossed his head up the glistening white steps of the structure. “From the top you may find your way out. Or maybe not; that’s up to you, you and Kukulcán.”

“Help me,”Morland replied. “I am thirsty. I am hurt and don’t think I can walk.”

“Have some water,” the man said, handing him a skin. “It may refresh your mind. But it won’t do much for your body.” The man offered his hand and pulled Morland to his feet, and he drank deeply from the skin. “I have helped you stand, but I cannot help you to walk or crawl. That’s up to you now that you have found our Old Place you so much wanted to see.”

“Who are you,” asked Morland, supporting himself first with a hand and then taking a seat on the first step of stones, hatless beneath the sun’s reckoning.

“I am not a who,” the man said. “I am a what.”

“You are one of the Old Ones?”

“I am whatever you imagine me to be.”

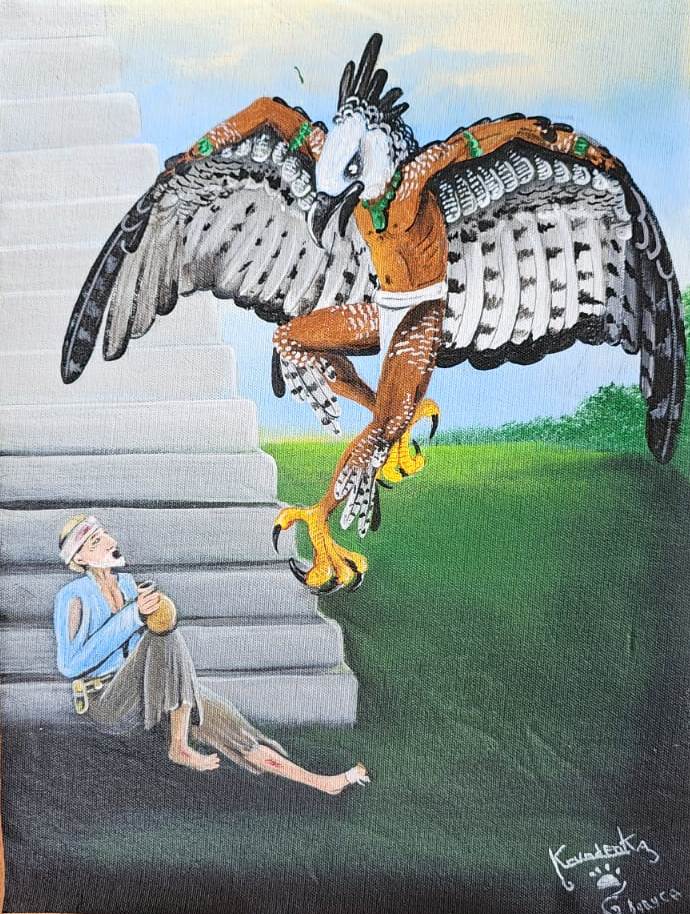

The man’s mouth sprouted a beak and he extended his arms that now hung with feathers, and his feet turned to thick orange talons, and the apparition became a harpy eagle and shook its head and ruffled its feathers in great delight and danced around on the ground, flapping its giant wings, waving its awesome head around in the awful light of the sun. The bird stopped and glared at Morland a last time and with heavy thumps of its long wings pulled itself into the air in a burst of sound and rose to monitor the man’s destined advance up the sun-baked steps of the white pyramid from even farther on high.

In his second wind the going was not so bad, even over the hot rocks beneath the sun’s pounding glare. He pushed his thirst away and found inside him the needed inner reserve and clambered up the white steps, oblivious to their heat and the sharp edges that cut into his palms and barked his ankles and elbows. He panted and wheezed on the acrid smoke that blew down from the Old Place plateau where the forest burned. He laughed defiantly at the sun and like Icarus before him rose toward it, dismissive of his purloined hat, contemptuous of his thirst, the way easier with each new step that he pulled himself up on, one after the other, ever forward and up. The villagers milled around fires below and took their meal and sat in the shade of their sentinel trees to converse and laugh and relax through the midday’s heat, oblivious to his travail.

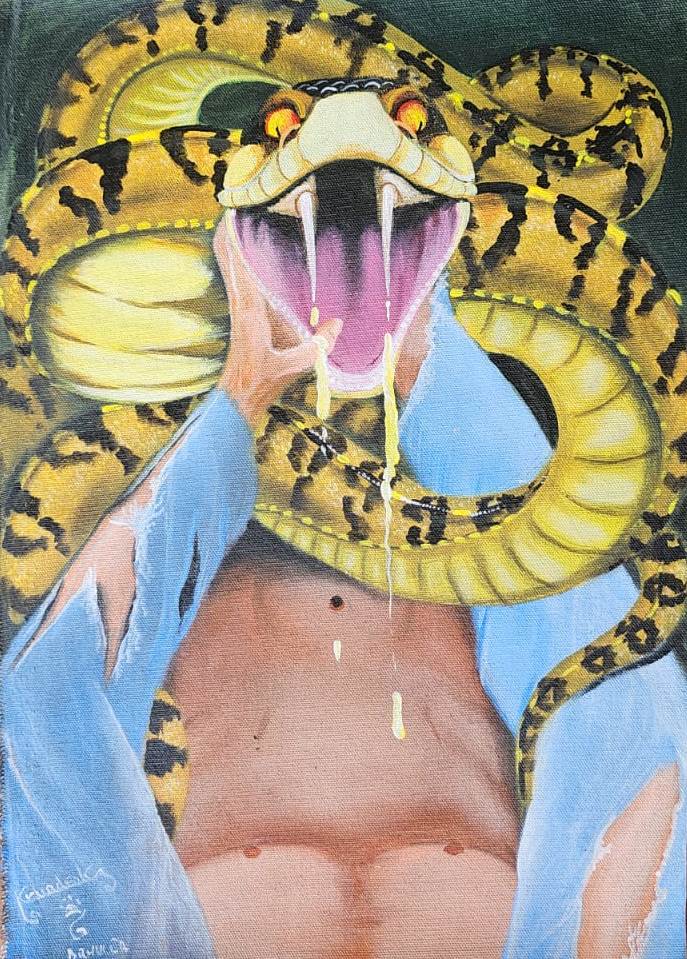

He came at last upon a stone landing near the very top, the white rock of its floor stained brown from ancestral blood spilled upon it year in and year out through centuries in spurts and pulses spent on the hot rock not too much unlike the pulses and flow of water in the river the usurpers—his own kith and kin—had come to eventually name the Monkey. From the vantage point of his new hopeful lookout he was able to see over the trees onto the familiar landscape of the Bonair rice fields which were very close by. An entrance to the pyramid was framed in very old and rough cut mahogany, and he reached for it to pull himself toward the shade that was there, confident that a vessel of water awaited him on a sacristy secreted inside the alcove. But the beam that he grasped was muscled and writhed in his grasp, and he awakened in the grey dawn to find a coiled viper’s head arched back with flaming yellow eyes, quivering to strike, and he released his hold on the snake’s body and looked up from the ground to see the animal glaring down upon him from above. He scooted back and away and threw his arm up at the last moment to defend his face and felt a great jolt and then a weight upon his arm and a thrashing that just as suddenly was gone. The viper examined him now with greater civility, its tail twitching more slowly, its work here clearly done. It coiled its body around the ground from which its head raised to examine him a final time, flicked its tongue to chemically absorb the summary state of affairs, and turned into the cool of the gentle light before dawn to casually slither back into the undergrowth and along its merry way.

He was very thirsty and turned his arm to examine the widely-spaced punctures as the arm began to throb, and he pulled his knife and cut himself deeply and squeezed the flesh to bleed himself. If it was a bushmaster, then he was now sure to pretty quickly die. If it was just a fer de lance perhaps he had a chance, perhaps. Because of his past brushes, he could more easily weather the bite of a lesser viper, he figured, perhaps. Regardless—for he had no idea what type of snake it was—he needed help pretty damned pronto. Around him the forest awakened in the twitters of birds and insects, and he was damp from the night’s dew. The GPS was working again, and he now had three bars on his cell. He was less than one half mile from the fields, within a few hundred feet of yesterday’s trail. He pulled Bonair up in his contacts and hit send, but the battery died at that instant, leaving him laughing through tears at the great use he had made of it in taking notes and pictures and leisurely looking at his maps to now impede him from now making the call that might save his life. Had he not dropped the camera yesterday, he might be fine now. But he had dropped the camera and was anything but fine as the world stretched and yawned all about him.

He nursed the wound to expel more blood and cut the hem from his shorts and fashioned a tourniquet which he tied off using his teeth for purchase just above his elbow. With another difficultly harvested strip of cloth he fashioned a sling and bound himself. He was unable to stand and rolled onto his knees and began to crawl through the thinning forest with his one arm. He smiled at the pistol he had been offered, how he might now fire it off in alarm to raise help. But he had declined the offer and crawled through the morning and began to hallucinate again, swimming through the soil of the forest toward a distant shore of water where he might finally drink and then stand again and walk.

He paid no heed to the voices above him, inured now to the forest’s deceit and was aware only that he was sprawled face forward on the trail he had reached before collapsing, a line of leaf-cutter ants crossing a few inches from his nose marching nobly beneath perennial loads.

“Snakebit,” came a voice. “Tommy Goff, sure.”

He felt himself being turned over but could not operate his eyelids.

“He daid?”

“Not yet, ain’t stiff. Still dying, sure.”

“I don’t raise a pulse.”

“What dat ting on his noggin?”

“Some medicine wrap, I tink. Been a doctoring hissef, sure.”

“We best get him back to the shop and call help.”

Let’s fetch him over da saddle. He a goner sure but ain’t nuttin lost in da tryin’.”

“Boss-mon warn im. Did boss-mon not warn da mon?”

“Some has to see to believe.”

Katie would be fine now in her final year, even if his will were successfully contested by one of the minor ex-wives. He saw Derek on a helicopter bound for London and some days of R and R and Sarah he imagined harmonically un-converged but putting forth a brave face against the boredom of complacency and plenty. His paralysis was not uncomfortable, and he had enough reptile DNA in him from previous encounters that he ventured he might live; the throbbing in his arm was faded now to a gentle deadness, his violent thirst now gone. He did not like the way he was laid over the saddle, his hands and feet dangling beneath the mare’s skittish gait, his snake smell surely unnerving to her, but his dislike existed only in his head, as a matter of principle. In his body it seemed natural, being flopped across a saddle face down, like an outlaw shot dead and being humped in for the bounty, and he turned his fevered dreams to cool purple mountains above a cold Southern Ocean and the prairies and rivers inland, the conifers of the highlands, and the animals that roamed there. His cottage was close at hand and he would grill the trout over the fire and wrap himself in warm clothing and turn out the lights to take in the cold mountain night from the porch and watch shooting stars punctuate the billions of galaxies all around and tipple a fine local vintage and feel whole and strong as the Milky Way turned above his head and the world beneath his feet and the tides of time moved forward and backward in constant ebb and flow.