Cañaza Saturday 6:00 p.m.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way.

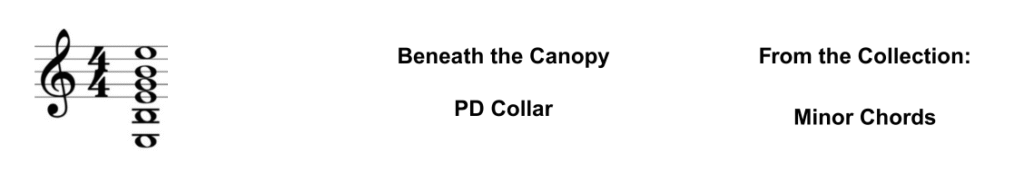

Danilo Araya was back from swinging a bad deal at the mill but stopped short at the sight of the black Montero in his driveway. With nothing left but to face the dogs, he pulled in and around the waiting car onto the grass. He took a few breaths, pulled the rear-view toward him, smoothed down his collar, and mustered a smile. He exhaled and stepped out, putting a hop in his step.

“Gentlemen.” The two men stood from around the table to shake his hand. They did not return his smile. “Baby,” he winked, “why don’t you be a doll and step over to Lucinda’s for a bit?”

The intruders looked at one another. The small one nodded, and she left. “Hey, I have till next Friday,” Danilo pointed out. “What’s up?”

“Change of plans.”

“Well I only have one and a half now,” he said. “I was counting on a million in the next couple days on a wood deal to round out the note.”

The little one studied it over. “This has reached its limit, Chapín,” he said.

“Our agreement was for Friday; the last guy and I shook on it with Don Javier on the horn. A deal’s a deal,” he said.

“Let’s see the dough.”

He unlocked a filing cabinet on his desk and produced an envelope and laid it on the table.

The man counted the one hundred and fifty bank notes and folded the wad and put it in his shirt pocket. “You’ve got till Saturday week to pay the balance. Three and a half million.”

“But the deal was a full month for the final payment. Don Javier agreed to it.” “The deal has changed. One week from Saturday. That’s all you get.”

They stood to leave. The big one stopped at the doorway and turned. “You better have it, Araya. Twelve noon. That will be our last trip over on this business, one way or the other. Got it?”

“Yeah,” Danilo said. “I got it.”

San Miguel de Cañaza Sunday 10:00 a.m

“The dogs,” Andrés said. “Where’d they get off to?”

“It’s our neighbor up ahead,” his father said. “She’s laying for us.” “Why would she do that, Pops?”

“Set on lecturing me again, I figure.”

“Why can’t she mind her own business, Pops?” “Not her way, I guess. Trying to save the world.”

Andrés shuffled under his load. Day was full on them, but in the understory it was dark and cool, even in the morning before the clouds moved in to kick up the breeze and bring on the rain. He carried the two field-dressed agoutis hanging from the rifle, one from the barrel, the other from the stock, the .22 balanced across his shoulders. Never one to waste rounds, Pop had shot twice and now drew up the rear as Andrés set the pace, the dogs somewhere up ahead, out of sight.

They talked freely, unconcerned with stealth on their way home, their voices low out of habit. Their feet could not tell the difference between going and coming and passed across the decaying humus silently.

Sylván Montes had never been sure of his age, but he called himself seventy-two. He had twelve children from four wives. The last one—Andrés’s mother—died from a fer de lance that bit her in the outhouse ten years back, and he’d raised the boy up himself since. From a vantage point where he scanned the saddle below and rise beyond for sign, he signaled for quiet. Half way up and off to the right he saw one of the hounds bedded down still and devised another off to the right and then a third, flopped out on the ground, moving their tails. He figured the fourth was behind the tree with the gringa. He imagined her sitting cross- legged, her back to the trunk out of sight to him, Santos with his eyes closed getting his head stroked in her lap. The old man pointed down across the boy’s shoulder to show him where she was laid up.

“Bet she’s picking off ticks,” the old man whispered.

“Why don’t we double around down the hollow and up yonder crick, Pops? We can come up on her from the far side where she ain’t expecting us.”

“Nah, she don’t mean no harm, boy, sides the dogs’d raise us anyway.” “Our own dogs?”

“They ain’t trained up on spy craft, Son. I ain’t got ‘em past running game and droving cattle every once in a while.”

At the base of the saddle, Sylván whistled up the hounds and waited till they bounded down the trail to swarm him with tails wagging, eager for whatever was next. The old man had them walk ahead, but at his pace. The woman stepped from behind a manglillo and stood in the trail, her arms crossed, her brow furrowed, a machete tied to her waste, all bent, it appeared, on letting her man side out. The dogs broke to rub against her like cats, their tails wagging, and they looked up at her and then back down at their master.

“Doña Carmela,” he smiled broadly as the boy stepped aside for him to take the lead. “What a pleasant surprise.” He turned his palms to the sky. “Beautiful day, don’t you think?”

“You are hunting on my land, Sylván. We have talked about this.” Her accent made her hard to understand, but he’d gotten used to it. It didn’t much matter; he knew what she was going to say anyway.

“No, no,” he shook his head and smiled. “We took these on the other side of the ridge, in Camilo’s finca, nearly to the Park.”

“This is my land,” she gestured to her left, “and you’re poaching. Those are dead

tepezcuintles you are carrying. Are you off to sell them?”

The boy lifted the loop from the barrel and held out the gutted carcass to the woman. “They don’t call Pops Tepe for nothing,” he offered. “If you want, you can have this one here for only ten thousand colones. That’s a third of what he’d bring in Pérez!”

“She does not want a tepezcuintle,” the old man chided gruffly. “She is one that does not eat animals that contain meat.” He raised his eyebrows toward her. “Only fish and chickens and things like that, right, Doña Carmela?”

She rolled her eyes.

Andrés looked at his father and again at the gringa, shrugged, and restrung the game and balanced the rifle again across his shoulders.

“Don Sylván,” the woman softened her tone and dropped her crossed arms to plant her hands on her hips. “These animals are protected. What you are doing is illegal. You’ll empty the forest of life. Is that what you want?”

The old man’s attention hardened upon her.

“Now you look here, daughter. This,” he gestured to his left, is my land. I have told you before, and I will tell you again. I don’t need some smarty pants gringa to come tell me what I may not do on my soil in my country. You come here on high horses to save the forest that birthed me, and you don’t understand it, and you don’t understand me, and you don’t understand my people. You come to tell us that we cannot cut wood to build our homes or to sell in town to buy rice and beans. You tell us that we cannot mine gold from the rivers because it will muddy the water and hurt the tadpoles and crawdads and other things of no importance. You tell me I cannot feed myself and my boy with this rifle. What is it that you would have me do in order to eat? Take tourists on walks, depend on their generosity like those young dandies from town?”

“So you take your hardship out on . . . these creatures?” She gestured at Andrés’s load.

“You would like for me to sit in my rancho and starve?” “Of course not; you know that.”

“Maybe I should go and beg in the streets of Puerto Jiménez? Go cry to my grown children with their own struggles to take me in or send me money? Go find an old folk’s home in Villa Neilly or San Vito to take me in? What do you want from me?”

“What if everybody went out and killed the agoutis, peccaries, and tapirs, how long do you think it would be before there would be none left?”

“But everybody does not kill them,” Tepe replied rationally. “And there are many, many animals in the forest. Why, there are not enough tigres left to control the peccaries, so we are overrun with them, these days.” He paused for a moment to conclude. “You should think of me as just a different kind of jaguar, that’s all.”

“Bullshit, this forest is not overrun with anything but poachers, miners, and illegal loggers, and you’re no tigre, old man; you’re a poacher.”

“You keep talking about this conservation group coming to buy me and the neighbors out,” he reminded her. “I have five of us in—650 hectares—ready for you and your supposed buyers. I have done what you asked, but nobody comes with any money, and it is all talk, and meanwhile I still have to eat.”

“You know the conditions. Look, I got word Friday that the ACOSA application was approved, just a question of the paperwork to catch up with the decision, a couple weeks. And my title is due out any day now. It’s not talk; it’s a sure deal once those two things are set. I would never lie, least to you.”

“If it’s a sure deal then a deposit of say, ten million, would be a fair sign of good faith,” Montes pointed out. “You have given fifty million so far to that Danilo Araya for Manuel Sanchez’s old place. What’s a little ten million for me?”

“If I had it I would.”

“Don Manuel lived here with the missus next to me for sixty years the same as I live now. That’s half a century, little miss. We hunted together years before you were a hunger in your father’s loins, me and el Viejo Manuel. And we partnered up on a few gold claims through the years also, and built our ranchos from the wood of our own land. Give me just ten million, and I too will let you owe me the balance.” He let it hang for a moment. “But until you do, please don’t lecture me about hunting.”

“Selling the meat sustains a market, Tepe, and the gluttony of Pérez alone will empty this forest. You don’t want that, I know you don’t. But that’s what you are causing to happen. Eat these animals yourself; don’t sell them! The world has changed don Sylván, and you must change with it.”

“Let’s go, boy. No sense talking when no one’s listening.” He pushed forward and when the woman would not move to let him by on the path he stepped around her.

“I will go to MINAET,” she called up the hill after him. “I will file a denuncia

against you.”

“You have already been to MINAET,” he called back over his shoulder. “Let them come back and lecture me. File your denuncias. I don’t care. Let them arrest me if they want. I’m not going anywhere. You want to stop me, go back home and bring out that pistol you have threatened others with and come shoot me. The saínos will sing your praises, doña Carmela. They will love you, their savior.”

She watched him retreat up the ridgeline trail and stood as the silence enveloped her, one foot on her land, the other on his, to glare at his retreat. When he turned to her after fifty or so paces, she was sure she had willed it. His armor could be dented. She just had to keep after him. That and close out the Green Leaf deal and get him off to Perez to bounce great-grandchildren on his knee, as he liked to put it, and eat Sunday cakes in a concrete house with indoor plumbing.

“You have a nice day, Doña Carmelita. You come down to the house sometime for some coffee. I have a milpa nearing harvest, and I will fry you a fat chorreada dulce. Or. . . you like something stronger, I got a little aguardiente hidden under the floorboards. For you, I will take it out and we will drink the forest’s health together.”

Cañaza Sunday 6:00 p.m

The onions and sweet peppers hit the oil with an angry sizzle, and Maribel Sanchez de Araya winced over her shoulder with a stab of pain at her husband and stirred the pan with one hand and reached down a bag of rice from the cupboard with the other. Along with all his other ventures, she was wary of this wood business. She had married a handsome, sharp-dressing, sweet-talker and now had four kids with him—and counting—but had given up on her dream of him turning into a respectable community leader with a decent job as a manager for Palma Tica or running a little pulpería or some cabinas or a couple taxis or any other type of honorable work with a regular paycheck and hours. Instead it was these stories over the cell phone with strange men, creditors always hovering over them, suspicious looks from the neighbors. Once in a blue moon there was a bit of money to settle their account with the pulpería and catch up on utilities to buy a day or two of peace, rarely a Sunday at the beach with the kids, or a Saturday night dance with the kids at her mother’s, until he disappeared off to the cockpit for to drag back home dirty, sweaty, hung-dog, and mean. The pain in her abdomen flared up again as she poured water into the sautéed rice and vegetables. None of the antacids and stuff they gave her at the clinic seemed to make any difference.

“Don Fernando,” her husband cooed into the cell phone, “you worry too much. I told you it’s all there . . . si, señor, twelve thousand pulgadas, blocked up and on the mountainside in San Miguel. It’s these rains, Don Fernando. With the river swollen we can’t get it to the mill. Just yesterday we got a backhoe stuck, Don Fernando, a backhoe . . . well sure we have a tractor . . . well, I don’t know why he would say he hasn’t been paid, why just yesterday . . . easy, easy . . . calm down. Anyway, that’s my business . . . yes even with a tractor or a backhoe or a team of oxen or goddamned D-8 Caterpillar for that matter, it would make little difference with the Rincón out of its banks . . . this is an act of God, Don Fernando.”

Danilo Araya sighed and looked up at his wife with a humorless grin. The things he had to put up with to turn a lousy few rojos. “No, no, sir, heaven forbid, we certainly cannot move it to river’s edge and wait. This wood, you know good and well, sir, does not have all the legal . . . you just have to be patient. We can’t move it a centimeter until we can haul it all the way to the mill in one shot.”

He held the phone away from his ear and used his wife as an audience to roll his head back and forth to mock the disjointed voice spewing angry static from the cell phone into the kitchen air. Maribel turned back to the stove to grimace in private with a new stab of pain. The water that swelled her eyes came from a hurt, however, quite different from the physical pain that it exacerbated.

“Oh, I understand, Don Fernando, and I assure you, this is only the highest quality cortesa, and for one thousand six hundred per pulgada, this is practically a gift. You know it’s going for twenty-five hundred in Pérez, of course you know . . . “ “Yes sir, of course, you made a deposit of three and a half million, no worries . . . but Don Fernando, don’t forget that this is special wood, not fully permitted, so don’t talk to me about law suits or I won’t be able to respond for the wood or the money . . . Don Fernando, there is no need to get overworked about this; it is only because of the rains. In a couple of days the river will go down and we’ll get your wood across and to the mill, and once it is there, we have a permit to cover it, and you’ll have it milled and planed to the millimeter and delivered to your construction site two days later, tops three . . .” He rolled his eyes and winked as his wife turned to plead with her eyes and brought the phone back to his ear.

“Say, I can’t hear you, Don Fernando, I’m up in the woods here above Cañaza, and the coverage seems to . . . you’re breaking up . . . I’ll call you first thing in the morning.” He pushed a button on the phone and then turned it off altogether and rubbed his hands briskly together.

“Dani,” she said gently as the rice came to a boil behind her and the skillet heated over an open flame. “Baby I can’t go on like this; this is no way to live, sweetheart. We have babies, little sweet children in pre-kinder and grade school, and there are uniforms and books, and your mother will not be able to live on her own for much longer, and look at us . . . “

“What’s gotten into you, Mami?”

I would not care much how people look at me in the street if had at least a decent dress and the kids new shoes or if we had a washing machines and I weren’t wearing my fingers raw on the pila out back. I want to be able to eat shrimp or lomito every once in awhile instead of this.” She pealed the thin bistec slices away from one another, and they separated reticently, strings of nappy mucous snapping back to the thin slices of separated meat before she laid them on the cutting board and turned away from him to begin pounding them with a mallet.

“Ay Mamita Mimi, my baby,” he rose to embrace her from behind. He wrapped his arms about her waist and kissed her neck and rubbed himself against her behind. “The way you handle that mallet and slice those onions transports me, my queen, perhaps we should duck in the bedroom while the kids are out playing and put all of these crazy things out of your head. Turn the stove off, my pet, just a minute is all it will take.”

She shook him off and whirled upon him furiously, her mallet raised. “Pull that thing out,” she commanded him. “Right now!”

He smiled and withdrew to his seat and winked. “You play so rough,” he said. “Pour me a cup of coffee, why doncha, Sweetheart.”

She set the cup down to slosh on the table. “Sugar it with that paja that spills out of your mouth, why doncha, Sweetheart!”

They stared at each other frozen in their stances, the meat sizzling innocently in the pan, and Danilo squeezed a bit of water to fill his eyes.

“Baby,” he said low. “What is it, darling?” he asked gently. She glared at him.

“Is it the gastritis acting up again, honey?” She cocked her head.

“I can’t stand that you have to bare that. I must take you at once to a specialist in San Jose!”

She threw the onions in on the sizzling meat and turned around, knife in hand.

“With what money, Dani, Sweetie? Look at us, you don’t work, and I have the kids to run me ragged all day, living here. In this hovel . . . ”

“Baby this is a concrete house. This is no wood shack in the hills. This is no rancho. This ain’t no hovel.”

“Dani, It is a tiny little sweatbox, baby.” “It has indoor plumbing.”

“There’s six of us. One bathroom? Please, Papi.”

“And what do you mean I don’t work? I’m working now, Mimi, what do you want from me? To work for a day rate? I am a businessman, not a laborer. I have a brain, and I have the clothes that a businessman needs, a car, the basics to do business. It takes money to make money. It’s cash flow, Mimi. What, you want me to go down and work construction on the new supermarket in Jimenez? I could, you know. Or get Alvaro to hire me on as stock boy in the almacén or yard man at La Costa? I could do that. And make fifteen thousand lousy rojos a day, tops, no more than a half a million a month. This one deal with Don Fernando will net us a cool two million for two weeks of nothing more than making calls and intermediating.”

“Making calls to tell lies,” she groused. “And intermediating other people’s money into your pockets!”

“It all spends the same, baby, what’s the matter with you?”

She speared a piece of meat and flipped it and a cloud of aerosols spattered angrily.

“Fifty million colones!” she screeched. “My inheritance. My parents’ finca. Fifty million colones. And you’ve blown it all in two short years.”

Danilo lowered his eyes and dredged up a look of sober regret.“Investments don’t always work out.” he said.

“What investment?” she began to cry. “You call drugs an investment?”

“Look,” he cut her short; “if that deal had worked out, we would be sitting on a couple hundred million and be well on the way to being set for life; it was worth the risk.”

“But they were maras, Dani,” she sobbed. “It’s a wonder they didn’t kill you. And then that crazy business with the gold and all those crooks up at Cerro de Oro . . . you threw so much away and on nothing.”

“I can’t help it that the old bastard had a stroke and died in his sleep. Again, baby, that claim is now pulling in ten million a month.”

“For his sons,” she screeched. “And bankrolled on my inheritance!” She stamped the floor with her foot and winced from the pain that shot through her abdomen.

“I couldn’t have known he was going to drop dead, baby. It was bad luck, that’s all.”

“You could have drawn up a contract, all legal, and protected the investment. I told you to go see Pecas and have him draw up a paper. I told you.”

“There’s nothing to be done about it now. It was bad luck, that’s all.”

“And now this talk of borrowing money to buy sport fishing boats . . . what do you know about sport fishing, Danilo?”

“Look, nobody knows anything until they do something. There’s a lot of money in sailfish and marlin. These gringos pay big money.”

“And all the money you’ve thrown away gambling, Dani, frittering our children’s welfare on those filthy animals! And who were those two men, yesterday? What did they want? They looked like gangsters.”

“Enough!” he shouted.

She jumped at the outburst and removed the meat fussily onto a platter and stopped when it welled up in her and covered her eyes to quietly cry. When he encircled her from behind this time, he was gentle and corralled doves to tether with ribbons to his tongue.

“You are my queen, baby, and I will make everything right for you. I will buy you the Tower of Eiffel, my pet,” he cooed into her ear. “And I will take you on a tour of the Liberty Statue in Washington. I will fatten you on jumbo shrimp, conch ceviche, and suckling pig, my little cotinga. Everybody will turn when you walk down the street and wish they could walk in your shoes.”

“Oh Danilo . . . I don’t need all that; I just want to have a decent life and be respectable to our neighbors.”

“Look,” he turned her around and widened his eyes before kissing her forehead and both cheeks then each eyelid in succession. He looked at her again and touched her lips gently with his own. “Doña Carmela still has a balance of twenty- five million due in six short months. I swear that I will not touch it for anything with any risk. It will be your savings.”

She looked up at him and stilled her sobs and felt the pain in her abdomen recede into a reticent well of hope, dependence, and a stirring in her womb, a tentative hunger that dared to exhale.

“I swear it, okay, Mimi?”

“Okay, Dani,” she ventured a timorous smile and kissed him with passive lips, her limbs slack. “I believe you.”

“And . . .“ He cocked his head and held her eyes with his; “. . . and I think I know how to squeeze another twenty-five million out of her to boot . . . something I have been working on.“

“Those gringos, they’re all so rich,” she reminded him. “And the land is worth far more than the price that you agreed to. That was two years ago.”

“And times have changed,” he agreed.

“And interest. To pay in payments over three years is the same as a loan, and for a loan, interest must be paid.”

“Miguel Arce is charging 5% per month,” he said.

“You have not borrowed money from don Miguel,” she looked up, aghast.

“Oh no,” he lied, chuckling. “Oh hardly; I would never borrow money on those terms. I was just saying that you are right, that there is big money in carrying a loan, especially when it is for a foreigner, of all people.”

“You scared me there for a minute, Papi,” she smiled, looking down, thinking of her mother, God rest her soul, and how she would have been shocked at how freely Mimi spoke to her husband, questioning his decisions sometimes, getting involved in the planning of the finances, involving herself in the things of men where she did not belong.

“Baby, go call the kids,” she smiled weakly. “Dinner’s ready.”

Dawn came to the forest in stages that Karmel Greene allowed nightly to punctuate her waking. Before it began, in the black of night beyond the gentle patter of rain, the fragrance of orchids filling the air, animals moved around outside to forage and hunt. Around three-thirty in the morning, everything went dead, and even the solitary chirps of frogs ceased. The animals returned to their burrows. The orchids folded their dewy petals up into a ball. The amphibians settled against something wet and cold, the heavens stilled, and silence was the first morning flower to blossom. It was at this stage of the morning that Karmel dreamed the most vividly, dreams that she sought later to recall over coffee on the porch as she would wait for the sun to break over the jagged peaks of distant mountains.

The deepest blackest quietest part of night, the first stage of her morning, was broken daily by a single twitter from that bird that she imagined getting the worm, a twitter that would rise at first in a tentative trill from the small clearing around her cabin and progress to a more confident clutch of chirps that in the imagined stretching of wings broke into what could finally be called nothing less than song. She awakened to the clarion of the first solitary voice piped through a darkness yet unbreached by coming day and fell immediately back into a fecund sleep.

The third stage of morning was launched by the howler monkeys, which awakened at around 4:30. If they were far away, only the basso roars would reach into her near-surface dreams to speed her on through the remnants of her night. But if they happened to nest in one of the trees near the edge of the clearing, then she would awaken to the gentle clicking of their vocal chords that prefaced their monstrous howls, weird sounds that you had to be very near them to actually hear. To her they were the sounds of skeletons dancing on their knees as they banged their rib bones like marimbas with their own tibias. But on this particular morning the closest troop was far away, and she allowed its howls to fold roughly into her dreams without ever raising her from the pool in which her shallow breath rose and fell. She liked to remind her gal pals that the howlers’ role in life was to announce to the world that it was time to wake up and make love. But since Samuel had left—or since she had managed to run him off—she tried with scant success to walk back that association. After ten minutes or so of the howlers’ chorus, a faint blush pushed at the ink of the horizon to fondle the night’s girdle, and Karmel awakened to lie in bed and chart her day. She rose to make coffee and donned a slip left over from the wine-and-roses days to monitor the lifting of the darkness and the descent of the day.

She looked down from the porch swing Samuel had built over the canopy of old growth forest that reached up the mountain. Beyond the shadowy blues and greens of an awakening forest, the alluvial plane below swept gently in penumbral chartreuse toward the coast. There were cattle ranches, rice farms, palm oil plantations, copses of secondary forest, and small houses with thin ribbons of wood smoke rising from hearths scattered across the land. The plane was broken by the sinuous weave of rivers working their way to the gulf. From her porch she could see the Barrigones to the north and the Sábalo to the south. Their meandering traces were inked into the peninsular canvas by remaining stands of old growth, now highways for the monkeys to descend by morning to feed on the fruit trees of the plains. But farther to the north and south were the gold-bearing Tigre, Agujas, Conte, Terrones, and Rincon, rivers untamed by bridges until 1991. The gulf was still and black, the mainland across the water shrouded in clouds. The near shore was lined with mangroves that thickened to swamps in the estuaries that graded from water to land. Beyond the gulf, the coastal mountains rose vertically from the sea as deep green bluffs. Beyond their tops a second row of higher mountains in the distance was a lighter shade of green, and beyond those lay a ribbon of lavender cordillera visible only on clear days like today that were the Talamanca Mountains, the first line of defense against the coming sun. This spine of Central America, she was sure, must be as wild and virgin as the Osa inland to her back—more so even—and she liked to imagine herself perched upon the highest peak that she could see over there. She was certain that on a day as clear as today she would be able from that promontory to see both the Caribbean to the east and the Pacific to the west. One day, she liked to imagine, one day she would find that peak and camp there night after night until a dawn like today’s that would let her look out upon both oceans. Making its appearance, finally, like a flaming spear hurled from her favorite horizon, the sun wiped from the rising land the misty grays and dusky blues and murky greens to leave every color transcendent and raise the contours of the land into a three-dimensional grid. With the sun’s appearance, a breeze lifted from the lowlands and swept up the mountain slope and lifted her bangs and spirits and left a smile upon her face.

“Buenos Dias, Karma.” Her staff of four campesinas arrived on foot up the two- track drive, red clay stains high on their rubber boots. She greeted them by name as they made their way to the shop in back to get the day’s work started. She poured herself another cup of coffee before wandering around back to look in on the startup of another day of chocolate production. Today they were husking the forty-five kilos of cacao seeds that they had had roasted yesterday following Day One’s harvest and Day Two’s pulping. Once the gals were settled into the routine, she returned to cut onions and peppers for the gallo pinto to get the breakfast underway that they sat down to share daily at eight.

It wasn’t their fault that they were trained to hunt, and Montes’s dogs generally paid her a visit around this time of the morning when he didn’t have them off in the mountains. Unlike back at their real home, she encouraged them onto her porch, and all four were laying there when the sound of a motor on the road came into hearing and they raised their heads in its direction. She was working on the layout for a marketing brochure for her line of boutique chocolates and expecting Barb, but the sound wasn’t a quad, and she took her reading glasses off and allowed her face to set into a frown as she worked her way through her mental inventory to settle on the identity of that particular motor. She decided against fetching her pistol. He wasn’t a threat and it wouldn’t be right to just have it out to make a point. The hounds began to growl.

When Araya’s Samurai rounded the bend and came into the clearing, they boiled off the porch, ears lain back, to swarm the car and snarl. She allowed herself a smile as the glass on the driver’s side went up and Chapín cut the ignition and sat looking at her from inside the vehicle, hemmed in by the dogs. He lifted his palms toward her.

She looked at him a good long while and called the dogs off. They quieted and retreated to the porch to gather round her to sit and watch the visitor.

“What’s the matter, Chapín,” she called out as the driver set one foot cautiously on the ground and hesitantly got all the way out and eased his way closer, leaving the door open. “Ain’t afraid of a few dogs, are you?”

“Them’s Montes’s dogs, right?” he asked, putting a friendly side to his voice.

“They stay with him mostly,” she allowed. “I like to think they belong to themselves, like every living thing.”

“What about cattle?” he asked. “Do cattle belong to themselves?” “What do you want, Chapín? What are you doing up here?”

“Paying my respects,” he smiled. “Maybe buy a little chocolate to take home to Mimi for a surprise.”

“You can get that in town from any number of stores; I only sell wholesale from up here. You know that.”

“I hear you’re putting together a big land deal,” he said.

She made no move to rise from her chair, and the dogs watched the visitor attentively, and he did not stray from where he stood leaning against the hood of his car, distances measured.

“Can’t always trust what you hear,” she replied. “You know how it is with rumors.”

“Yes ma’am, Doña Carmela,” he replied, smiling. “I know how it is. Still, rumors, however exaggerated, tend to always have some basis in fact. Maybe we can put our heads together on this; two’s better than one, they say.”

“No thank you; one land deal with you in one lifetime is plenty for me. What do you want, Chapín? What are you doing up here?”

Danilo chuckled. He doffed his Panama and curled the corners of his mouth even higher. “Well, speaking of which; that’s why I’m here, mostly, we gotta talk about our agreement.” He cocked his head to put his sales cap on for this challenging assignment.

“What about it?”

“We need to renegotiate terms a bit. There have been some changes in circumstances.”

“What are you talking about?”

“That balance that’s due. I need at least a quarter of it now—or as soon as you can come up with it, next week at the latest—me and Mimi have some accounts we have to settle.”

“Tough shit. The note comes due in December, and that’s when you’ll get your money.”

“Well, I think it will be in everyone’s interest to discuss this amicably . . . “ “There’s nothing to discuss.”

“Well, if you are not able to come up with at least five million now, we can settle on doubling the final payment. I can give you another six months to settle.”

“What?”

“That way, me and the missus can take out a loan to cover our immediate needs without having to trouble you further.”

“Are you smoking crack, Chapín? Why would I do that?”

“Well, if you won’t worth with us on this, we’ll have to put the finca up as collateral for the loan. And if we do that, then the bank will have a lien, so come December, we won’t be able to sign it over to you, not clean anyways . . . “

“Wait a minute.”

“I’d hate for something like this to get in the way of your land deal. Course if you hold back on the final payment in December because the title is compromised,then that would be a default . . .” Chapín shrugged his shoulders to let her do the math.

Karmel studied him closely.

“And you have fifty million sunk into it and would surely not want to risk your equity, all from being unwilling to work out this little problem now.”

“I want you off my land right now.”

The tone of her voice set the pack of dogs to snarling, their ears lain back, and Araya took a step back.

“Doña Karma, there’s no need to get hostile about this. It’s not a big thing, a few million colones to tide us over, a gesture of good faith. And this is not your land. Not yet it’s not. You haven’t finished paying for it.”

“Get out,” she barked, causing Chapín to jump and the dogs to boil off the porch.

He gained the safety of his car, and she called the dogs back off him, and he rolled the window down half way.

“Perhaps I got off on the wrong foot,” he said, producing a facile smile; “I didn’t mean to seem pushy. It’s not any great difference for you to pay us a part now. It means less to pay later.”

“A deal’s a deal.”

“It is going to complicate things to get the bank involved. And you know of course that my nephew is well placed there, loan officer and all; he’s already assured me they can put it together. It’s likely to complicate the closing if you leave me no choice. I’d really prefer to keep it all clean and simple. All I need is five little million.”

“Tell your wife if I catch you on my property again, I will shoot you.” Chapín shook his head slowly before turning the ignition.

After the noise of the motor faded she drew the dogs around her and loved on them. On cue they looked up over through the woods in the direction of Sylván’s place and then up at her. “Go on, then,” she told them. “Get on home; Daddy’s wondering where you’ve gotten off to.”

They bounded off the porch and set off baying through the clearing and into the forest.

Puerto Jiménez Monday 9:30 a.m

Few things and even fewer people could dent the cheer that Diego Bonamérito wore to work every day along with his business suit. His uncle Danilo was one of those things and one of those people. When he looked up from the loan application package to see his uncle between the two sliding security doors of the bank’s entrance, he knew Uncle was not there to check his balance. Their eyes met, and Diego swallowed, put on a smile, and went to receive him.

Diego had started off after finishing his bachelor’s in accounting at Paso Canoas. He spent six months training in San José and Puerto Jiménez and put in two years as a teller. He leapfrogged the colleague he had trained under to the teller supervisor position when his predecessor was fired over something and worked a year in that thankless post. He applied for a transfer to plataforma and the chance to work directly with clients again. The brass agreed that his interpersonal skills sufficiently exceeded his valued attention to detail to grant him the transfer. He liked attending commercial clients, mostly for the variety, and was not ready after a year for his next move but allowed himself to be trundled off again to Chepe for training, this time in credit cards. He worked as the commercial credit card liaison officer for another two years and would have been happy to continue in that capacity. But his sunny disposition, attention to detail, and popularity among his subordinates, superiors, and peers alike had escaped no one’s attention, least of all the Southern Zone regional manager, who pulled him back up to San José for more training, this time in loans, and called him up on that occasion to his fifteenth floor office to explain the great expectations they all had in young Diego. Self-confidence was no stranger to him, and he acquitted himself admirably and with a modesty that reaffirmed the Regional Manager’s self-professed acumen for human resources. Diego knew now to politely take on each new job with a smile, that they were all temporary, and that he was being groomed for the top. They were rounding out his edges, and a few months away from his thirtieth birthday, he expected to be tapped for branch manager somewhere before he turned thirty-five, a good five to ten years ahead of the curve. He would not even have to go out of his way to get there; all he had to do was stay steady and show up on time well-groomed, wear the smile that came naturally, and keep doing his job, whatever it happened to be.

Things had always gone Diego’s way. He was deferential toward those that were not doing as well as he and gregarious toward those better off. He had just paid cash for a nice half-hectare lot on the edge of town and had a late model Daihatsu Terios with only eight more payments to go. In less than a year he would have the money to build a little house. He had youth, health, smarts, and good looks. He had placed second in last year’s Lapa Rios marathon and had a beautiful blond American girlfriend. His nickname was Galán.

“Hey Uncle Danilo,” he smiled. “Come, come, let me show you my new office!”

His visitor stepped in gingerly, bringing with him an unpleasant reek of cigarette smoke. He doffed his Panama to look around appreciatively at the glass partitions with their frosted trim and the framed documents hanging on the wall in back. Diplomas. Certificates of Achievement. A photograph of Diego shaking hands with the former President of the Republic. The desk was pressboard with simulated-wood laminate. A bookshelf against one wall had a row of binders neatly lined on the bottom shelf, titles printed on the spines. A blown glass paperweight and a mineral specimen sat on top. A flat screen monitor faced him on one side of his desk, and two manila files were stacked neatly on the other. Diego closed the open file and placed it on the stack. Beside the monitor was a hinged frame. Danilo turned it around: his sister-in-law—Galán’s mom—on the right and a blond woman on the left.

“This your girlfriend? The gringa?”

“Yes sir. Her name is Barbara Salazar. But don’t let the surname fool you. The only thing Latina about her is her perennial tardiness.”

They chuckled and Danilo set the frame back in its place. The nameplate on the outer edge of the desk had bold white text engraved into plastic with simulated wood grain that matched that of the desk, held in a shiny brass holder. It read:

DIEGO BONAMERITO ARAYA

Préstamos Comerciales

“You must be doing something right around here, Galán. This is the nicest office in the building.”

“Oh, no, Uncle,” he grinned. “In back there are nicer ones. Trust me. How is Aunt Mimi, Uncle? And my little cousins? I hear Danilo Junior is turning into quite the little striker.”

“Mimi struggles with her gastritis but stays strong, and the kids are great, and yes, Lillo scores at least one goal every match. Let me get down to it, Nephew; you’re a busy man.”

“By all means. How may I help you, Uncle?”

“You may not be aware,” Danilo began, “but the gringos with that big walled compound in Sándalo? You know who I mean? Well they’re selling their sport fishing business, two boats, gear, moorings, office lease, corporation, permits and licenses, everything. Lock, stock, and barrel.”

“I heard about that. Selling that compound as well. And some property they have in La Balsa. Clearing out.”

“Well, I don’t know about their real estate,” his uncle grinned, “but I have looked closely into their sport fishing operation, and the boats alone are worth twice what they’re asking for everything.”

“Seventy-five million, right?”

“Asking. Reliable sources say they’ll take sixty.”

Diego lifted his leg and rested his calf on the corner of his desk and studied the shine of his shoe leather. He looked up and settled his chin between his thumb and index finger, his elbow grounded on the armrest. Cold air blew down from the air-conditioning duct and played with a loose lock of his hair, which rose and fell inside the sterile office.

“I got a partner that’s got thirty. Now all I have to do is come up with my thirty. We got us a captain ready to sign on and a mate that speaks English. I already spoke with the agencies in town and a few of the hotels and lodges. The business plan is solid.”

“Sport fishing, Uncle?” Diego looked at the folder he had just closed. It was a loan application from Reel Big Fish for an operational expansion. They were the largest sport fishing outfitter in Central America—right here in little Jiménez—and had not turned a profit since opening their doors twelve years ago. Ice was also solid, at least until it melted.

“You know a day’s offshore rate is one thousand dollars these days. With two boats and conservatively counting only half the year as fishing days, that’s one hundred twenty five million right there, gross, over twice the asking for the whole business.”

“But what of the costs, Uncle? Fuel. Permits. Labor. Insurance. It’s considerable. Maintenance. Boats take lots of maintenance, you know.”

Danilo squinted, hating the formality of places like this where even his own kin presumed to know better than he. He forced his moist upper lip into a semblance of a smile. Beneath his sallow complexion, behind his pointy cheek bones, within the folds of his cerebral cortex lurked a chained and beaten dog unable to flee, left with the sole options of either wagging its tail or showing its teeth.

“I know enough about boats to know they need maintenance, Galán; we got that all worked out.”

“Well, if you need volunteers when you’re ready to start up, I’ll pay for the gas whenever you’re ready to take me fishing.”

“Atta boy. I’ll remember that. But first I gotta come up with that thirty million.”

His uncle’s shortcomings in financial prudence were legerdemain within the Bonamérito fabric of gossip, and Diego assumed that the money from the sale of Mimi’s share of his deceased grandparents’ finca, about which a number of rumors swirled freely in town, was surely long gone.

“Have you had a good look at their books, Uncle? It’s one thing to project gross revenues on your optimistic forecast of 50% working days. I don’t think any outfitter does that well here. But even so, what about their net? What does this business actually pull in?”

“Their books don’t tell the story, Galán. Some folks don’t have much sense for business. What do these people know about doing business here; they’re from Florida.”

“Perhaps, but they ran a sport fishing outfit there. They know the business.”

“Apparently not, or they wouldn’t be tucking their tails to run back to their Fort Lauderdale.”

“What about savings, Uncle? I imagine you have investments tying up part or most of the fifty million you’ve collected on Aunt Mimi’s farm so far, but I bet you still have a nice chunk of that set aside for something like this.”

“What I have left out of that is already leveraged, Galán. I need fresh money for this deal.”

“Hmm. So you’re here to see about a loan.”

“Just my luck that my nephew,” he pointed to the nameplate on the desk, “is the Commercial Loans Officer. That makes my loan application practically a formality, doesn’t it?”

They both chuckled.

“You know, Uncle Danilo, that what is being purchased cannot be counted as collateral, right?”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, if you want to buy that business, for example, you can’t put up the boats as collateral.”

“I can’t?”

“Technically they do form part of your collateral in a way since the bank would receive them in case of default, but to issue a loan the bank requires collateral that amply guarantees the loan itself, well beyond what is being purchased.”

“Mimi and I are ready to put up her finca to secure the money; it’s only thirty million that I need, and that finca got appraised two years ago by that Johnny Morano for two hundred million, so it’s probably worth two fifty or three today.”

“But Uncle. You sold that to that gringa, right . . . Karmel Greene?”

“Oh but that is just an option. The title is still in Mimi’s name. So, technically . . .” “But the option is a legally binding document. That is a done deal, right, Uncle?”

“Well, if Doña Carmela does not pay the final payment in time, the land returns to us completely.”

“But if she does, then title is transferred to her. Completely. Right?”

“Well, even so, we have equity in what remains to be exercised on her option, so I can still use the remaining third that she owes as collateral. And one third of the appraised value is still one hundred and fifty million or so.”

“Wait, wait, wait, I’m confused.”

“And one hundred fifty million is five times what I am asking. Together with the assets of the business itself, that should be an adequate guarantee.”

“You sold the finca for seventy-five million, Uncle, right? And you have collected fifty million to date and have only a single remaining payment of twenty five million to collect, right?”

“Well, fifty million to go, actually. Doña Carmela and I are in negotiations over the final amount of the last payment.”

“I thought the last payment was not due for another eight months or so.” “Six months, actually, it’s due in December.”

“And she has already asked for an extension?”

“Not exactly, I can’t get into the details until the deal is finished.”

“Well . . . I suppose it is not out of the question to use your remaining equity as a partial guarantee on a commercial loan. But if we do that, you will still need to come up with more collateral since twenty-five million does not cover a loan of thirty million, and to do that we’ll naturally have to make the note mature before her balance comes due.”

“It would be hard for me to repay thirty million in six months.” “Plus interest.”

“Pardon?”

“Thirty million plus interest.”

“Yes of course. Plus interest. Hard,” he caught himself. “But not impossible.”

Ninety-eight percent of the people that walked through his door had no business taking out loans of any kind, and the other two percent—like the Reel Big Fish people—did not need the loans but simply found them more convenient than using their own money. Diego’s uncle was the poster child of the first demographic, aspiring to a seat at the table of the second.

“We can try it,” Diego frowned, weaving his fingers together on his desk “. . . but I think we’ll have trouble getting approval on this one. It’s a little shaky.”

“What about if I push the closing back one more year and secure an extra twenty- five million on the balance?”

“Would it not be better to option the sport fishing business and use your cash payout in December to close? Then you would have only five million to produce on your own.”

“But it’s a steal, Diego. They won’t give me a six month option when somebody will come along any day to scoop it for cash.”

“The bank might agree if you had twenty four months to repay, fifty million contractually guaranteed and if you put up your two hectares as well, something like that.”

“You mean our home?”

“Well, not the house itself so much as the land, which is where the value is. That’s worth thirty million by itself.”

“Oh, more than that,” his uncle frowned.

“I’m sure it is, excuse me. I’m not trying to sell it short, don’t get me wrong.”

“But that’s our home, Galán. If anything were to go wrong we would be in the streets.”

“You could also guarantee just a portion of the loan if you can find someone with solid credit that will guarantee the rest . . . your new partner, maybe?”

“If I were asking for favors, I wouldn’t be here in the first place, nephew. . . “

They sat still on either side of the desk as the cool air blew down upon them and looked at one another for several seconds.

“Sometimes,” Diego said calmly, “it makes more sense to pass on a deal if you don’t have the cash to make it work.”

The realization that his nephew was not going to roll over for him settled in around Danilo Araya like fog on a runway, and a curtain closed around him. His nephew had presumed to lecture him on affairs of business. Diego Bonamérito, pride of the family, mister helpful and considerate, had in effect just told him to go pound sand. Danilo should have resisted the temptation to come here in the first place, though it was too obvious a solution to let pass untested. He imagined Diego going off and having a good laugh at his expense, and he hated those gentle eyes, that phony smile, the ease with which the arms hung and the fingers weaved together. His own family—in-law family anyway, not flesh and blood— was sitting over there all sanctimonious and laughing at him, vengeful, enjoying the power, savoring the rebuke. Little punk.

“Well, I will take my proposal elsewhere, I suppose. I wanted to give you the first chance. I know that it would look good for you here at the bank to be behind this. But I guess I’ll just have to go and meet with Don Miguel.”

Diego managed a pinched smile and a reflexive wince.

“You know best, Uncle,” he said slowly. “But I’d step careful around Miguel Arce if I were you.”

“Oh, one more thing.” “Yes, Uncle?”

“If you hear of anybody looking for wood I have cristobal, nazareno, cortesa for eighteen hundred a pulgada and manglillo and níspero chicle for fifteen hundred. As much as anybody wants, cash and carry.”

“I will keep that in mind, Uncle.”

It was Monday, and Danilo Araya had eleven full days to come up with three and a half million.

Puerto Jiménez Monday 12:00 p.m

It had been years since Johnny Morano had last heard the phrase “two-bit punk” tossed in his direction. Since those days his frame had thickened in his mid- thirties and there were flecks of grey in his thick black hair. He had more or less made good in paradise and mostly put behind his stretch of troubled years behind him. He sat in the Carolina restaurant before a fish fillet casado and a cold Pilsen and watched the downtown foot traffic. He had pulled in on the bus from San José five years ago with a backpack and twenty-five grand in cash remaining from a deal he’d had to skip town over back in Chicago. Puerto Jiménez in the mid- ought’s had everything he was looking for in a place to lay low. And these few years later, the aggrieved party had probably mostly gotten over it and the statute of limitations was coming up back home. He had been accepted into the community, had him a little business, some regular squeeze, and found the climate did wonders for the asthma that had troubled him as a kid.

As he was squeezing lime on his mahi mahi, Danilo Araya leaned up against the half wall to level his pale shifty eyes and his sniveling little nose and intrude upon Morano’s repast with his annoying voice. “Hey Shades,” he said. “I gotta talk to you, can you see me in your office after lunch?”

Morano took a swig of beer. “Yeah sure, Chapín, give me a half hour.”

Johnny poked a few more bites into his pie hole, but Chapín’s appearance took away his appetite. It wasn’t like Morano was some kind of goddamned saint or something, but Chapín was in trouble with the wrong crowd, a crowd that Morano did a little business with on the side. Everything pointed to a score getting settled, and he was not too hot to get very close, even though Morano had brokered the Greene deal with him, Chapín acting the big shot with his wife’s inheritance. Now he was up to his eyeballs in red ink with a rough crowd. It wouldn’t look too good if word got back that Morano was seen talking to him, but it was, after all, a small goddamned town. It wasn’t like you could just act like people weren’t there or something.

He pushed the half-eaten plate away, dropped a tucán on the table, took another swig, and shuffled back to his office, wondering what the sneaky little bastard could want from him.

“You got anybody needs any wood, Shades?”

“Maybe. Whudduya got?”

“Whatever you want in hard wood. Fifteen to eighteen hundred a pulgada, less for anything over ten thousand inches.

“I can move cristobal for you at fifteen hundred.”

“Cristobal’s eighteen hundred.”

“What’s my cut?”

“Whatever you can add on and get away with.”

Shades rolled his eyes. “I think I can do better on my own, thanks.”

“I’ll go seventeen hundred net for you.”

“Fifteen.”

“Ten percent is the best I can do: C1620 an inch.”

“Dry?”

“Of course it’s not dry. Not for C1620 an inch. What are you, crazy?”

“Permitted?”

“Sort of.”

“Right. Sort of.” Morano smiled. “Let me look into it. I’ll let you know.”

“That’s not why I’m here.”

“Why does that not surprise me?”

“The Cañaza deal is not working for us, Shades.”

“You mean with Karmel Greene? What your wife sold her?”

“We did not sell it. We optioned it.”

“Oh. Right.”

“We have to make some changes; the deal as it stands ain’t gonna work.”

“How so? She’s made her payments.”

“We need more money, Shades.”

“A deal’s a deal, Chapín. You agreed, she agreed. I put the option together. You took her money. Pecas made it legal. You can’t change your mind now. You can’t demand more money.”

“There has to be a way, Shades.”

“The only way you can get more money is if Karmel agrees to give you more. And she ain’t gonna do that.”

“Why don’t you talk to her about it?”

“No thanks. Anything else?”

“I guess that’s not really why I’m here, either.” Danilo looked up from the Panama in his hands.

“Okay, Chapín, so tell me why you’re here.”

“I need you to get a message to our friends.”

“Our friends?”

“Don’t get coy with me, Shades; I know your business.”

“That sounds a bit like a threat, Señor Araya.”

“It’s no threat. It’s just a fact. They moved a deadline up on me to a week from Saturday. I got a deal closing the week after that. I need a few more days to come up with the dough and get right with them.”

Morano shook his head slowly. “No can do, Chapín, old pal.”

“Come on, Shades, those guys play for keeps.”

“I ain’t carrying your water on this, bud.”

“You have made money off my back, Shades. Now I need a hand.”

Morano studied it over and worked out the angles and let a long silence hang between them.

“I might can loan you a couple million,” he said. “But you’d have to sign over your property as a guarantee, well, your wife’s property.”

“I can get a loan from Don Miguel if I want a loan; why would I borrow from you?”

“Arce charges up to eight percent per month . . . I might could do it for four, for for old time’s sake and all.

“Arce gives me five.”

“Well, I’m not so set on points. Maybe we can trade, say you bring me the finca next door to your in-laws’ old place on an exclusive. Maybe set aside a few hundred pulgadas of ron ron or something nice like that for me.”

“The Montes finca?”

“Why not? I hear that’s where you’re getting your wood.”

“It’s not titled.”

“Didn’t stop us with your in-laws’s piece.”

Chapín smiled. “So I guess that means you’re not brokering that deal I keep hearing about?”

“We’re working on it,” Morano lied.

“You let me know about that wood. I’ll talk to Don Sylván about his finca. Maybe we can work something out.”

Johnny sat back after Araya left and mulled his position. He chopped out a couple lines and snorted them and sat back to feel it come on. Danilo Araya had taken a turn. Ever since that land sale, he had slipped off into worse and worse choices. Word was he had blown the deposit on a bad drug deal with a Salvadorean mob that had had to blow town too fast to settle scores. And then he’d blown his balloon payment on some sort of gold thing up at Cerro de Oro. Rumor had it he had since brokered a couple small powder deals with Johnny’s crowd, the Canoas boys and their Medellín backers, probably Chapín’s way of getting his confidence back after his run in with the maras. But now he was on the outs again over this five million in “lost” merchandise, and so long as the Colón cartel and their Calí muscle didn’t win the Canoas turf war by one week from Saturday, and so long as Chapín didn’t come up with that payment, then he was living on borrowed time. Word was he had used the proceeds from the Colombians to settle a gambling debt; he had it bad for the cockpit. That and stake his current wood deal, an illegal Forestry Reserve operation, and it was only a matter of time before MINAET caught up with his ass. The mob ran the joint, and any preventive prison for Chapín over illegal logging would be a death sentence in the joint unless and until he got that five million paid off. Plus interest.

Morano didn’t care one way or the other about the guy, other than his desire to now take a shower. He felt sorry for him deep down, but not too sorry to not get a lock on his old lady’s place for a little two million loan. Chapín might squeak by with the Colombians this time, but it was just a matter of time before destiny caught up with the guy. As an investment Morano couldn’t lose on this one. Truth was Chapín was as like as not to blow the loan at the cockpit and then get wacked the next day. Wouldn’t that be the height of irony? He retraced from a visceral glow the day’s fruits and decided it was time to get out of the office and go pay Karmel a visit.

Puerto Jiménez Monday 1:30 p.m

Esquire Lubricio Parimaldo Natas was editing a corporate charter when the front door opened and Danilo Araya stepped into the reception area and up to Silvia’s desk.

“Have him wait five minutes and send him in,” he replied to her announcement over the intercom.

The one-way glass allowed him to examine Chapín freely from a few feet away without being seen in turn, and he noted the half moon of perspiration beneath the sleeves of his expensive shirt, the moistness of his upper lip, and the sharpness of his cheek bones.

“I need you to bust that option, Pecas,” Danilo declared on the heels of the pleasantries, having declined the offer of coffee.

Lubricio was short and squat. He was broad-shouldered, powerful, and sported a gruff demeanor made the more intimidating by his shaven head. He had a congenital skin condition that left blotches of pink on his face, the source of his unusual sobriquet. He was a small-town lawyer that spent his days with personerias, real estate, tax and social security mediations, corporate constitution, national registry reviews, and comparable bureaucratic crap. He had not accepted a criminal defense case after getting burned on his first. Occasionally he got the nod for a civil lawsuit but with awards practically non- collectible, he took the work reticently for cash and where actionable directed the clients that could pay toward shadowy associates for the mediation of accounts. Mainly he used his law license to further his own business interests, which included a couple seedy bars in La Palma and Cañaza, a run-down apartment building in town, a share in a rice operation, and commercial leases of the downtown building where they sat, which he owned. He dabbled on demand in usury but let Miguel Arce take the town’s loan-sharking lead. Occasionally he got involved in shady things, but he was discriminating in who he would work with on ethically marginal cases and by his personal convention only with people from off the peninsula, at least usually. He was notoriously private, even hermetic, and though rumors swirled, he had a solid reputation, and was either openly or begrudgingly admired, nominally one of the town’s de facto leading elders.

“Is doña Carmela involved in anything illegal? Growing pot, maybe?”

“I doubt it.”

“Are you still living on the land?”

“No, we’re cleared out. She lives in my in-laws’ old place.”

“Has she been late on payments?”

“No.”

“If she was breaking the law, we might be able to do something. And if you were still on the land you could refuse the last payment and not move off, and maybe bluff your way toward a settlement. And of course if she was late on a payment, you could reclaim the land through default.” The attorney turned his palms upwards and shrugged.

“There’s gotta be another way.”

“Any other way would require a creative solution, Chapín.”

“Meaning it will cost money.”

“Meaning it will cost a lot of money and not be a sure thing.”

“If it is going to cost a lot of money I need for it to be a sure thing.”

“There is a certain proportionality between the degree of certainty and the amount of money you put up.”

“How much are we talking?”

“Probably ten million, something like that, maybe fifteen.”

“I don’t have that kind of money sitting around.”

“I have someone might take it for a 50% stake. I’d have to run it by him.”

“Greedy goddamned someone.”

Pecas shrugged. “Aren’t we all?”

“You study on it some and I’ll see what kind of dough I can come up with.”

The men stood and shook hands.

“How much do I owe you Counselor?”

“Oh don’t be silly, Chapín. Your money is no good here.” The lawyer curled his lips upward.

“Oh and Pecas . . . “ Danilo turned, his hand on the door knob.

“Yes?”

“If you know anybody that wants wood, I have anything you want for as little as fifteen hundred for run of the mill, no more than eighteen hundred for top end.”

San Miguel de Cañaza Monday 3:30 p.m

“I don’t need your help, Shades.”

Karmel had not recognized the sound of the motor lumbering up the hill and had sat back, wondering if maybe Barb, who was running late, had trouble with her quad and taken a taxi instead. The Four Runner pulled into view through the clearing, and she tensed up and leaned back on the porch swing. The smell of killed meat hung low over her farm, and all the dogs, it seemed, were locked on its scent.

“Karm, look; it’s a complex deal, and this Santa Cruz outfit has also reached out to me about a package of fincas I have in Carate; it’s not like you’re holding solid cards on this.”

She kept any reaction off her face, resigned to hear him out

“I put you together with this place,” he reminded her. “Negotiated the complicated option, handled everything without a hitch, and landed you a great deal. It would have never happened without me, and now look.” He waved his arm across the sloping forest and the lowlands and gulf beyond. “All yours.”

“You got your commission. Up front. You got paid.”

“Karm, real estate’s my business. You don’t know the ropes like I do, especially with untitled land and these mountain people.”

“What’s there to know, Shades?”

The sound of the quad intruded on the late afternoon as clouds gathered and settled in, the rain still not ready to fall. It gave her a lift, and her visitor looked out toward the sound, its intrusion unsettling him, the clip of his stridency ticking up a notch.

“Look at all we went through with Araya and his old lady to get your option through, and he’s at least literate and drives a car. These folks out here will be on board one day and then from gossip from a neighbor insist on twice as much the next. A single finca is convoluted enough, but a package of several to an offshore non-profit group is a very tricky bit of business.”

“Shades, look. You just want to edge in on the action. I don’t blame you for that, but the deal’s framed, and I put it together, and there’s no room in it for you.”

Barbara Salazar roared up into the yard and cut her engine to step off the quad. When her helmet came off it was Morano she was looking at. She crossed the muddy yard in her white rubber boots and stood before the two of them in her short skirt and halter top, as Shades wound up to his final say.

“Well,” he smiled, draining the coffee and standing to look out over the meadow and the lowlands before turning back to Karmel. “I appreciate you taking the time to see me. Think it over. I bring a lot to the table. Let me know if you have a change of heart. Barbara,” he touched his fingers to his forehead and conjured a smile. “It’s always a pleasure to see you. Sorry we can’t visit a bit; I was just on my way back down the mountain.”

“That guy creeps me out,” she said as the sound of his ride faded back into the forest. She sat on the porch swing beside Karmel.

“He’s a piece of work alright.”

“Tell me it’s true, Karm,” the newcomer looked over at her friend, bursting into laughter at the shifty grin she got in return. “You’ll eat that son of a bitch for dinner,” she laughed. “Reduce him and pour him over bananas and ice cream and slurp him up. And I’ll wash the dishes! ACOSA approval? Really? For sure?”

“It’s just verbal,” Karmel said. “My lawyer says it will take a week or so for the edict to follow the council vote. But he says it’s a lock.”

Barbara Salazar jumped out of the porch swing and leapt into the air and pulled Karmel up and made her dance around the porch before she contained her excitement to sit them both back down and get the full scoop.

“Shades claims he’s in touch with Green Leaf—that they’re feeling him out over a tract he says he has on the Carate side.”

“He’s lying,” Barbara said. “Just trying to weasel his way into a payday.” “

That’s my take,” Karm said. “But you never know around here.”

“Well you can bet that if they haven’t reached out to him, he’ll sure be calling them, pitching them whatever he has up his sleeve to lure them away and muscle you. But it won’t work, Karm. It’s your turn! You’ve worked too hard for this to let that guy—ew—get in your way.”

Puerto Jiménez Monday 4:30 p.

Danilo Araya kept his mind focused on the modest gains of the day and the objectives for tomorrow and did not let it drift into that dangerous territory that could get him in trouble in Bambú if he allowed his mind to wander there. It was hard because despite the fact that he had come away from today with nothing firm, he was sure that something was about to shake loose for him, and he felt like celebrating and was not ready to go home. He often found himself envying men that drank; things were easy for them. It was business, he told himself, and it was called cash flow. You can’t make money without spending money. Okay, so he had taken the Colombians’ dough to pay off his Bambú debt. Now he had the wood profits and whatever else he could come up with to settle with the Colombians. It was just cash-flow, nothing more. Well, and timing. He had to do all this before Saturday week or have to skip town till he did. Still, three and a half mill was such a small amount of money and he was such a good goddamned talker that they would probably just rough him up, put a real scare into him, try to collect before making an example out of him.

He might have made it past the Bambú turnoff had his phone not rung. It was his wood client, and the traffic cop was up ahead along the straight-away, so he pulled to the side rather than risk a ticket, and where he pulled over was by pure coincidence within twenty meters of the Bambú turnoff. They discussed their differences calmly this time, and Araya felt good afterwards. He would head up to San Miguel and crack some heads tomorrow. The river was low enough to get the blocks across. It had been high when he used that as an excuse, but the wood had not been ready then, and now it was still not ready but the river was low, so he had to get his boys moving faster to get this wood out and quit making excuses to get paid before his Colombian note was due. That bastard Shades would not put in a word for him, but would stake him with their house as guarantee. He was banking on Danilo getting capped. He thought about that and laughed. In this world, you wanted the dogs off your back, you had to shake them off yourself, wasn’t nobody else gonna do it.

He turned up the Bambú road and felt his insides knotting up and uncoiling. Some people liked drugs. Some liked sex. Some liked to gorge themselves on food. There were those with foot fetishes and others that compulsively washed their hands. And then there were those fanatics that worshiped God and believed the Bible was true and spent their time wailing and singing and trying to convert honest folks to their cause. There were those that liked to hurt people and those that liked to be hurt. There were all kinds of weirdoes in this world.

His thing was cockfighting, and as he neared the turnoff that led back up to the galerón where the cockpit was, he could feel his limbs loosening and his brain chemistry meshing with the approaching pulse of chance and the elegant beauty of the noble avian gladiators.

He parked his car and counted his money, and it came to fifty three thousand colones. He stayed for three hours and left the pit with four hundred fifty thousand colones and walked swiftly to his Samurai, cutting his eyes around to make sure he was not being followed. Now he had nearly a million on hand and only 2.5 million to go to settle his debt. Of that two and a half, Shades had offered two on loan and could surely be squeezed for the final five bills. Putting the house up did not worry him since two million, three and a half million, ten million, whatever, it was all chump change. In business, you make or break based on your ability to channel dough, and it all came down to cash flow.

He had a missed call from Carmona and pulled over down the road to assimilate.

“What do you mean, ate out?”

“It’s hollow, rotted inside. We’ll be lucky to get two thousand inches.”

“But we’re counting on five.”

“Ain’t gonna happen, Chapín. The first one’s fine. But the second one’s for shit. Figured you would need to know.”

He was going to need another tree. Tepe wouldn’t like that. But you know what. Fuck Tepe. He’d sold him a bad tree. They’d work it out. It was just a permutation to the contract that had to be made, change of circumstances. It was a big day, tomorrow.

In business, after “buy low, sell high,” it all came down to cash flow, nothing more, nothing less. And that was the main secret to any successful business.

All you had to do was keep that cash flowing.

San Miguel de Cañaza Monday 5:00

“Be forewarned,” Barbara glanced down at her pack as the afternoon settled around them, the rains still at bay. “I brought Patrón and limes, and we’re going to celebrate!”

Barbara Salazar was a thirty-two year old surfer chick with the self-effacing sense of self to refer to herself as a bit of a ditz. Physically beautiful and well sculpted by standards both inside and outside her crowd, she had a master’s degree in cultural anthropology from Cal State, a rich and doting daddy, and had never earned a day’s wage in her life. She carried neither guilt nor entitlement and had negotiated the overtures from the lineup with enough class to avoid being trashed behind her back. She paid her way everywhere and volunteered at the turtle hatchery on Piro and beach cleanups both in town and on the Pacific side as well as Matapalo. She allowed herself to be dated by a Tico from town that she liked, about whom she spoke sparingly to her girlfriends when asked. She was a regular at the Friday night raves at Martina’s, but she did not take drugs and was usually in bed by midnight and up by dawn for the first set of the day. Local guys had quit trying to pick her up and she could make short work of fresh imports. She did not eat red meat but did not speak against it. She attended yoga sessions and enjoyed them but stayed well outside its militant fringe. She allowed herself reticently the label of environmentalist, but she had Tico friends that would eat turtle eggs if offered, and she withheld the condemnation expected by her erstwhile coreligionists. Fifteen years younger than Karmel, they had met in the lineup a year and a half ago, and their friendship grew not out of causes but from roots.

“Look,” Karm said. She pointed downhill to a balsa that rose from the middle of a landslide scar now re-colonized in secondary. “See him there, up in the top?”

Her guest leaned forward and peered a long time.

“See him?”

“It’s a monkey . . .”

“It’s not a monkey; not in a balsa tree. . .”

“It’s a sloth!”

“It’s not just any sloth. . . ”

Barbie stood up and leaned forward and scrutinized the distance, her jaw slack.

“It’s a sloth prince,” she speculated. “A prince of sloths.”

Karmel laughed. “Well, it may be a prince of sloths, but if so, it is a prince of two- toed sloths.”

“Oh no,” Barbie turned in horror. “What happened to its other one?”

“Silly. There’s two kinds. Three-toed and two-toed.”

“What?”

“The three-toed sloths are more common. The two-toed are kind of rare.”

“How can there be two kinds of sloths and the only difference is their number of toes?

“That one,” Karmel pointed, “is a two-toed sloth.”

“Do you think they can mate?”

“Please don’t talk to me about mating.”

“I mean, you know, could they reproduce?”

“Perhaps with sterile offspring.”

Barbie thought about this a minute. “If a two-toed baby daddy sloth mated with a three-toed baby mommy sloth, how many toes would the baby baby sloth have?”

They laughed.

“Man,” Barbie looked back down. . . “you sure do have good eyes, Karm. For real. How’d you spot him?”

“He’s been there a few days. I’ve been down to check him out. And yes, he is a male.”

“Yeah. He looks like he wouldn’t take no shit from no one. Like a real alpha sloth.”

“Don’t be impugning the masculinity of my man-sloth, girlfriend.”

“Was that a toucan?” Barb jumped at the sound.

“There she goes down there,” Karm pointed off to the southeast. “See her? Loping through the air?” But she could see that Barb could not. “There,” she moved where her guest sat in the porch swing and put her arm out by Barb’s face and pointed. “She just lit in that nazareno tree, see? There? See the spot of yellow?”

“Yeah! Yeah, I see her now. She’s beautiful . . . only how do you know she’s a she?”

“I just made that part up. I can’t tell. I just want her to be.”

They sat and admired the greying of the afternoon, the clouds impossibly still around them, and Barbara spoke up after a long silence between them to channel the cosmic funk that filled her.

“The future is written over everything natural,” she said. “Only it’s written in invisible ink. Like if the sun’s light was ultraviolet we could make out all these messages that God is trying to tell us through the forest but that we are blind to because we don’t see in the wavelengths of light in which truth is written.”

“I think they have places for people like you,” Karmel said.

“Someday, Karm, there will blow up a storm, and instead of water, the heavens will rain a developing fluid that will leave prophecies that were always hidden newly revealed on all the jungle’s leaves and on the trunks of trees and on the hides of animals. Perhaps even on the foreheads of our friends and neighbors, and every message revealed will be unique.”

“You mean like Revelations in The Bible, something like that?”

“Not like the Bible. Like the Tao. And that when that happens we will all wander around in awe at what we should have been able to see all along and will no longer be able to live in denial about cutting trees and diverting water and hunting animals, stunned at the truths we could not see before for not wanting or for having limited powers of vision. And when that happens, Karm, my Matapalo days will be over, and I’ll come up here to live with you. If you’ll take me, of course.”

“And leave Galán in town to all the hot little Ticas on his trail?”

Barbara sighed. “He’s not like that. He could pick and choose if he wanted that.”

“You guys getting serious?”

“Serious is not in my DNA,” she said. “But he’s an okay dude.”

Barbara could not shed Samuel’s echo around the clearing as the last words recessed into the past. He was out there on that world ocean tonight, pushed out there by that thing, that incomplete acceptance lurking in all her sisters’ hearts, hers included, that tragic flaw of the sisterhood that lived a bit larger in Karmel, alone now on the finca that was to be theirs, their dream now emptily hers alone and hollowed out a bit, its veneer shorn of an iridescence it had once irradiated, its substance sucked of its eager concentration of energy back out into the cosmos now, dispersed into the void.

“Have some chocolate, Babs,” Karm said, “lest we stray too far into the dark.”

Barbara wiped tears from her eyes and nibbled.

Karm looked down at the pack. “If we’re going to do this, we better get with it.”