La Segua

Aserrí de Desamparados February 5, 1948

She stood by the tarmac barefoot, dressed in a crimson bodice above a rider’s black leather skirt, her white-lace shawl incandescent against the deep brown of her bony shoulders. She had Isadora’s face, only with cat eyes, one yellow one blue. She recognized him as he passed slowly by where she stood on the shoulder. She wanted a ride or wanted him; she wanted something and wanted it without having to ask for it, and a drop of urine escaped into the silk folds of his boxers. It was Izzy, no doubt about it, only Izzy was dead; he had helped slide her dolled-up remains into a Los Santos crypt less than a week ago. He braked and slowed to make a wide turn back for her. Could it be that she was not dead after all? A long-lost twin sister? A spectral doppelganger? Or was it he that had gone crazy, settled on the face to apply to the body he would never again feel beneath the weight of his own, one whose geometry and mass extended merely in the stew of a memory to torture himself with alternating shame and schadenfreude?

After all, even if Isadora were not dead—which she was—how could she be out here in the black of night alone by the highway? Those catty little cunts in his wife’s circle blamed her cuckolded husband, of course, few knowing that she was banging our antihero on the side. So went the hypocritical spew: her husband was having an extramarital affair and with a common harlot, in fact, little wonder that poor Izzy had to run to her boudoir to escape the shame with a big old dose of scopolamine.

“Not before making off with an alimony fit for Hera,” our driver mused to the interior of the Packard. “Or are you somehow out here, after all, Izzy Baby?”

Hans Alexis Petrov lifted his foot from the accelerator and down-shifted to putter, not daring to look back. How could it have been Isadora, impossible, a coincidental look-alike, a false imposter. He idled on toward the turnoff of his own nearby driveway, a coward for not returning, a weakling for pretending ignorance. It was chilly and dark after passing the few street lights of Aserrí, but the air was still and quiet, a gentle mist settled in among the oaks. Hans drove a ‘47 Packard convertible and he drove it slowly, never in a hurry, rarely with the top down. There was a rational explanation; there had to be. The moon was a waning crescent but had not cleared the tree line on this cloudless summer night, and switching the headlights off, the milky way shone like a glowing platter’s infinite expanse into whatever was beyond what they all prayed to on Sundays.

Virginia Woolf had nothing on Isadora Arias. Caribbean pines that framed the cemetery of Santa María de Dota bowed beneath the offshore Atlantic wind, vigorous even this high up in the Santos Region. She killed herself with the tea of reina de la noche, and at 28 her suicide left an immaculate corpse, a wide-open canvas for an undertaker with necrophiliac proclivities, and when the death gurney slid past Dr. Petrov on one side of the crypt’s runway, his lover could not have appeared more life-like, her lips swollen with carmine tint, the folds of her silk dress moving in the stiff easterly wind. It was simple angel’s trumpet, Brugmansia suaveolens, and witch doctors used all of its constituent parts for different things all the time. Isadora had picked the pink flowers from the ornamental gracing her own front yard. It was no accident. Everybody knows reina de la noche and to stay away from it. You knew that, I knew that, Hans knew that, and so did Isadora. La reina belongs to the nightshade family, a cousin of the tomato and the green pepper, a New-World plant, pressed occasionally into Old-World services— it turns out. It is easy to make tea from the flowers, or eat them off the vine… You can also dry and smoke them. Some sleep with the flowers beneath their pillows to enliven their nightscape. But you don’t need the flowers. Every part of the plant contains psychotropic toxins, and lots of them. The belladonna alkaloids from the Angel’s Trumpet include atropine, hyoscyamine, and scopolamine, but it is the latter of these that is the most dangerous.

The sliding of the crypt board found its resting place inside the vault, somewhere short of the deceased’s head banging against the concrete end, and the mouth was sealed by a tradesman and assistant standing by with concrete block, mortar, a rushed veneer of stucco and finally a brass nameplate affixed once the sparsely attended ceremony in Santa María de Dota had broken, leaving only our presumptive cuckold Amancio, Hans, Emilia, and the decedent’s twin brother, Archer, to stay till the end.

The face plate read:

Isadora Arias Cardenal de Zúñiga

1920 – 1948

Why would she kill herself over the infidelity of her chinless, sunken-chested, male-pattern-bald, technocratic husband over a little extracurricular interlude with a sex worker? You had to be kidding me! After eighteen months of stolen moments with Hans, dozens of adulterous instances for anyone counting, how could Isadora hypocritically begrudge her husband, the constitutional attorney Amancio Zúñiga Cabrilla, a little poon on the side? Especially seeing it was paid for? Didn’t they have it made, Isadora and Hans? But she had really gone and fucked it all up. Let’s just hope she wasn’t fucking it up all over again. But it had to be Hans doing the fucking up of it, for after all, how could she fuck it up a second time around if she had died fucking it up the first time around to begin with?

Made bold by anger more than courage, Hans did a U-ey, finally, pealing out back to the scene, where an abandoned late-model Ford stood, its engine idling, its driver’s door open, low-beam headlights glaring through the roadside weeds to illuminate the trunks of darkened oak trees bounding the forest’s edge. A grunt, hooves, a whinny, and from the corner of his eye, the silver flash of moonlight reflected off a horse’s tail, the triumphant neigh, and it was more imagination than sight that revealed to Hans the image of a man bareback, newly reached by the ascendant sliver of moon, slumped forward and absent a saddle or bridle, clutching the neck of the magnificent beast with his arms, his thighs clasping the animal’s ribcage, then the fading sounds of horse clops at full gallop through the benighted forest untamed by trails other than Hwy 209 and its fractal ana1stomosis beyond Tabarca, Jorco and Acosta into the vast network of small Santos-region roads beyond.

San José Colegio Para Señoritas 12 octubre 1947

“I would eat him alive,” mewled Señorita Caridad Fischel a few seconds before the bell. She was the eldest daughter of the pharmaceutical magnate with outlets now as far away as Los Chiles and Paso Canoas. She merely suggested a head toss toward their French professor without actually leaning her high forehead in his direction.

“You should try to hide your poor tastes and reveal only those little fetishes that become you, dear,” her bestie smiled. Ana Cristina Durán was the granddaughter of Doctor Carlos Durán, our leading early-century warrior against tuberculosis. The Carlos Durán Sanatorium was still in operation, anchored to the slopes of Irazú Volcano against the offshore gales from both oceans that whipped across the cordilleran spine to stunt and bend our trees. The L-shaped building’s wooden walls to this very day harbored the cream of Central America’s high-stepping consumptive class; only in Austria’s Davos clinics might a superior institution for quelling the vagaries of the tubercular lung possibly be found, that no sure bet, and at several times the cost. Despite discharging cadavers at a ratio to inbound inmates comparable to sanatoria around the world, it was a revolving door in the Irazú gales, a lot of money at stake, tuberculosis still on the prowl and peripherally connected to our nation’s Gross National Product, just four years after the antibiotic cure was first isolated at Rutgers University by that German firm, Merck [and Company] ninety years after cholera had decimated this country’s population. Were Durán still alive, tuberculosis would be routed from Cartago, but Dr. Durán had been pushing daisies for 28 years now.

“Besides being an obvious weakling who has never allowed the sun to shine upon his chest,” Ms. Durán declared, “he is just a common teacher of secondary school. Nothing more.”

“You don’t see the animal prowling inside his garments,” Fischel said. “I do.”

“Give me a lawyer, a doctor, an engineer, even an accountant or business administrator. It will take a lot more than a horny professor to make me blush—even with his doctorate. You know, Don Hans does not have even the proper certification to teach us, Caridad, you know that, right?”

Voices stilled as Dr. Petrov tapped his stack of notes into order and stood beneath the bell. “Thank you, Ladies, and today, we shall start with the four-paragraph introduction of an eighteenth-century treatise of great renown, penned by a bourgeois prisoner doing time at the Bastille during the French Revolution. Señorita Durán,” he glanced past Fischel, smirking over his preternature, “will you please come to the front of the class?

“Philosophy of the Bedroom, Doctor Petrov?” Señorita Durán demurred.

“The year is 1795.”

“I doubt my father would approve.”

“Good thing we don’t require his approval, isn’t it, Ana Cristina?”

Her peers held their amusement to titters to avoid dissuading their jittery classmate from a spirited performance. To Petrov’s insouciance she smiled to spare him the withering scowl perhaps more warranted in this particular instance. “Very well,” she curtsied in submission.

“Are you young ladies all familiar with the cognate noun libertinage?” Dr. Petrov challenged them, spelling it out on the blackboard. Here is how it is pronounced in French ‘li•bér•ti•naj’ and in English it is much the same: ‘li•bér•teen-uj,’” he wrote it down. “And of course, in Spanish the word is libertinaje, with a “j,” which is the TENTH letter of both the English and French alphabets but the eleventh letter of the Spanish alphabet, given that pesky Castilian digraph “Ch,” which remains a letter, young ladies, along with “Ll,” and ‘enye,’ at least as of this lecture. Me,” he touched trembling fingers to his own chest modestly, I would ditch the first two, but enye really warrants its own letterhood.

He gestured toward to the wall on his left side. “If you have any doubts as to the precise French meaning—and libertinaje does arrive into our language from the French, Señoritas, of that you may be certain, then you may wish to recur to La Dictionnaire de l’Academie Francaise, perched in readiness on the south wall counter. He rapped his knuckles twice upon the surface of the desk that he leaned against.

Señorita Natalia Justina Carmona looked briefly sideways and up before standing to proceed in low-heeled pumps to the dictionary stand to make sure she wasn’t missing out on whatever Petrov wanted them all to take away from today’s lesson. Señorita Carmona may have had a whole lot of “-less” things going on inside. But shame was not one of them.

“The first three paragraphs will do; Señorita Durán. Then we can turn it over to Miss Fischel for the fourth paragraph’s dollop of honey.

“To Libertines,” Ana Cristine announced immaculately. She looked up toward the attention of all in the soft firm clasp of her once and future grip.

“Voluptuaries of all ages, of every sex, it is to you only that I offer this work; nourish yourselves upon its principles: they favor your passions and these passions, whereof coldly insipid moralists put you in fear, are naught but the means Nature employs to bring man to the ends she prescribes to him; hearken only to these delicious Promptings, for no voice save that of the passions can conduct you to happiness.

“Lewd women…”

The professor interrupted. “Notice de Sade’s use of the adjective obscénes, lewd, and not vulgaire, which we would translate as vulgar and obscene. “Do you recognize the difference, you young maidens, between the English words “lewd” and “obscene?” It is not so hard to be lewd without being obscene,” I think the Marquis was telling us. “But it is hard to be obscene without being lewd. Would you not agree, class? You think on that one and we’ll get back to it tomorrow.

“Now repeat again, Ana, with that voluptuarian tongue of yours.”

“A les femmes obscénes,” Ana Cristina repeated, a bit louder. “Let the voluptuous Saint-Ange be our model; after her example, be heedless of all that contradicts pleasure’s divine laws, by which all her life she was enchained.

“You young maidens, too long constrained by a fanciful Virtue’s absurd and dangerous bonds and by those of a disgusting religion, imitate the fiery Eugénie, be as quick as she to destroy, to spurn all those ridiculous precepts inculcated in you by imbecile parents.”

A slow clapping rose from the lithe hands of the dark-browed and ever serious Señorita Carmona, returned from her reference to libertinage in the Dictionnaire of the French Academy. Little Nati’s forthcoming inheritance gathers yet from gaming and prostitution rackets her mother and uncles have spread from the young-Turk central-valley philandering class and their impotent grandfathers toward rougher and down-scale but more populous Limón plantation markets. Why, the Carmonas were all over Crucitas, Abangares, and the Osa, delegations of hardened young hookers managed by middle-aged courtesans led the charge in the gentle separation from eager miners of the placers, veins, and disseminated ore of the gold in their pockets and what accrued as payment among the merchants selling them their fuel, liquor, food, steel, and general supplies beneath the daily toll of fevers, worms, parasites, tunnel collapses, vipers, crocodiles, dengue fever, long arms of the law, feuds of all sorts, a wide array of social diseases, and Carmona harpies arrayed against them. Soon there would be crews to work the railroads and then to attend to the needs of the unionized dockworkers of Limón and Caldera plus the skilled working class that would next break ground for the oil refinery planned for Moín. Already there was a growing sophistication to the perversions among San José’s elite, and there was a lot of money to be made in bondage, humiliation, water sports, homoerotic debaucheries and sundry other sexual idiosyncrasies not altogether uncommon among the republic’s political leadership and intelligentsia.

San José Colegio de Señoritas February 5, 1948

Class was on the third floor, and the day was cool, the windows open, ceiling fans laboring away. Dr. Petrov’s sartorial inclinations were the widespread vocabulary of a whole subset of school gossip. Today, he wore a pressed, cream, light-linen suit jack loosely over an extra-large low-thread-count white, cotton shirt, long sleeves closed with cufflinks sporting blue Greek opal set in 0silver, Italian tasseled loafers, and cream silk slacks with seams so rigidly straight that it posed a distraction to the young ladies in the first few rows that sat before him in the well-ventilated room to comprise the very apex of the Costa Rican society’s up-and-coming fair sex, many of them demeaning their station by imagining their turn at ironing the Professor’s slacks. Aqua socks, a celeste cravat, and a Panama hat completed his outfit. Teaching was reputed to be a mere pastime for him, and a proletarian one without a doubt; even the vulgar Carmona lass would agree; still, he clearly enjoyed his work and obviously had money.

It had to have come by way of his German and Russian forebears, so a bourgeois foundation could not be ruled out. Still, the exact mechanics of his wealth or lack thereof were not in rotation in the San José gossip circles, leaving his pupils in conniptions over what to make of this man beyond his regular presence in their masturbatory fantasies, a circumstance which led to the rise in demand for cucumbers at the downtown market, where kitchen staff of respective manors were left without recourse beyond boosting the vegetable buy, in a couple of cases having to actually double the quantities routinely procured (of cucumbers and zucchinis) given that so many went missing from pantries during this time, which happened during a strong El Nino Southern Oscillation event with all its attendant climate changes. These hot dry summer weeks were simply not the same without the salads and gazpachos to which the common cucumber was the indispensable ingredient.

Petrov’s proficiency in languages, the presumption of culture, and wholesale absence of shame left him a bit of a standout at Costa Rica’s Colegio Superior para Señoritas, the only “girl’s high school” in the country. Despite his penchant for fashion, he was known to be somehow impervious to the heat or born without sweat glands or something strange like that; even under the large incandescent lamps that lit the classrooms, his forehead might as well have been powdered with talcum. The electricity for the lamps came from the hydroelectric power developed and promoted by that Basque, don Jose Figueres Ferrer, native of San Ramon, recent hydroelectric Master’s degree from the famed Boston university with the initials Em, Eye, and Tee, recently back to stir up the political pot. Don Pepe, they were now calling him now, far and wide, to boost his street cred: quite possibly our nation’s next president.

The greater the perceived distance between don Pepe and his political coreligionists Benito Mussolini and Francisco Franco Bahamonde the better, given the former’s awkward manner of death and the latter’s retreat within a walled-off Spain to enjoy the fortune of his Republican revolutionary foes misreading the tea leaves by three years. And the unmentionable, of course, could simply not be mentioned, even if some elements of the Monchista hardliners had found common ground in several regards with that particular deceased European leader we don’t talk about (whose initials were AH). Figueres was an astute intellectual with deep pockets, and he quickly adapted to Calderon’s broadcast societal moves to co-opt the anarchy birthed from the Second World War. Don Pepe fell under the sweep of Dr. Petrov’s radar as AC power plants, spawned in Nikolai Tesla’s Ames mold from Telluride, Colorado, six decades earlier, spread like rice first through the nation’s affluent neighborhoods and downtown San José, and then into its industrial and agricultural strongholds to make more liquor, more coffee, more sugar, more dairy, grow more bananas, power more streetcars, and with air-freight within months of becoming a reliable commercial recourse, launch the up-and-coming carnation and orchid agricultural industry.

“I bet I know how to make him break a sweat,” claimed Alejandrina Acevedo Rodríguez, daughter of the president of the new dairy collective, Dos Pinos. Three weeks later, however, upon being challenged in his office while taking a make-up test that she had purposely skipped, Drina discovered while pulling a B on the exam that even the most reliable of her little tricks was insufficient to spawn even a bead of the salty from the largest organ of her professor’s body, even though she did pleasantly detect a trembling in the fingers on the back of her head that pulled her mouth even more fully around his smaller one.

The same could hardly be said for Durán as she read those three paragraphs. Her flushed face beaded at the hairline with tiny drops of moisture that her professor admired with a gentle smile before dismissing her to have Fischel deliver the fourth-paragraph whammy. Durán was fluent and Fischel struggled, or rather, butchered la belle langue, her tongue a dull cleaver. But the moisture extended beyond the hairlines of the young women in attendance hung in the air and lubricated the contact between surfaces both animate and inanimate as the rustle of fabrics bespoke of legs uncrossing to cross in the opposite direction and the smoothing of blue-satin lap rumples, blouses of flowered silk, and the rustle of stockings, nearly all made from nylon these days, a couple of the girls still sporting the old styles in cotton and silk, with wool way too warm for their tropical clime

The Deep Back Skinny 1774-present

Dr. Hans Alexis Petrov was born in St. Petersburg in 1903 and had two native languages. His father was Russian, and his mother was German and neither spoke the others’ language to him in his infancy, so he learned to speak both of them natively. But the Costa Rican maids from 1905 on spoke to him in Spanish so he had the trifecta down by the time he turned four. At thirteen he was trundled off to High School in Berlin, having mastered English in primary school. In Germany he was encouraged to read ancient Greek and Latin and went on once the many suicides from the Great Crash of 1929 were decently buried in the various capitals of the world, to make short work of Catalonian, Spanish, French, and Italian from undergraduate university studies in Andorra, concluded in 1931, where his family’s historic largesse had entitled him to study free of tuition, despite the Great Depression underway. An unsuccessful courtship with a Mexican bureaucrat’s daughter led him to Mexico City to make quick work of his Ph.D. and from friendships and travel between the end of the Great War and the years gathering toward the new one, he could now fairly boast of winging it in Portuguese, modern Greek and Arabic, though he no longer had anyone around him with which to practice these languages. He returned to Costa Rica in 1934 and quickly garnered a bit of a reputation in the capital as one of the few polyglots with Costa Rican citizenship. With his Ph.D. in comparative literature, he was a shoe-in for a well-paid turn as a full professor at the Colegio Superior de Señoritas in 1935—a much higher paying job than at either of the nation’s two universities—where neither the German nor Russian languages were particularly in vogue, and the School Board did not consider ancient Greek nor Latin to be appropriate subject matter for the child-rearing female half of the nation’s up-and-coming top crust. That left Dr. Petrov with English and French as the foreign languages he taught, beginning and advanced, though without a teaching certification or pedagogical background. He took Humanities and World History, as well, six preps, in teacher’s parlance, and one study hall period.

Hans Alexis Petrov’s German forebears immigrated to Russia in 1774 from Munich and grew their investments into important feudal holdings by the turn of the 19th century. They went full russification during Napoleon’s campaign, and while most of his ancestors spoke Russian as a first language, there were a few that spoke it with a German accent. Hans was dyed-in-the-wool in that way that simply cannot be bred out of certain Germans—perhaps even MOST Germans. Hans considered himself—and he knew there were others like him among Russian-German citizens—if anything, more German than Russian. Not by a lot, but by enough to count.

The passive aggression of first Tsar Nicholas II and then the restive Bolsheviks raised hackles with those predisposed toward self-preservation, and Hans’s maternal grandfather, tainted with a little Ashkenazi Jew from Hans’s great grandmother’s little infidelity, was quick to prepare for the Ivanov-Petrov-Schlesinger diaspora out of Russia and away from the sickles gathering town ward from the steppes. It was always a mystery as to why the old man chose Costa Rica, but in the final five years of the 19th century he managed to disentangle his finances from Mother Russia and left the lion’s share of his wealth invested with the Rothschilds. He chartered an iron-hulled tall ship, one of the windjammers then carting interoceanic goods between Europe, the Americas and the Far East to ferry all the kith and kin that would join him and all of their possessions as well as agricultural and even industrial equipment and shipped out of the then-permissive port of Gdansk in late December, 1904, and out the Baltic Sea into the Atlantic Ocean to land on the sunbeaten pier of Limón, Costa Rica, to moor next to a banana freighter on February 22nd, 1905, as the first Russian Revolution broke out with the slaying of unarmed protesters in St. Petersburg by the Tsar’s personal guard.

***

“Honey,” Hans announced, from inside the mahogany-framed ebony doors, hanging his hat on the rack just inside the bright ceramic-floored foyer. “I’m home.” Their house was hewn from the forest, the first-floor walls raised in mortared andesite stone, the second story in oak milled from where the giants were felled to break ground. There were no farms around. No cattle, no horses, no pigs, no goats, not even chickens for eggs, not till the other side of Aserrí, headed down toward Desamparados. Up here it was just the endless oak forest and the titters of the resplendent quetzal and ruminating grunts of highland tapirs mucking it up in the wetlands. Hans had not recognized the car with the door open and the headlights glaring into the understory, but it was a late-model American vehicle, clearly from the slice of society proximal to Dr. Petrov’s own station. Who would not have slammed on the brakes to make off with the lovely Isadora, assuming she was indeed the lovely Isadora and assuming her Casanova had no idea she was actually dead?

Husband and wife came together in a light embrace in the living room and Emilia Calderón Clays smiled at the tumescence beneath her palm’s southerly exploration and leaned forward across the sofa back to lift the hem of her dress and turn to release herself to him to moan as the slaps of skin on skin grew rhythmic and labored. The satisfaction was perfunctory with cyclic exhales, beads of sweat raised on Doña Emilia’s brow, and a trembling of the final two joints of each of Dr. Petrov’s eight nimble fingers and two countervailing thumbs.

So, Hans Alexis Petrov was close now to Rafael Calderón Guardia through this convenient marriage to the great man’s adopted daughter, Emilia, close enough perhaps to scuttle his father-in-law’s great socialist pretension, perhaps not. He had pulled it off, after all, and while he may not have loved his wife along definitional lines, he sure had a lot of practical lines of love tendrils all magnetized along her axial currents. It hurt not at all that she was good in bed, undemanding of his time, wealthy, and a pretty good cook. Not such a bad match if you wanted to know the truth. He slapped her on the bottom and buttoned his trousers around a flagged erection to make his way to the kitchen to lift the lids of pots on the stove to absorb its contents. It was Friday night, and with barely any work the Electoral Council itself imagined that it had settled on The Colegio Superior de Señoritas as its very own idea to serve as the polling station for the entire Central San José electoral province, the highest concentration of Calderón liberals anywhere. Dr. Petrov’s students were only too eager in their patriotic fervor to swear oaths and to ‘man’ the polling stands from dawn to dusk on Sunday, the day after tomorrow, so it was all set. Tribunal representatives would arrive the morning of the ninth to get the vote counting underway, breaking the seals with requisite pageantry and protocol. All things being equal, President Teodoro Picado Michalski, an adoring Calderonista acolyte of the previous four years, had stewarded enough political support toward the communist-loving Calderón to carry Don Pepe’s assigned day in the sun into a smoldering ash pit.

All things being equal, that is…

The liberal bastion of Alajuela could never carry Calderón’s torch without San José. And even though they posted guards to watch over the ballots in Cartago, Heredia, Alajuela, Escazú, and San José, nobody was anywhere close to imagining the surprise in store lying in wait for the nation at San José’s Colegio Superior Para Señoritas.

“Nothing to worry about,” Hans smiled at his politically expedient bride. “Your daddy is a shoe-in.”

It was Heredia and Cartago that would propel Calderón’s nemesis Otilio Ulate Blanco into the presidency should San José fail to make the difference at the polls to then begin to reverse the nation’s slide into outright communism. (Hear ye, hear ye!) Doctor Rafael Calderón Guardia had been bitten bad with the socialist bug and now had the Catholic Church behind him, set to continue with the transformation of our society in full progress to a collectivist pallet of sniveling takers on the dole, all of us urinating into the pigment of the paint coloring our society.

Social guarantees. Social security. Worker’s rights. Human rights. The assault upon the landed gentry and the monied class must always be doomed to fail. Without the means of production delivered by the gilded industrialist bearers of capital, the worker class will cease to exist and society will fall off the ledge into a bottomless pit in a race to see which class can eat the other first! Hans retrieved a 1938 Chilean Sauvignon Blanc from the chilled white-wine cabinet of the Petrov Manor wine cellar and delivered it decanted on ice to serve in flutes to accompany Doña Emilia’s Coq au Vin, steaming now from the oven. They sat beside each other at the corner of a hardwood table that extended to Emilia’s left-hand side as far as you could see. The table seated 9 on each side and 2 at the ends. The chicken and released vapors of buttered rosemary, and there were dipping bowls of Hollandaise for the steamed artichokes, and it was all tender and succulent. In the end, Emilia sent her over-schooled groom back down to the cellar for a bottle of port and slapped him on the behind along his way to fetch the accompaniment to the little custard thing she had coming up. She was good at caramel flan and didn’t much care for coconut flan, but this was her first hand at crème Brulé.

Of course, there would be armed guards to defend the ballots against electoral enemies of whatever stripe, Hans remembered. There would be a defense against malefactors or benefactors, their identities depending more on your own side in the open battle between the liberals and conservatives, until it didn’t matter anymore, until they all blended together to exchange roles to return as traitors. How the Conservative, Church-backing Imperial (A)pologist of Calderón could switch over to open socialism was a betrayal in itself. But that hardly gave the reactionary Figueres clan the right to outcompete these lightweight adversaries with even more leftwing positions. But the nation did not exist inside a vacuum and the fast-moving events that followed European hostilities kept everyone on their toes, everyone that is, except, apparently, active members of the fire brigade and armed guards. Hans was counting on that even if it was growing clear that he may have lost his way a bit among the political currents that had his country riven in conflict.

The armed guards, talented though they might be with the unruly human element, were unlikely to be equally effective deterrents to the consequences of stray perambulations of the physio-chemical universe beneath the timed direction of chains of events from afar. And the fire brigade was good at its trade once flames licked at ceilings—and could surely save the overall school as a whole—and not so effective before the initial spark or the first rising curl of accelerated smoke.

All Things Being Equal February 9, 1948

Dr. Petrov saw the first smudges of smoke on the northern horizon and went through his drill again as he gained upon the Jorco River bridge, several kilometers yet distant. He would park in his regular spot two blocks away from the school, assuming he could, would rush to first offer his stunned assistance to whatever security contingent that manned the cordoned line, and once rebuffed by those professionals, would retreat, confused and dismayed, a block back or more, semi-panicked, to stand back in a state of shock along with everyone else arriving for their own presumably regular days of school or vote counting, shape-shifting, or metastatic relaxation. To return to the scene of a crime was a beginner’s mistake, often the cardinal cause of discovery. But for Hans there was no choice. That did not make him any the less nervous, though he passed the test.

It was all great guns upon being rebuffed by the fire brigade commander who ordered him back, to let his men handle it. He retreated as planned to where a crowd stood back and buzzed with commentary, and he drew on his mask of shock and dismay, squeezing saline through tear ducts to squirt weirdly onto his cheeks. It was all going just like he had it planned, in fact. Imagine his surprise to turn upon the tap on his back shoulder to face Isadora Arias Cardenas de Zuniga, all dressed to the nines, smiling at him.

“Why you don’t look very surprised at all, Hans,” she ran her index finger along his chin and leaned toward him to touch his stiff lips with her pouty, painted ones. “Almost as if you were expecting me.”

“You’re dead!” he blanched, beads of perspiration rising from his hairline, their mouths bumping.

“Am I?” she grinned.

“And why are your eyes blue?”

Her left eye turned yellow, suddenly and she sighed loudly and broke into an awkward chuckle. “It’s so hard to hold,” she explained. “I can shift easy, Sugar Bacon, but to hold the two eyes the same color; it really takes a lot of concentration.”

“You mustn’t call me that; it was her pet name for me, not yours. Who are you? WHAT are you?”

“Her pet name?”

“Izzy, I helped to slide you into the crypt. You killed yourself with the Reina de la Noche. Why did you do that to us?”

“Oh, that was an accident,” she waved it away. “It’s a reliable abortifacient. Reina de la noche: you know that. I was not shooting for the big farewell. My hand just got away from me on the measure, I’m afraid. Dose is everything,” she shrugged, “as they keep on saying in post-mortem drug-overdose therapy sessions, on this side of the sigma verse.”

“Abortifacient?”

“How was I ever going to explain away the red hair, Dr. Petrov? I couldn’t be having your child; you know that.”

“Did I not have a right to know you were pregnant?”

“It would have been indecorous, darling,” she declined to reply, “a child between us. Don’t take it so personally. After all, look how much it wound up costing me!”

“Doctor Petrov,” came the voice of Caridad Fischel, “Ana Cristina! Look how awful this tragedy and the shame, the capital’s ballot security entrusted to our care!”

And just like that Izzy was no longer Izzy but Ana Cristina Durán all of a sudden, and Caridad Fischel perched sixteen hands high on a silver mare’s dressage saddle, a spirited two-year old. Dr. Petrov watched for a couple moments, but the apparition was so far holding onto the color and fixity of both of Ana Cristina’s auburn eyes.

“Gatilla,” Hans leaned into Durán to hiss.

Fischel’s mare, Reina, leaned across the distance separating them and sniffed the side of Petrov’s face and then bit his ear and drew blood, provoking Señorita Caridad Fischel into a shocked frenzy of horse-whipping and shrieking, which drew snorts of mare laughter and more prancing around the sidewalk, glares at Petrov first through her yellow eye and then through her blue one. Predators, like, say, human beings, have eyes in front of our faces and depend on stereo vision for the perception of depth that allows us to so easily kill our prey. Odd-toed ungulates are beasts cut from a different bolt of cloth. Being a horse, it was quite impossible for Reina to glare at Hans out of both eyes at the same time, though dearly she would have loved to do precisely that…all things being equal, that is.

“You know,” Ana Cristina looked up sternly into her professor’s eyes as Fischel managed to jerk Reina back into a compliant kind of impatient dressage back and forth between the sidewalk and the street tarmac, “I am not sure whether Reina really likes you or really dislikes you, Dr. Petrov, but I’m quite sure it’s one or the other.

“And why can’t it be both, you virginal witch?”

“Can’t have it both ways, Professor,” she smiled, touching his chin with the tip of her index finger.

“Oh, but I think I can, Señorita Durán. After all, every challenge is upon closer scrutiny merely one more opportunity in disguise.”

Finca Montes, San Ramón April 19, 1948

The tide rolled into the Figueres camp as news of his forces’ recapture of San Isidro was confirmed by two independent sources.

“Crush him,” would have been Petrov’s advice had he been among the war counsel of his heroes.

“Calderon is at your mercy,” glared Rufino Largaespada. “The terms are yours to set.””

“And if it were your decision to make, don Rufino, you would…”

“Crush him,” both Figures and his advisor said it simultaneously, the former an interrogative, the latter an exclamation.

They laughed.

“To prevail we must do him one better,” said Figueres. “We must accord him and his advisors, and the outgoing administration the respect they deserve, the respect the people will want to see them accorded.”

“We MUST undo the social guarantees, don Pepe.” Largaespada intruded to direct the dialog. “They are an end to industry, agriculture, commerce and trade, as we know them.”

“This is not a zero-sum game, don Rufino,” declaimed Alberto Martén Chavarrí, soon to be Figueres’s Finance Minister.

“And the people like the guarantees,” Largaespada had to admit, throwing himself into the arms of that six-hundred-pound gorilla walking around among them.

“In fact,” spoke up the economist, “they’re looking for even more guarantees than what they got from Calderón. I say we throw out a new socioeconomic political model entirely, one in which the capitalists and labor alike both have and eat their cakes and where the landed gentry and working class each boast gains.”

“But,” objected Rufino, “that is perpetual motion. It is denied by the laws of first-principle physics.”

Figueres stabbed top of the table and took the measure from their eyes of the men arrayed before him.

“NOT,” he declared, looking slowly around the room to compose himself. “Not if the funding comes from our foreign allies,” he declaimed, “eager to sink a stake in the greatest Latin American political experiment ever launched.”

Figueres watched the wheels turn behind Largaespada’s brow, tumblers falling one-by-one into favorable spots, the overall model taking on a form that was the opposite of anything rational and for that very reason one that brimmed with the possibility of longevity, perhaps permanence.

“We’re going to out-Calderon Calderon,” Don Rufino finally said.

Figueres grinned broadly and turned his palms upward toward the circle of men surrounding him.

“First, we shall abolish the military and decommission all forces—starting with my own—except for a civic guard of keepers of the peace, which you will command, Rufino, until the dust is settled. Next, we shall enact female suffrage across the land. We shall follow a national policy of neutrality and distance ourselves from direct interference with our autocratic brethren in Nicaragua and Panama and other points north and south. We shall improve upon the United States experimental constitutional federal republic with a true constitutional democracy, one person, one vote. We are NOT going to undo term limits.”

“And the social guarantees, don Pepe?” asked Alberto.

“We cannot take them away,” Figueres declared. “That ship has sailed.”

“Civil war all over again,” Largaespada suspected.

“The dashed expectations of a rising middle class,” warned Marten.

“We shall confirm the social guarantees and ratify a Constitution to the effect,” proclaimed Figueres. The moment that happens, I restore the constitutional order to the President-elect, Dr. Otilio Ulate. The ballot fire at the girl’s high school was an act of God—our hands are clean—though it certainly did not hurt our cause. We cannot undo the will of the nation that turned out in good faith at the polls to have their say on election day.”

“And,” don Pepe held his finger in the air lest anyone miss this most important point of all. “We shall start work immediately and achieve these goals within eighteen months of taking office.”

“When shall we schedule your inauguration, don Pepe?”

“Let’s get Leon Herrera in there instead as a transitional president from their own party, but” don Pepe smiled, “someone I can work with. How could any of them object? We don’t want to rain too hard all at once with our brand-new drops of National Liberation Party rain, now do we, Gentlemen?”

“How long, then?”

“Let’s give it three months,” Figueres decided. “And then eighteen months of reform before I return the presidency to Don Otilio.”

No one in the room suspected for even a second that he would relinquish power like he claimed he would, yet 21 months hence he would do just exactly that and set his nation on an international path that would keep it unique among all nations of the world for pretty much all the time it took until the first Nuclear Armageddon 45 years hence, and then, arguably, at least five millennium beyond that at a time in which the Tiquicia Empire extended from the Yucatan Peninsula through northwestern South America, well beyond the timeline of this (Costa Gothika’s) mere 1000-year documentary narrative.

The Metaverse Inauguration Party April, 1948

Whatever gatilla spirit it was that had one yellow and one blue eye was clearly fucking with our eager villain wannabe and reluctant antihero, the treacherous fascist apologist and intellectual libertine, Dr. Hans Alexis Petrov. It was a hot April night, the chance of rain not too much higher than Barstow’s and he settled on top-down for tonight’s little solo ride back and forth to the Presidential inauguration. Of course, the bitter blood between the Figueres and Calderón clans forbad the possibility of attendance of Don Rafael or Emilia or any blood-family member. Hans was dispatched as a kind of requisite envoy. Siotu fluttered her wings and scratched at the windshield with the tiny paws of her resplendent-quetzal incarnation, and Hans froze to admire the way her tail feathers fluttered down the glass, appearing to be both under her agency and subject to movements in the air. He thought about returning to the manor to supplicate a final time with Emilia to join him for this requisite pageantry. But that was cowardly. Weak. He knew she could not attend, and anyway this specter, this gatilla riding his shoulder—he was sure she was female—was his to contend with, not hers, perhaps of his very own making, even. Might as well man up to it.

“You are not going to make this very easy on me, are you?” Hans asked the creature through the glass.

The bird pushed against the invisible barrier to leap from the windshield into a fluttery night flight.

***

At the staircase beside where he turned the Packard over to a valet parking attendant, she appeared seated on top of the column of the first rise of stairs as a calico cat and looked down upon him with both eyes as he drew near her corner to turn and continue to the left to the second floor. She licked her paw as he passed by the corner landing and they took one another in, hardly ships in the night. At the top of the staircase, he turned to find her gone.

***

“Excuse me,” she bumped into him as he threaded the door onto the lawn and she stepped inside. She was a middle-aged black woman, this time, bedecked with evening wear and quick with a blue wink as she greeted him warmly through a Jamaican accent.

***

Speeches were still a while in coming, it appeared. A brass band played on the stage but did not drown out the conversations on the Presidential Lawn. Petrov repaired to the standing bar and leaned across to request fresco with guaro and turned to find Isadora’s widower facing him.

“Licenciado Zuniga,” he reached out in surprise to shake his rival’s hand.

“I know about you and Isadora,” Amancio replied, accepting the hand to shake with insufficient reluctance.

“I am sorry, Amancio,” Hans offered. “I cannot get her out of my mind. The why. I can’t shake it.”

“It makes little difference now,” Zuniga shrugged, tears streaming down his cheeks. “She killed herself, Hans. Why would she go and do a thing like that?”

***

Somehow a smile was not how she quite expected to be greeted by her husband at surprising him like this. Obviously, he would see it as manipulative, but she really had just changed her mind and was surely going to have to face the music when her siblings and parents were made aware of her attendance at tonight’s event. She was going to be in trouble not just with him, but even more so with them, but there was something about trouble that rang true to Emilia and made sense. It was not like she had never been in trouble before. What was the worse anyone could do? Give her the silence treatment for a day or two?

She held the ticket he had given her “in case she changed her mind.”

“Changed my mind,” she smiled, waving it in the air toward him as he approached to sit down, grinning widely, almost insanely.

“You don’t think I’m going to fall for it, do you?” he said. “What should I call you, anyway?”

“Hans, baby,” she frowned. “What’s got into you?”

“You got here so quickly.”

“I don’t like to be late, Butter-Ball.”

“At least you’re back to your own terms of endearment,” he glanced sidelong.

“Okay, yes, you guessed it,” she smirked. “I am not wearing underwear.”

“What is that?” he asked, startled.

“What is what?”

“That,” he points to the pulsing purse clenched between her thighs. “It’s moving. What do you have in there?”

“Oh,” she removes a velvet pouch from inside her handbag. “Oh…you mean the ‘Countess.’”

Countess was a hedgehog that stood on Emilia’s palm and gazed into Dr. Petrov’s eyes through a yellow eye on one side and a blue eye on the other and just far enough forward on its little rodential face to take him in with partial stereo vision to recognize him as 1.5 meters away, plus or minus 8%.

“How do you know her name is Countess?”

“It’s not,” Emilia replied. “That’s her nom de plume.”

“What do you want from me?” He asked the creature.

Largaespada approached the microphone, tapped on it, and began to warm the crowd. Countess stood on her hind legs and waved her head a bit to turn into a rat to drop and rebound from Emilia’s knee to the floor, where she scurried away and was lost within a flurry of shadow and motion.

“Ladies and Gentlemen,” the crystal vibrated under the microphone’s throbbing bass. “I give you the president-designate of the Republic of Costa Rica, Don José “Pepe” Figueres Ferrer.”

His fingers invading the slit in his wife’s skirt fabric, her thighs not yet willing to part beneath the gently plying digital wedges, he challenged her a final time. “You really are my wife, aren’t you? You’re no apparition. You are no specter! Tell me it’s true!”

“I thought you buried your wife a week ago,” Emilia replied. “Slid her into a crypt up in Santa Maria, or did I get that wrong? You probably have to let it go at some point. You can’t let it consume you. Just call this a little adventure; don’t get carried away and make more of it than it really is.”

She kneeled before him to extend her thoracic projection, her haunches rising from her kneel.

“Go on,” she said. “Climb on my back. Let’s go for a ride. What can it hurt?”

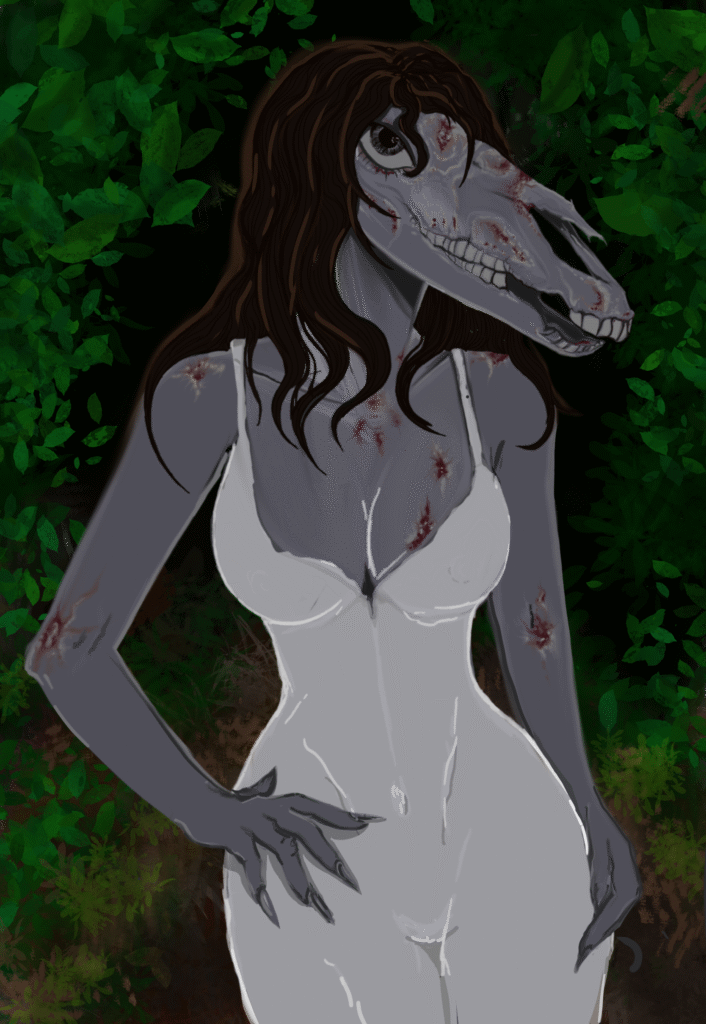

After lifting into the air and flying around a while, she turned a cadaverous glance back upon our antiheroic villain, parts of her skin peeling away to reveal an elongated and sharp snout of bleached bone and enlarged eyes that hovered inside the eye-sockets of the creature’s skull.

“You know we’re a long way up here, right?” She puts the thought in his head.

“You Pegasus, me Bellerophon,” he returns the favor. “Nothing more than that.”

“Oh please, Hans. It’s just you and me up here.”

“And the world below.”

“No, my love. Up here, it is just you and me.”

“Not even a moon with which to share this great adventure,” he again resists.

“Are you safe from such heights, Bellerophon? You wouldn’t wanna fall off my back now, would you?”

“No, probably not.”

“It’s a long way down.”

“It’s not THAT far.”

“Oh, it’s far enough, you’ll have to admit, Sugar Bacon…I mean…Butter Ball.”

“I admit it’s true.”

“What if I frighten you so badly that you jump off my back to escape me?”

“You would not do that to me.”

“Maybe I would not,” she shimmied. “Maybe I would.”

“Maybe you can’t scare me,” he says.

“Still, here we are,” she replies with a shrug that carries through her withers to make his prostrate throb.

“Well, I am not overwhelmed with choices up here,” he allows.

“We ALWAYS have choices, Dr. Petrov.”

“You must now bite me deeply,” he relents. “You must mark me and shame me. It is foretold.”

She shrugged through the cordoned muscles of her back. He gripped her rib cage and clung to her wings rising along a thermal up the slope of the Cerro de la Muerte bound in the direction that their home lay somewhere, hewn from the forest. She whinnied and shuddered with the ecstasy of the moment.

“Best get on with it, dear.”