Siotu y Tsaimán

With the Cabécar raiding in small war parties to the south and the Huétar army taking heads and hands of whole hamlets to our west, King Cucumundú—before he had earned his honorific “The Great”—faced the greatest challenge yet to his then eight years of rule. Like his father and grandfather before him, the king sparred with the Miskito when they raided beyond the edges of their Great Swamp homeland. And there were occasional skirmishes with the Corobicí as well. But these northern neighbors had no designs on Bribri territory, nor we on theirs, and we warred after sacrificial captives to curry Sibú’s favor. But with the Cabécar and Huétar it was different. Even in Cucumundú’s great-grandfather’s day the three kingdoms had lived peaceably beside one another along ancestral boundaries without tension or dispute, far less open war. But as our nations grew more populous, the soil rebelled against increased demands, the game dwindled, we married more and more inside our own tribes, and now our neighbors came warring not just for sacrificial slaves but for our very land!

Listen, students! Did you hear? That was the call of a Black-faced Solitaire. How timely that the forest should pipe up at this moment to anticipate my story with such timely foreshadowing. But the solitaire dwells on mountain heights, not in our lowlands, so you can be sure that it is Sibú who knows everything and is in all places at once and knows precisely where I am headed with this tale that has donned the bird’s voice to share with us today. All of you students do as well, even the slackers among you. You all know the story of Siotu and Tsaimán: it’s part, after all, of what you are, what we all are. Yet the story, as does life, evolves, and it’s not its substance, it turns out, but its telling that matters most of all. After all, my young brothers and sisters, it has no substance. It’s just a story.

General Xantroq was one of the king’s most trusted advisors. Born in High Sixaola near uphill Cabécar territory with cordial cross-border ties, Xantroq’s advocacy for common cause with the Cabécar against the Huétar juggernaut was unremarkable. However, Cucumundú’s Cabécar history was forged from lance and bow during his father’s reign, and the king was wary of any prospective alliance. Still, King Cucumundú, wise in spite of his thirty-three years of age, pushed aside his own bias to reach the decision best for the whole of the Bribri Nation. Xantroq’s argument was that the Huétar was an assimilative empire on the move. They had swept up and down the coastline of the Sunset Sea and ruled as far north as Fire Mountain and now coveted from its easternmost outpost of Guayabo fertile Bribri lands. The Huétar, Xantroq insisted, were an existential threat to the very Bribri, not to mention our lands. The Cabécar, he argued, were more like us, that while we might argue and fight as brothers often do, we remained kith and kin, bound by a heritage that neither share with the foreign Huétar. Lord Janxil countered that modest tribute was a small price to pay the Huétar to ensure protection of the more diffuse boundaries with the Cabécar and that despite nostalgic linkages with our highland cousins, that the powerful Huétar could not be long denied their ambitions and that statecraft and not war councils would best mediate our pressing differences.

“Look at how their language has spread across the land,” Xantroq declaimed to the closed council as a gentle rain fell outside the royal pavilion. “It has become the language of trade, the Huétar babel now spoken from sea to sea, as far north as the great Nicaróaga Plain and if envoys are to be believed as far south as the realms of the Boruca and Ngöbe. My King,” Xantroq turned persuasive eyes onto Cucumundú; “only at our great peril can we allow this cultural invasion to infect we Bribri!”

“Honorably spoken, General,” clapped Lord Janxil slowly, “particularly since you are the first line of defense against the Huétar axe. I fear that your Cabécar vanguard will fade into the trees at the moment of judgment and settle for territorial crumbs from the Huétar’s sacking of our lands. I fear your forces will be crushed, General, and you, my lifelong friend and colleague, flayed in our own commons.”

“This Tsaimán,” King Cucumundú turned to Xantroq, “Are you sure he is who he says he is?”

“He’s the third son and is his mother’s favorite and is widely loved among his people. Certainly, he has the ear of King Trandij.”

“Uncle,” King Cucumundú turned to Janxil, “I want you to lead the delegation to the Huétar in Guayabo for a little statecraft and pageantry.”

“Xan, I want you to feel out this Tsaimán, bring him into the fold. Co-opt him, obfuscate, whatever. Buy us some time.

“Guayabo is the tiger’s maw,” Xantroq grimaced and took up Janxil’s side. “How’s about Xarchí instead?”

“Sire,” Janxil was quick to point out, “it gives us the high ground behind, and with the river in front, it gives the Huétar a semblance of cover.”

“It’s neutral territory,” Xantroq reminded, “boundary between our nations.”

“It’s a perfect meet spot,” Lord Janxil purred.

“Yes,” the king muttered, walking around, his chin burrowed in his fist, “Xarchí it is.”

“There,” he turned to his uncle, “you shall contract marriage between Siotu and one of the princes, preferably Tarkhan.”

“Tarkhan, nephew? Why he’s not fit to clean the princess’s chamber pot, much less become your son-in-law.”

“But he is the first in the line of succession, Uncle.”

Xantroq hooked his thumb in Lord Janxil’s direction. “Such a romantic, my Liege.”

While your runners are skinning this out, Xan, and your delegation Guayabo bound, Uncle, I shall decamp the women and children to Léngja Town and complete our defenses of Dawn Town; call in reserves from Xanté and Léngja, full war footing.”

“A well-planned abundance of caution, nephew. But neither of these adversaries would dare pretend against our capital.”

“I disagree with your dismissal of Huétar pretension, Lord,” scowled the general. “But my Liege, removing the women and children sends a signal of weakness in Dawn Town and we must assume that our enemies have eyes amongst us.”

“Will that be all?” King Cucumundú looked around at each of the men gathered, Queen Siábata seated at his side.

“Get to it then.”

Master Ko, you are tempted to object. How can this be true if the Huétar are such fast friends today? Yet, however readily you extoll our friendship with the Huétar, you nevertheless would bristle at the idea of a Cabécar bedding your sister. I know you would; please one of you deny it! We have no truck with the Miskito, you observe, and it’s true, at least inside your living memory, if not my own. Master Ko, you argue inside yourself, we call you the Wise, and yes, you are aged well beyond our tender years and brimming with sage wisdom and sing to us songs of old that instruct and expand our culture and ground our identity . . . but we worry that you lose yourself from today’s reality inside mists from a distant past. While it is very poetic, Master Ko, to claim that Sibú created the solitaire to honor these mythical forbears, it strains credulity, your Worship. You of all people, Sir, know that it does. We reflexively think the solitaire has always made its seasonal home among our mountain heights and that the bird empresses poorly into the metaphorical mythos in which you seek to frame it!

To those that reasonably and properly mutter beneath your breath such objections, I remind you that this moment in time as we sit around this fire is but a single leaf on the entirety of a great Ceibo that is Sibú. It is gratifying to the novitiate to successfully imagine the imaginable. But it is the unimaginable that is our and all nations’ and indeed every person’s biggest challenge and the thing above all others that we must not only see clearly but also embrace and revere. Sibú knows this, shouts it in everything He does. It is today’s chosen song’s most important lesson.

***

Vengol was Prince Tsaimán’s right-hand man. A hardened Cabécar warrior, he was fifteen years older than the prince and lowly born, but a man self-made not only through steely resolve in battle but also through possession of a considerable intellect with an innate sense for strategy and a quiver full of tactics. He leaned into the prince from their perch on the lip of a waterfall.

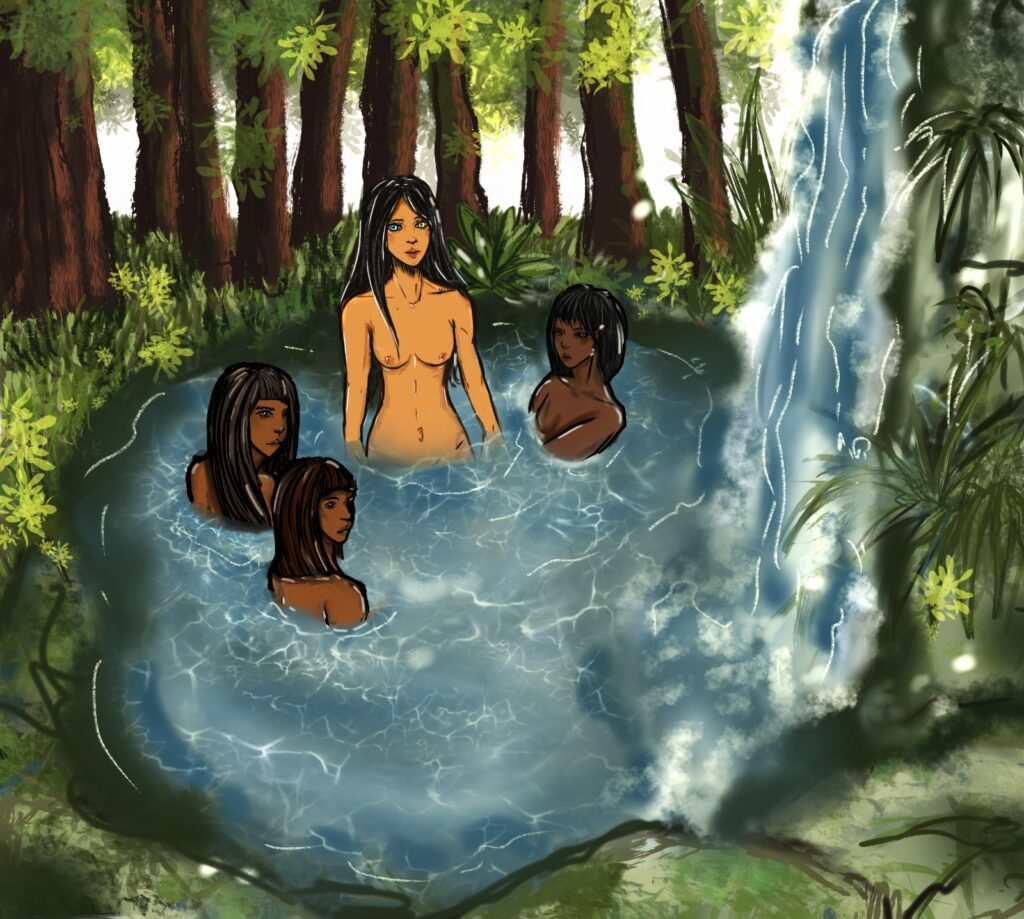

“That’s her on the right, with the small tits, see her?”

“She’s lovely,” replied Prince Tsaimán.

Vengol rolled his eyes. “They are all lovely, Boss.”

“She appears to have different colored eyes,” Tsaimán shaded his own to stare.

Tsaimán and Vengol looked down upon a clutch of four of our maidens bathing in a crystalline pool at the base of the waterfall.

“Their muscle,” Vengol pointed downstream from between the rooting vines of the fig tree they stood behind, his bow now in hand. “Give me the order, Chief.”

“I can’t do it, Old Friend.”

“These are maidens, Boss. Four of them. Maidens, and one is the very daughter of King Cucumundú. There is no better booty than this; and the princess is a Gatica to boot. We can make off with them right now!”

“That one looks Cabécar,” Tsaimán pointed out.

“Three slaves for us and one less for The Uncle,” Vengol reasoned.

“No, Ven. We’re going to do this different this time.”

Vengol turned to roll his eyes at his Liege.

“Have I ever led you astray, Vengol? You gotta trust me on this one. I know what I’m doing.”

***

“Let’s go back and help with dinner.”

“Siotu, Princess, please,” her cousin Chaeta, granddaughter of Lord Janxil, reminded her, “You forget yourself. Indulge your station for once; just relax, will you?”

“Water therapy and beauty go tongue-in-mouth,” intruded Jacosta, an incorrigible arriviste uncomfortable in her own skin. “Here, I can sit on a rock and enjoy the shower, while right here, there is no footing at all!” She sank beneath the surface of the pool and rose to sling water from her hair.

“Well,” Páctlare, the slave girl chirped in, “it’s not like it’s thermal or anything. In fact, this pool is downright cold; why, back home…”

“It’s always “back on Chirripó, up in High Cedar,” Chaeta turned on the Cabécar. “You ougtta start liking local places, might go better for you long term, if you know what I mean.”

“I think I wanna go help out in the kitchen,” Princess Siotu said again.

“Yes, Princess,” Jacosta lamented helpfully. “The times are hard and call for more from all hands, but your calling comes from a different realm than that of tedious kitchen toil and you must recognize and embrace this. It’s a fact and whether you like it or not, you must assume your proper mantle.”

“Well,” Siotu glanced down at the gooseflesh on her breasts. “I’m all cooled off.” She stood. “Let’s head back.”

“What’s the rush?” called down Tsaimán from the lip of the waterfall.

Her coterie huddled neck deep in the water, but Siotu stood to turn to the stranger fully erect, the water surface lapping at her inner thighs to tickle her sex. His accent gave him away as Cabécar, but he did after all speak her language and was being friendly and stood magnificently above her girl squad, so even if he was a raider, at least he was a polite one. He was festooned with a headdress of quetzal and macaw and a breastplate of the ribs of some beast he had surely slain in the forest. He was handsome and muscled and had bow and quiver shouldered and a stone dagger sheathed at his waist. He wore gold bands above sculpted biceps. His loin wrap had spots that recalled the ocelot whose flesh it once shielded from the rain, and he stood with one foot seated in his opposite knee to lean stilly against a spear that rose two heads above his own.

“And who, pray tell,” Siotu shouted over the water’s rush, “are you?”

The Cabécar looked at her, delighted with himself, and chuckled, taking his time to answer. He disengaged his foot to stand normally and conjured a great smile before shouting out loud enough for the guards to hear.

“I am Tsaimán of High Chirripó, son of King Trandij, and I shall be your husband soon.”

“You’re a cheeky fellow,” Princess Siotu called up. “You’ll have to run that one by my father first; perhaps you have heard of him.”

“Indeed,” Tsaimán declared. “I shall seek an audience.”

“You do that,” she said. “I hear he’s trying to pawn me off on Prince Tarkhan. I am to be turned, it appears, into a valley girl.”

“The peacock? The hell you say.”

“A girl doesn’t always get to choose her future,” winced Siotu.

The Cabécar broke into a lungful laugh at the very suggestion of a rival. “I shall pick my teeth with his sharpened bones and nurture the choicest orchid in the forest in my own garden, resplendent before Sibú, for you to steep your tendrils in the fertility of my volcanic soil. The Central Valley is no sort of place for the likes of a divinity like you, Princess Siotu!”

Arrows filled the space that his body had just occupied, and the security detail rushed the maidens out of the pool and into their skirts and trotted them back to camp, the grunt at point, the officer in the rear, and other than a spooked iguana that tore up the underbrush in a mad dash away from the fast-moving contingent, met with nothing untoward.

***

“Tell father I must marry the Cabécar,” Siotu stood her ground. “I love him and will spend my life with him. Please explain this to father? I know he wants me to be happy.”

“You shall marry the Huétar, my love. Prince Tarkhan,” Queen Siábata said gently. “Now say his name.”

“He has a reputation for cruelty, mother.”

“You shall tame him, Sió; it is your calling. Our people need this from you. Now say his name.”

“Prince Tarkhan,” muttered Siotu into a gathering dusk.

***

“So,” Tsaimán said. “My marriage suit has been rejected.” He looked up at the Bribri runner standing at attention.

“King Cucumundú has contracted a marriage with Prince Tarkhan,” Vengol repeated. “Xantroq’s emissary may have been negotiating in bad faith.” He glanced downward. “I may have been taken in.”

Tsaimán returned the half-eaten strip of jerky to his kit and stared above the tree line to assimilate the news. “Hm.”

Xantroq grimaced. “I say we repay them with death from a thousand cuts and extend our raids into the Huétar hearth as well for good measure.”

“Xan,” Tsaimán looked over.

“Yes, Chief?”

“This is only partly political,” Tsaimán admitted after an exaggerated hesitation.

“Let’s just stick to the political part, Boss. Do me the favor.”

“But there is something else here, Vengol.”

“An alliance by marriage between our neighboring enemies opens the door to full-on war, my Liege, on two fronts, and if the Telire choose to take advantage of our distraction, on arguably three. Whatever part of this that is not political can be of little relevance!”

“Perhaps,” allowed Tsaimán, “but there is something I have to tell you, something you probably already know.”

“No Chief,” Vengol protested. “Some things are best left unsaid.”

“This is important, Xan.”

“Please, Lord Tsai,” the warrior entreated. “Sleep on it first and tell me in the dawn if you still must. I fear it is something that I must not hear! No, I am CERTAIN it is something I must not hear.”

“I’m in love with her, Old Friend.”

“No, no, no! A thousand times no! Have you lost your wits, Chief?”

“Some of them,” Tsaimán allowed. “Perhaps.”

“You should not have told me this,” Vengol declaimed.

“You would have me lie to you instead, lie to myself? Deny reality? That’s not my style, Xan; you know that.”

An awkward silence stood between them before Vengol dug deep to get to the truth of it, process that truth, and reach back with the obvious course of action.

“Then we must kidnap her,” he said at last.

“The slave girl,” Tsaimán said. “She’s Cabécar; do you know her name or the circumstances of her capture? Get a message through her to the Princess. Can you do it? Siotu will elope with me, I know it. Set a meet. When’s this wedding supposed to happen anyway? What can we learn in advance? Can we harass the Peacock’s contingent on their advance out of the valley? How shall I kill him? We must make a plan!”

“Lord Tsaimán,” Vengol turned to his friend and master. “This is a bad idea. I will follow you and lead our men to my death if I must and repeat here and now my sworn allegiance to you and to you alone. But I’d prefer to avoid that death if possible. Chief,” he paused, unsure of his choice of words, to look up finally and tenderly into Tsaiman’s eyes. “This is an unforced error; it is entirely avoidable.”

“Duly noted, Old Friend. Now, chop, chop; there is haste to make.”

“I’m on it, Chief.

“There’s just one more thing, Xan.”

“Yes, Chief, what would that be?”

“Is it too late to kill the runner?”

***

My shaman colleagues often disparage Princess Siotu as a traitor to our people, and for reasons of cultural integrity we are right to remember her with disdain, yet the haunting beauty of the solitaire birdsong is testimony to Sibú’s love for Siotu, motive enough to warrant our collective sympathy. Too often as young people, we Bribri, and really, all people everywhere, tend to rush about our lives unaware of cosmic forces at play in the everyday world. And under the influence of youth, rash decisions may be made that are not born from malice as much as from inexperience and yearning. Such is the cautionary tale of Siotu and Tsaimán. My own mentor could not even bear to mention Siotu’s lover’s name, so bilious was his hatred for the Cabécar. But in my advancing years, I have taken a softer view and accord the tragedy of the young Cabécar lord to the same pantheon of divinity that I do our own Siotu. Tsaimán, in his grave miscalculation, aspired at that moment to the very highest ideals in human nature, and the enormous risk that he knew this entailed was only further testament to the magnificence of his ambition if not his reach. You young people cannot help but color your reality with a cloak of presumed immortality, and this is a gift and flaw, both at the same time.

***

Prince Tarkhan dismissed his posse to repair to his river-cane cage, where the rat cowered in its corner for the third straight day. Racacá, the prized rattlesnake presented to him from the highlands above Tabarcia where its kind is commonly found among the jutting and loose boulders of the cold highlands, lay sleepily coiled at the other end of the enclosure, ambivalent about the feast her master had offered up for her delectation. Tarkhan figured Racacá was surely drunk on the thick valley air and like the prince himself after a hard afternoon of pounding chicha and chewing tobacco, disdainful of solid food. He dropped in a few grains of corn onto the rat’s back, and they bounced off its hide to the floor of the cage, the quivering animal making no move to avoid the rain of food. Far be it for the powerful Tarkhan to deny such a helpless creature such a simply conceded comfort as a few grains of food as it pondered its grim little fate.

By all accounts, the Bribri princess to whom he was betrothed, Xhiota or Chotu, or something like that, was beautiful and had the hips to birth a dozen sons and a pliant if not overly endowed bust. It was already prophesied by his more scheming sycophants that their children would vie for a spot on Sibú’s own council of godlings, at least if there were such a thing. Of course, they were all pee-drinking butt-sniffers and their opinions superfluous—even the less toady ones—but it was still good to hear the realm roar its approval through voices close to him. Prince Tarkhan placed no stock in any of the gods but realized the importance of pageantry and ceremony to stoke the loyalty of his subjects-in-waiting.

His territorial ambitions included the Great Valley to the south and the mythical wealth of the Borucan gold fields beyond. But to get there you had to first bleed the Cabécar dry and bind its people to the slave pole. Good old dad had pushed the kingdom’s northern boundaries as far as Fire Mountain in the years before Tarkhan’s birth, and the subjugation of the shores of the Sunset Sea was completed as the prince cut his teeth on the leathery nipples of his crafty mother, its clans quick today with tribute, their priests worshiping a new Huétar pantheon with satisfactory piety and ardor. With sons birthed by his Bribri bride-to-be, Tarkhan would lay the groundwork for centuries of Huétar dominance—a thousand-year rule—and that alone, along with their tributary obligations, was an upside big enough to swear peace with the Bribri in exchange for his bride and not fritter the strength required to subjugate them by force.

The prince had bedded tens of maidens as well as consorts of many of his subjects, and the odd widow or two and was but twenty-four years of age, his best years still ahead of him. Inside himself, though, he had come to find these sexual encounters less and less gratifying. It was fine early on when his conquests were a physicality to overcome, a fire in his loins to quench with a maiden’s blood. But in the prince’s dawning sophistication arose a troubling recognition that such conquests were not really conquests at all but mere bodily functions coupled with the exercise of state power. He confided in no one a growing realization that consent formed the foundation of things really real, that there existed a realm of both sex and power that despite his near omniscient wisdom in all other things, he knew very little about, one that revolved around the contrarian, obtuse, and troubling concept of consent. It was unhappily a law of nature to which he was not by his station natively immune. Despite all the power that was his to wield, despite the priestly caste’s ridiculous assurances of his own immortality, this remained a pedestrian reality, something he could not change but must accept and adapt to its constraints. There was a larger world, not completely unlike the make-believe world of gods and spirits, in which the values of all people, irrespective of tribe or clan, brashly intruded, a world of natural laws that were unassailable by even the omnipotent mechanisms of state. Whatever it was and however it could be best explained, Prince Tarkhan had come to realize that his ultimate happiness lay in the improbable prospect of finding at least one woman somewhere that would love him unforced, a woman that would be his main wife, a mate of his soul complicit in his unbridled ambition.

Now, with his father’s resourcefulness in brokering his marriage to the Bribri princess, this entire troubling philosophical battle was suddenly resolved in an unexpected victory of the highest and most fortuitous order. Now that his wedding night was within sight, Tarkhan could tick the lingering box of true love off his bucket list. It was the second to last checkmark on the path to full maturity, not something the prince took lightly, and he would make short work of seeding her womb with his progeny.

Disappointed with Racacá’s passivity, Prince Tarkhan refilled his cup with chicha and had his boy prepare the pipe. King Tarkhnum was 68 years old but still randy with the slave girls, his mind as sharp as an obsidian lance, and he had long led his growing army from the rear, well beyond the threat of a fortuitous enemy arrow. The king was tight-lipped in his reign, suspicious of the ambitions of not just the officer corps but even of his own sons and only extended his paternal affection to a daughter born of his third wife, a charming little girl a few years yet away from her first blood. But the old man, Stone Giant, as he was known among the people, would die soon and in so doing usher in the reign of Tarkhan, eventually to be lauded as “The Magnificent,” or “Incomparable,” or some comparable honorific.

He whistled up grunting Choto and bent down to scratch the little peccary’s head and whisper into its ear. This night would in generations to come be celebrated in song. King Tarkhan would make sure of it.

***

Despite extensive preparations and collaboration between the two nations on logistics, the wedding of the century did not turn out as planned.

Impressed begrudgingly into her birth nation’s service, Páctlare seasoned the marinade with the tincture of Angel’s Trumpet that Vengol’s scout put into her mitts, and the slow-cooked tapir hams that were served to King Cucumundú’s contingent on the eve of the festivities brought troubled dreams to our armed force and rampant madness as dawn drew nigh. Sure enough, the intelligence of Vengol’s spies proved correct, and the vane and secretive Prince Tarkhan erected his personal camp beyond the protective confines of the main Huétar camp and its platoon of fighters led by the seasoned Captain Khasur. Thirty-five warriors blessed by King Trandij had trotted down from the Chirripó highlands in a mere three days, killing all they happened across that might raise an alarm, and were now the point of Vengol’s lance. As the eastern sky above Xarchí greyed, his scouts garroted the three Bribri sentries agonizing on the mountain slope beneath their foreboding hallucinations as well as four Huétar sentries on the west side of the river amongst the trees beyond the floodplain clearing. As Vengol’s force girdled the Bribri encampment and tightened the noose, Tsaimán led five men across the river and into position before bursting in with three, club and lance in hand, to intrude upon the Peacock’s dreams.

Tarkhan sat up stiff as his personal guards were bludgeoned while struggling to their feet. He leapt from his litter and lifted his axe against the raiders but was slowed by the jasper point of Tsaimán’s lance that pierced his belly, impaling him to the floor. “Quick,” Tsaimán hissed in a language Tarkhan did not understand, coppery blood rising into his mouth; “to your stations; I’ll mop up here!”

Unbelieving, Tarkhan felt the blow of the knife beneath his chest and the weight of his adversary on top of his abdomen and watched helplessly as his killer tore a bite from the pulsing heart ripped from his very body to gloat into his own fading eyes. Tsaimán chewed the tough muscle and admired his handiwork as cries and howls from the nearby Huétar platoon announced the battle.

As Khasur’s men hunkered down beneath the volleys of arrows flying in from all sides, and Tarkhan’s eyes dimmed, Tsaimán tossed the stilled organ to the dirt, wiped his hands clean, and tore off after Siotu.

King Cucumundú was huddled with a disoriented Xantroq when the sounds of battle from across the river were echoed by nearby Cabécar howling in their rushing assault. Those stumbling and wild-eyed warriors that lay hands on arms were slain on the spot by arrow, club and spear, and those that stared somnambulant and helpless into the onslaught—or that ran away—were mostly spared. Cousin Chaeta pealed her lips to reveal snarling teeth and seized her bow to fly to battle and slew one of the enemies with an arrow through the throat before being slowed by the arrow piercing her breast. She made it a few steps further onto the field of battle before stopping to drop her bow as another arrow struck her in the eye and she fell to her knees and turned her head to scan the full panorama of the battlefield in order to fall forward dead. Princess Siotu glared at cowering Jacosta and pushed her into hiding beneath a pallet and flew beneath the rear fold of the tent, clutching tightly her small pouch of jewelry and sprinted to the ordained place and into the arms of her beloved Tsaimán.

The bulwark of the Cabécar force, joined now by fleet Páctlare, withdrew noisily for the diversionary retreat upstream, and Tsaimán, his bride, Vengol, and the five hand-picked warriors previously selected by Tsaimán took to the forest beyond the edge of the clearing to sprint unseen in the opposite direction and make a clean getaway downstream in the dugout Vengol had stashed for the occasion.

As the sun kept rising, King Cucumundú clutched his hands behind his back to walk around and survey the carnage, suppressing the wails that he could release later in private. Khasur forded the river with his grim platoon and onto the killing ground to confront the weary king. But the bodies of the men and women littering the ground and the drugged stares of able-bodied survivors and the huddle of terrified women among the tents suggested rather than betrayal the track of an as-yet unrevealed interloper. Khasur had already seen in the arrows littering his own camp the handiwork of the Cabécar, but he was quick to discard easy answers and to never limit himself in the heat of battle with the self-betrayal of fast assumptions.

“Prince Tarkhan?” the king asked.

“Killed,” replied the captain. “Your daughter?”

“Kidnapped,” the King managed, struggling with the guttural diphthong of the Huétar word for it.

“What’s wrong with your men?”

“Poisoned,” the King said, his mind teasing out the Cabécar slave girl as a plausible suspect. A Huétar scout burst onto the clearing, breathing hard and in his excitement, oblivious excitement to protocol.

“They are in flight, headed back to the mountain, up the Xarchí,” he reported to Khasur. “They are at least twenty strong, perhaps more.”

“You will fly to Guayabo and not stop till your lungs burst,” Khasur commanded. “You are to insist on a force of 100 up over the ridge at Twin Cedars to intercept the raiders before they reach the safety of High View. Tell Commander Shoiga that Captain Khasur shall pursue and to send relief here for our fallen and wounded.”

“We’ll catch the snakes in a pincer. Shoiga shall be the mortar and I the pestle. I shall return your daughter to you, Your Excellency,” the Huétar turned to the king to swear, “every hair on her lovely head intact.”

***

The sin of gluttony was paid by the handful of Bribri soldier braves that never fully recovered their sanity. Others, including General Xantroq, returned from the world of visions within a few days of the events, and upon the wedding party’s doleful return to the shocked capital was able with difficulty to resume his mental duties. On the painful march, he staved off the distraction waging inside his head to settle on something he was increasingly sure was indisputable.

Prince Tsaimán had to realize that he could not retreat up the Pacuare one watershed over, far less the Xarchí River itself without facing the wrath of a prepared and angry Huétar posse. It was simply too far, the terrain too rough to gain High View before the Huétar could slip in at Twin Cedars along a good road from Guayabo to prepare the ambush. Tsaimán had to know that. And the fleeing Cabécar could hardly slip south from the neutral Pacuare into the outskirts of Léngja with our king’s kidnapped daughter in tow. The flight up the Pacuare was either a foolish choice by the brash prince or a subterfuge, and General Xantroq sent runners out to the nearest settlements to beat the bushes and squeeze out the truth.

He huddled with his somber King and Queen in closed council at the royal pavilion, the general’s stomach twisted in knots from the prescribed laxative.

“They are bound, I think, toward Guápil and into the mountains,” he reported. “It looks as if the Cabécar flight up the Xarchí may have been a ploy. A party of seven men and a single woman was seen paddling downstream just above the confluence with the Revnantzún River two days after the events.”

“And how could this path further his designs?” the Queen asked.

“He’s headed for Zurquí,” the King replied. “To lay low for a spell.”

“If he knows the terrain,” Xantroq explained to the queen, “there is a river, the Dirty River, that is born on the southern flank of Mount Zurquí. Upon gaining the headwaters—and just doing that will take him at least a month—it puts him a week’s easy march around Irazu and along ridgelines to reach High View and his reward.”

“A reward we shall endeavor to expedite,” the King glowered.

“It will require Huétar assent,” the General said. “We cannot reach him in time without marching through their lands.”

“And what if Tsaimán does not know the terrain and chooses a different path?” Siábata asked. “And what if he is not bound for Zurquí at all?”

“Honey, he has to get home somehow,” her husband explained. “He can’t double back through Bribri land. He’s bounded to the east by the Sunrise Sea, and he just cut out the heart of the First Prince of the Huétar Nation and can hardly stray into their stronghold. His only chance that I can see is along the ridges that bound our nations.”

“No matter which route he takes up the Zurquí,” Xantroq expounded, “he has no alternative but to march straight into our trap.”

The king digested this and the pluck of the resourceful Tsaimán, whom he would have skinned alive, his twitching flesh palliated with salt and lime, his screams and torments echoed with laughter and taunts. The king would asphyxiate the aspiring son-in-law inside the cloak of his own hide tied above his head and allow the vultures to carry him in pieces off to the Zurquí heights where his soul could float for all eternity for all the king cared. The Zurquí was a no-man’s land, a mountain so wild that neither the Bribri nor the Huétar, nor even the Corobicí for that matter had ever set out to tame it. The cold rugged watery wilderness and its supernumerary beasts of prey were legerdemain across the land, an obvious choice, in retrospect, for the cunning Tsaimán’s retreat.

“One way or the other, my Queen,” Xantroq swore, “I will stop him and present him to your Lord Husband, bound and broken, for judgment.”

“And what of Siotu,” the Queen asked after the General’s dismissal. “What is to become of our daughter?”

But the king had no answer and turned to the tiresome obligation of conciliation with the Huétar potentate, vengeance guiding the Stone Giant’s movements in Tabarcia more even than it did The Uncle in Dawn Town. Siotu was after all, at least for the moment, still alive. The manner of Prince Tarkhan’s death was nothing less than a Huétar humiliation, a slap to the face and stain on King Tarkhnum’s honor that no crafted vengeance could possibly ever cleanse. For the sake of the realm, King Cucumundú could not allow his own anger to distract him from the end game of a lasting peace with the Huétar and the alliance required to next war brutally and decisively against the loathsome Cabécar.

***

The place of the final clash is known to this day by the few hermits and cast-outs that dare inhabit the haunted forest of Zurquí as “The Crossroads.” It is a rock gorge, and there are no crossing paths there. There is today a trail of sorts along the river, but there was certainly no trail in the time of Siotu and Tsaimán, just the orange torrent of Dirty River. But crossroads are not restricted to the physical realm, my patient pupils, and Sibú, without completely abandoning His universal duties elsewhere, settled upon Zurquí as a thick mist among its ghostly trees to watch this confrontation play out and to intervene, as needed, to ensure the equilibrium of cosmic forces it is His duty to enforce. Untamed and hostile though the Zurquí may have been at the time, many roads crossed in the forest when the opposing forces at last collided.

The gorge was hemmed on three sides by rock walls with loose boulders and soils and overhanging trees on the rim. Below lay a camp site on a bar of the Dirty River above flood. The setting was within the stunted cloud forest on the very shoulder of Zurquí, a day’s hike yet from the ridgeline, a day beyond the tall forest below. With its shrouding mists and commanding control from above, Xantroq laid his trap and waited four days till Tsaimán at last walked into it. Failure of a lead scout to return to camp tipped Prince Tsaimán to the lay of the general’s plan, if not the specifics, and he gathered his wits at the unwelcome reality of the changed circumstances. There had always been a risk of discovery. It was hard for a party of eight to move about wholly undetected by human eyes, harder when seven were hardened enemies and the eighth a princess. Still, it was baked into his plan that mutual suspicions after the wedding day battle would dull the edge of his foe’s collaborative flint and that in the muddled fog of hostilities, he would make good his measured flight back to the safety of the Chirripó heights, his prize in tow, by way of this improbable and perilous route.

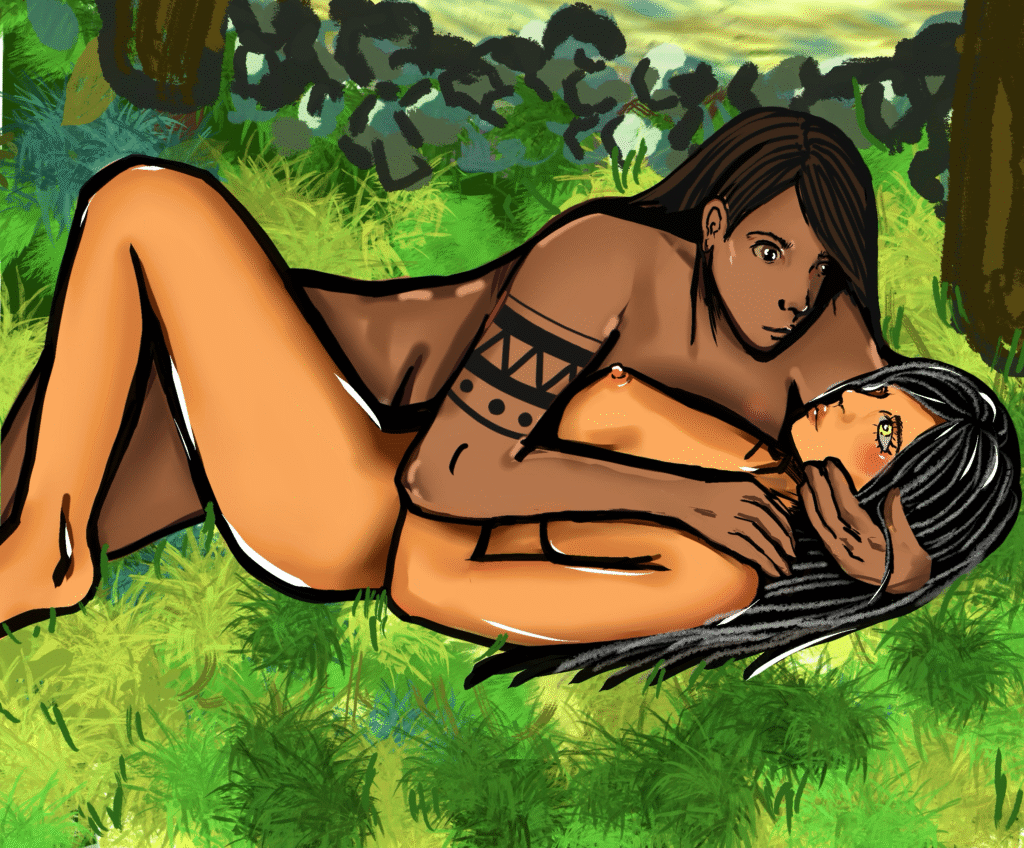

With one presumed casualty, he sent a second man downriver to scout a change of plans. If they might retreat from the trap lain in the path ahead to take refuge among the Miskito in the Great Swamp, he would be surely able to capitalize on their alliance with the sea-faring Caribs from across the salt to bribe his way south along the Sunrise Sea’s coast to Revnantzún delta and thence up the Pacuare, under his father-in-law’s nose, and through the High View front door. With the Huétar surely grown complacent and lazy as the sharp memory of the events was dulled by the indolent passage of weeks, he could surely weave his way by night through their posts and thumb his nose from the safety of their rear. But a Bribri phalanx too strong to evade or defeat was moving upriver two days’ march below his position, and a force of unknown identity and strength dug itself in somewhere above him. Siotu had already missed her monthly blood, but their honeymoon was rejoined daily at dusk and dawn with ritual eagerness, irrespective of the meager amenities to their improvised chambers of love on the dangerous march.

He settled on a fateful camp site in a hidden gorge on a river bank well above flood, and when the rocks came down in a hard rain just before dawn, two men were killed outright and Vengol was knocked unconscious, his left forearm crushed, and was buried in soil and brush. When he awoke and dug himself painfully out into late afternoon, he found his men ceremoniously lain out beneath a flock of feeding vultures, Prince Tsaimán’s headless body atop the heap, Princess Siotu whisked away. Late to the most important battle of his career and helpless from his wound, even the souls of his men and Prince Tsaimán were departed, headed uphill to make their eternal home among the dwarf forest of the Zurquí summit.

It took him hours to build up the fire required for his grim task and in the middle of the night after staring at it a good long while amputated the crushed limb below the elbow and cauterized the stump in a bed of hungry coals to lay up and rest for three nights as the forest reclaimed the vessels of his fallen men and began its work on his amputated limb, which lay on the ground close to where he had cut it off. He drank water from a clean tributary a little way downstream and forced himself to eat and staved off the shock that yearned to set in and pondered all the many mountain tops in Cabécar lands where Tsaimán’s soul could better reside than atop this miserable mountain so far from home, where no one would visit to sing his praises, where he would wander the penumbral forests of eternity alone and cast out, forgotten by friends and enemies alike. Vengol burned his stump regularly from the fire he kept tended. At last, he cut a staff and set off at dawn to climb steep terrain around the gorge that we know today as The Crossroads to push upstream, surely to die, but if not, to gain the pass and limp his way cautiously back to High View and beyond, his warring days over.

***

It was not the rain of boulders that sealed Siotu’s fate but an arrow through her lover’s heart. Just like that, her father’s forces were upon them, and as she rushed to cradle Tsaimán in his final moments, a warrior tore her away and hacked off his head with a crude wooden axe and left her to his decapitated body to rejoin the fight until the last of the Cabécar, but for missing Vengol, lay slain or mortally wounded along the banks and bars of Dirty River. She was dragged wailing off Prince Tsaiman’s corpse by two grim-faced clansmen and was carried and dragged until she finally consented to use her legs, her husband’s blood dried on her arms and hands, eyes swollen, a feral growl displacing language. They watched her make water, sat up beside her through the first night, and two men marched beside her at all times, leaving her no quarter for flight, no opportunity to lay hand on a knife with which to open her throat, no alternative to compliance. Around her raged the talk of what she would be forced to endure to atone for her betrayal, her captors—all familiar to her—unmoved by her station and openly rude to her. Siotu struggled against the despair of her lover’s killing to find some path away from her certain perdition. But with Prince Tarkhan feeding the worm and the soul of her beloved Tsaimán farther away with each downhill step they made her take, there was no way out of this mess, not on this plane. Their son would have one day ruled all lands lighted by dawn’s glow, but now her own people would surely cut him from her belly and feed his tender flesh to beasts in the forest.

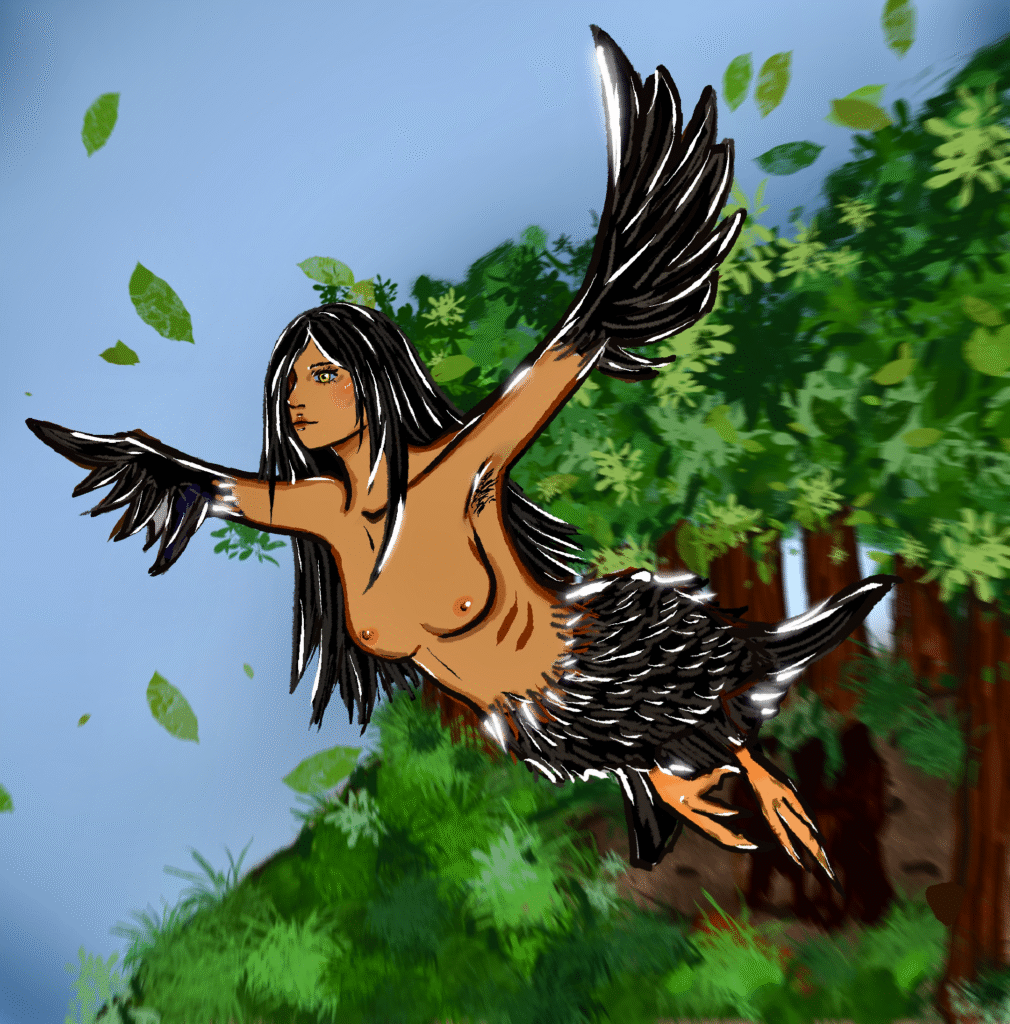

Sibú at last intervened as the Princess attended her needs the second morning. He took the form of white-lipped peccaries to rush her two guards and send them in flight up nearby trees to turn then on the camp itself. The Bribri drew bows and let fly arrows that would not connect with any of the enraged animals, and they too took to trees to escape the rampage. Siotu bolted uphill and ran and ran and ran until she collapsed in exhaustion, her lungs heaving for breath. The spectral menace of teeth clicking and erect shoulder hair turned away into the mists. The chastened Bribri squad gave spirited chase to Siotu. She re-doubled her efforts as she heard their movement below and scrambled out of the forest onto a landslide scar and tore madly up its edges, her fingers digging into dirt and around roots, driving herself upward, higher, ever nearer to where the soul of Tsaimán now awaited her at the top of the mountain.

Half way up she turned to find her pursuers at the base of the slide, moving slowly and taunting her now that she was practically caught. She dug inside herself to scramble up faster as the first two men began clawing the slopes behind her. As she reached for the next root, however, she found her fingers unwieldy and unable to grasp and saw that they had become feathers and felt in the grasp of her feet a solid hold on the world that she released with a giant push into the air and lifted her wings as the clouds parted and the sun streamed onto the clearing. She flew up above the trees and glanced down at the slack-jawed men standing impotent with all their weapons of war and then uphill toward the distant summit still far above her. The forest canopy flew by beneath her as she flapped her wings, her task easier now, her mission within reach.

“Did you see that,” one of the Bribri finally said.

“It looked like she turned into a bird and flew away.”

“That’s what it looked like to me too,” said another.

They had all seen the same thing, and after two days of searching for her in the highlands above, there was nothing left to do but to return hung-dog to Dawn Town with the improbable news.

Cucumundú the Great went on, of course, with the lauded General Xantroq to forge the peace with the Huétar that two hundred years later we continue to enjoy today. The waves of warriors sent into the maw of the Chirripó tiger returned through two decades of hand-to-hand hostilities with enough heads to fill this entire Léngja commons. To this day, though we tolerate the Cabécar intrusion into the Pacuare valley, we tie Cabécar slaves to the altar and till Sibú’s favor with their blood. As we move farther and farther in time from the events of the song, it is easy for the novitiate to mistake in the highlands the bewitching call of the solitaire as Siotu’s funerary wail for her beloved Tsaimán. But you, my pupils, shall never err with this commonplace misinterpretation. For Siotu and Tsaimán dwell together happily—and shall forevermore—in the rugged heights of Zurquí Mountain, and the haunting sorrow of their birdsong is the eternal lament not of loss of love nor life but that of unrelenting and baleful exile. Just as Vengol prophesied in his feverish visions on the side of that selfsame mountain, there are to this day few Bribri and no Cabécar that venture into that wild place for any reason, least of all to mourn the passage of these heroes from bone and muscle into the annals of myth. For though their song is doleful indeed, they glow eternally in one another’s company at the eternal side of Sibú, and on that, my beloved novitiates and brethren, you have little recourse but to take my word.