Un Día EN la Vida de Emiliano Prieto

|

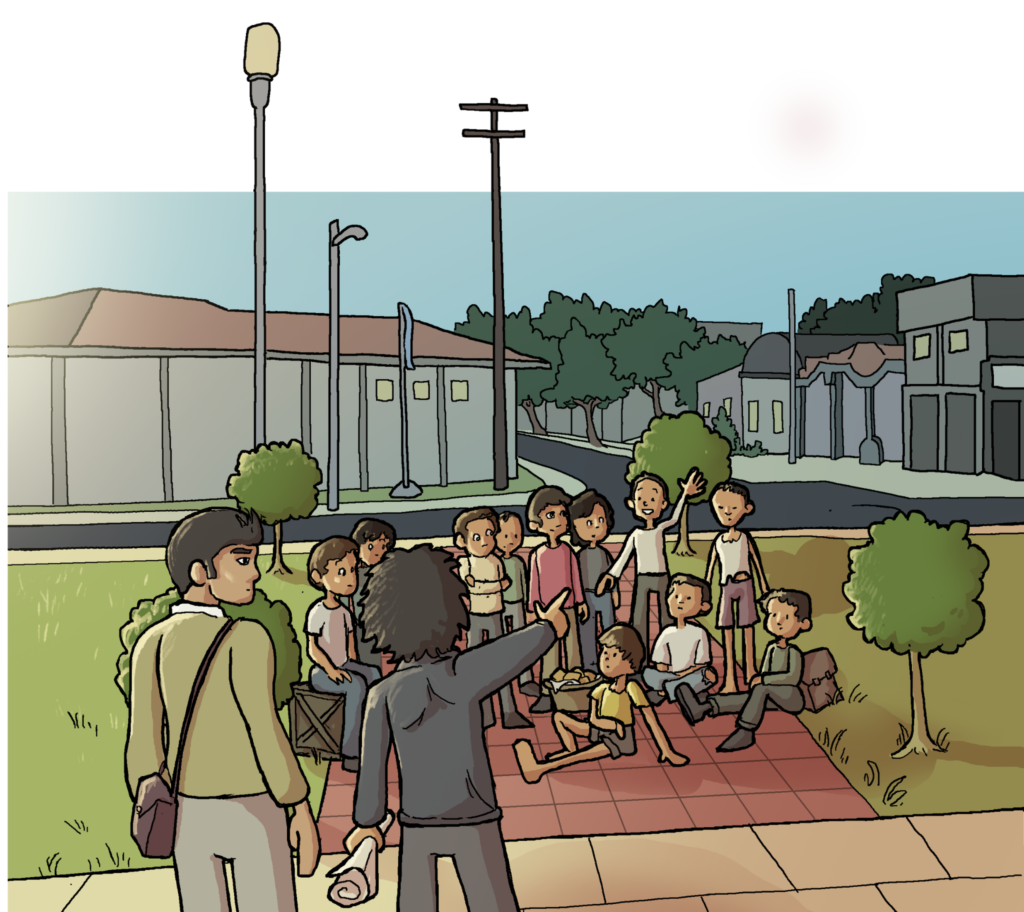

Dawn was an hour away when his eyes opened. The air was cold and he counted the four children by the cadences of their breath. Robertito, Isma, Marta, Deborah…all accounted for in their sleep. The sound of Cassandra suckling and a resumption of Mami’s gentle snore rounded his inventory and he pulled the scratchy blanket over his shoulders and lay in bed and drew the contours of his day, stilling his restlessness so that his family could get what remained of their rightful sleep. The coup d’etat was two days old, uncontested so far, and the streets would be settled back to normal. First order of business would be to see what the paper said about the new generals and chart out the praises he would sing to its advocates and the seditious consolations to its adversaries.

Emiliano Prieto was nineteen years old and the only avenue for books and uniforms and shoes that would allow his brothers and sisters to get ahead in school and keep meat on the table to keep their little bodies strong. Indestructible Mami could manage the corn, potatoes and odd chicken, and mostly cobble the rent and bills from her stand at the market and the meager profits from her coca leaf sales. But with Papi claimed three years now from consumption, the onus of his family was his, and he studied out the tricky day ahead. It had been hard starting out from nothing at sixteen, disadvantaged by immaturity and an ignorance of business. He had lacked the musculature and confidence to claim any place at the contested table. But without room for failure, he had learned the ropes and was a man and it was natural to him now. You had to know your place and that which society claimed as your betters. You had to work it and smile and pretend to embrace things that were humiliations. But with your wits about you there was a bit of cash and small claims to keep the ball in play. Today, however, was hardly business as usual. Carriles had been crowding him for weeks, pushing the boundaries, and today he would settle this business, had to. But he had to do it right; violence was an existential threat to his slumbering family; without him they were sunk and he was dead. Tuberculosis you could not avoid, a knife beneath the ribs an altogether different thing. He called it his pig-sticker, and he carried it. But he had never pulled it. If you did, you had to be ready to use it. It was a law as inescapable as dawn, which now lifted the curtains with a fluttering breeze, its glow rising in the east through a tittering of birdsong.

The girls and Ismael drank api and ate warmed up arepas. Emi bolted his coffee and urged Robertito, who he allowed was now old enough for coffee, to do the same and get ready for school. Mami was bustling already with packs and riding herd, little Cassandra slung across her back and imperious from her perch, weeks away yet from first real words.

“Emi,” Robertito faced him down. “Really, I am too old for school. I want to come and work with you and earn my keep.”

“Nonsense,” Emi denounced before pulling his brother forward to lean and touch foreheads and grip his little neck and soften. “Tito, you have to finish school. You have years to go,” he pulled away and smiled, shaking his head.

“Years. You are to be our lawyer. You will bring us renown and fame. One day you will push all these generals out and lord over them as the president of this nation.”

“I don’t know, Emi,” the boy clasped his brother’s cheeks between the palms of his soft hands to look into his eyes. “How can I do all that? I am just a boy.”

“You will do it! You are the brains of this family. I need you in school. I will need you when you are educated and ready. You must trust me on this. Your turn to lead this family is coming, but it is still a way away. Do as I say. I know what I’m talking about. Anyway, today is Friday,” Emi smiled. “Just a half day tomorrow, so the week is nearly over already, one step closer to your destiny. Look out for your sisters and little Ismael, you hear me? I’m counting on you, little man!”

“Yes Sir!” Tito smiled, and turned to straighten his spine against the new day’s long odds.

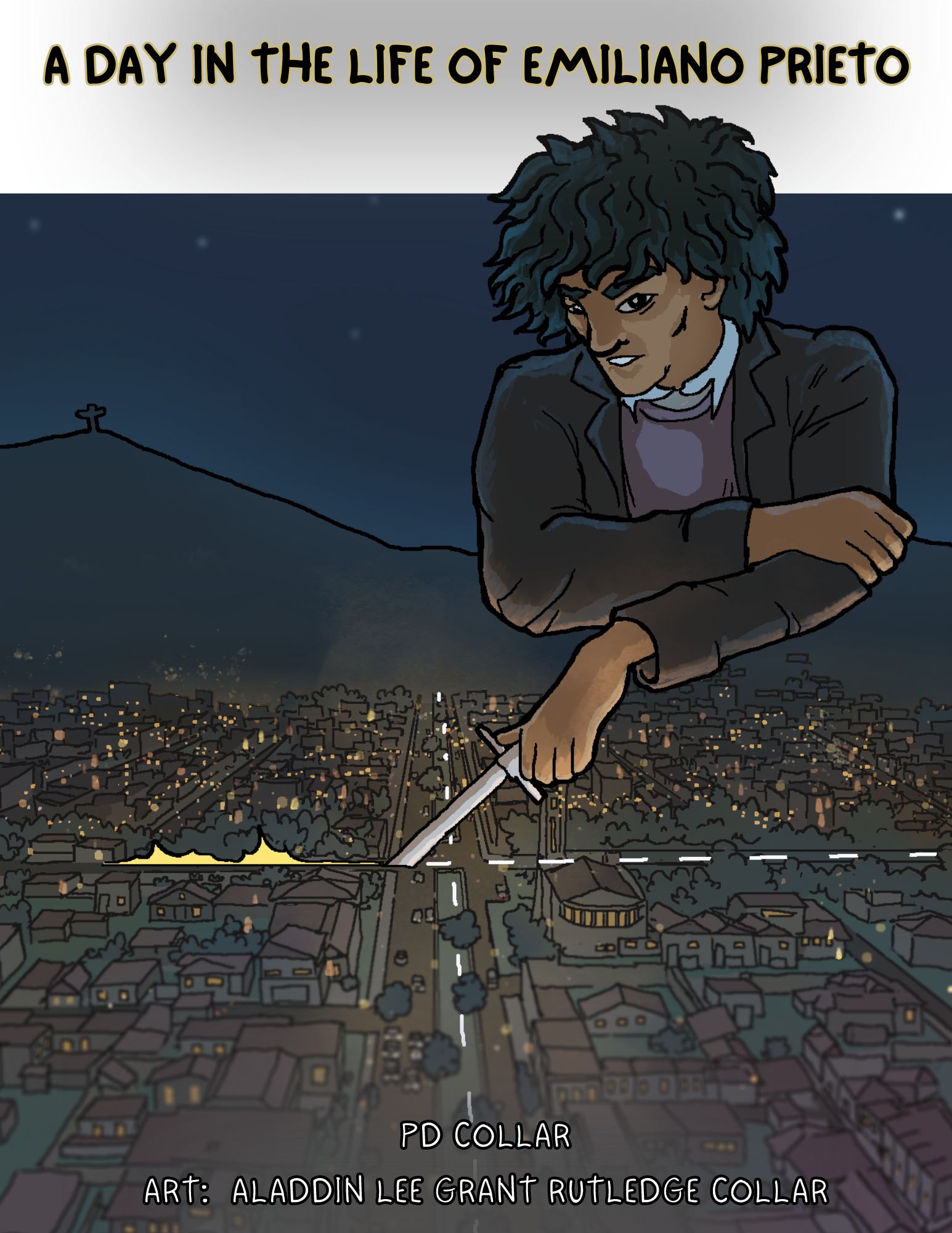

Chapo was waiting on the corner, and Emi shook his partner’s hand and bought a newspaper from the vendor and folded it under his arm as they looked warily around the bus stop and up and down the street of their barrio and smoked from Chapo’s pack. Chapo was light skinned and tall with a thin nose and rangy muscles and understood little Quechua, and they spoke in Spanish but did so softly, away from the prying ears of lurking snoops.

“We have to take out Gato Chino,” Chapo declared. “Without him, Carriles is nothing.”

“Maybe,” Emi acknowledged. “Better to co-opt him.”

Chapo glared back.

“Chapi, your place is solid and you know that. Don’t get weird on me. Where would we all be without your strength”

The bus came and they settled in the back, and in their barrio high on the mountain side, they were un-crowded yet as the bus barreled down the bumpy lane to gather commuters and plod its way toward the quickening bustle of Cochabamba. They talked freely but in measured tones.

“Gato Chino is different,” Chapo hissed. “He has something about him, something savage.”

“He’s ruthless,” Emi agreed. “That’s why Carriles is threatened and has to move on us. But that’s where an opportunity lies. We have to chart it out. Remember, pana, there is always only a single best way.”

“Hey,” Chapo changed the subject. “What about our bigger fish to fry?”

Emiliano blew his smoke out and tossed the butt from the window and was silent a good spell and looked over at last.

“It is very risky.”

“That crowd is a bit tougher than Carriles and his two-bit punks.”

Emiliano looked over and rolled his eyes for form. “For sure. And don’t forget about the law.”

“Yes,” Chapo acknowledged. He French-inhaled and tossed his own butt. “The law.”

“But if you don’t take the bus when it comes along,” Emi mused, “you might get left at the parada with your thumb up your ass.”

Chapo shrugged.

“The times are changing,” Emi said.

“I get touched all the time,” Chapo repeated. “Rich kids. Every single day, viejo.”

“Your complexion,” Emi replied. “They see themselves in you. They confide.”

“It’s an opportunity,” Chapo said, “to seize the day”

“Jerjes has been on my back,” Emi acknowledged. “And I know he has talked to you on the side. He’d like you to break away from me and take up with his outfit.”

“Jerjes can dream; everyone has that right.”

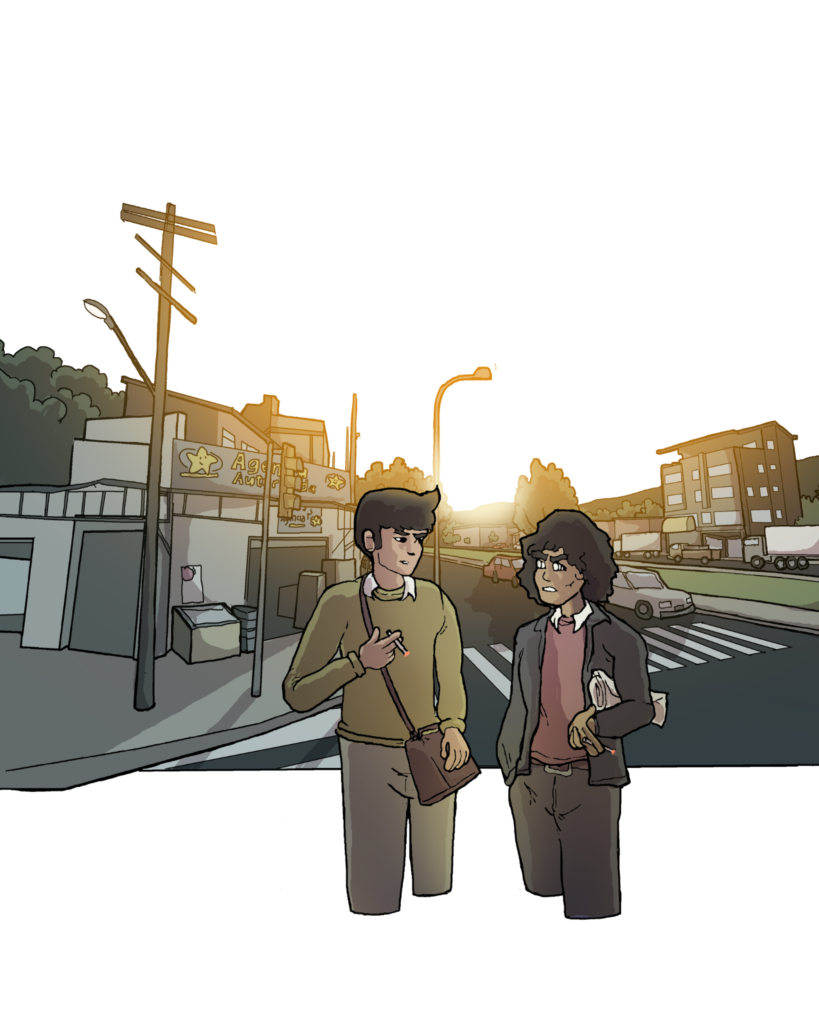

The Praderos converged on the leadership when Emi and Chapo crossed the east-bound lane on foot to loiter in the grassy wide median as the gang sidled up.

Chapo did a head count. “Where’s Jaime,” he asked. The huddled kids swung their gaze down and Javier—the oldest at fifteen—looked right back up, his eyes on fire. “Gone to try his luck with Avenida Dos,” he reported. They were a band of urchins, the boy’s defection an embarrassment to all.

“May it work out well for him,” Emi allowed, “if that is even possible.”

‘Who are you?” he looked at the new kid, head bowed on the periphery, playing with pebbles with the big toe of his bare right foot.

“My name is Adrian,” the kid looked up hopefully, his Spanish solid.

“Are you okay?” Emi asked. “You hungry?”

“No,” the little boy insisted. “I lunched on chuños yesterday; I am fine.”

“Ever shined shoes?”

The little boy shook his head. “But I can learn!”

“Alejandro, scare me up some shoes for this soldier. “You can start learning on your own shoes,” Emi instructed the novitiate.

“Yes sir,” saluted Alejandro.

“How many need to eat and how many can hold till lunch?”

Five heads looked up. The rest shook their heads.

“Jandro, I want you to train Adrian today, take him under your wing, show him what a spit shine is, you got me?”

“Yes sir, come with me Adriancillo,” the boy stepped up. “I’ll show you the ropes.”

“After something to eat first,” Emi said.

“Get with it, troops. You,” he pointed to the hungry ones, including the new boy, “let’s go get something to eat and get ready for the day. Diego,” he turned to the second oldest. “New plan. Today, I am going to point out the cars and you and your crew wash them. Anybody steps out and says anything, you tell them, like this: ‘Courtesy VIP detail by the Praderos, orders of the boss,’ you tell them just like that and don’t pay them any more mind, just scrub all the harder.”

“But…“

“Don’t worry about it; I’ll see you get paid.”

“Yessir!”

The Praderos scattered and Chapo sat down on a concrete bench to case their turf while Emi took the hungry to get food.

“Flaco,” he summoned his problem child. “Walk with me.”

The gang pushed forward and Emi turned to the twelve-year-old.

“I or Chapo or any of us catch you huffing, just once more, you’re out on your ass, you understand?”

The kid shuffled along and looked down, sullen.

“Flaco, goddammit, stop and look up at me.”

Sullenly, the child complied.

“You want to ruin yourself that’s fine by me. You go ruin yourself. But you are not going to run with the Praderos and pull that shit.”

“You’re not my father,” the kid glared at him.

“You damned right I’m not, thank God! I’m your fucking boss!”

“You can’t make me.”

“No,” Emi glared down. “But you can make yourself. It’s your call. You can be a punk. Or you can be a man.”

Flaco looked up after casting his eyes around the boulevard and took in Emi sidelong, his face churning. “Sometimes I just can’t help myself,” he said, turning inward, clouding up before bursting into tears.

“You ass wipe,” Emilio took him under one arm to squeeze him and pull him off the ground. “You’re better than that shit. You’re a person. It’s a thing. You do as I say, or I’ll kick you out. That’s final. It’s your choice: last chance. Now let’s go get something to eat.”

***

In the third month, the salteña hour rolled itself out at ten-thirty, Praderos fanning out across a ten-block radius to deliver the morning treats far and wide from the shops along the Prado that baked them to the leafy neighborhoods bounding the Prado. Mornings were slow until the lunch

crowd started rolling in, and the neighborhood salteña incentive was not banking much. But it was something, and something was better than nothing, and the troops hustled through the streets with makeshift baskets and cloth mantles to hold in the heat, and it was a small bit of cash every day before the real business of tending cars and hustling tips and begging could get underway in earnest. Chapo scoffed at it, but it was a 5% bump in profits and practically an institution now. Plus, everyone got a salteña out of it, a rare treat in the days before the great salteña distribution drive.

Social Friday was their biggest day of the week. Date Saturday was ground he was moving on, territory unconsolidated and still in play. In the bubble-gum hour between eleven and noon, Maimonides pulled Chapo away to a bench in the shaded median to continue the communist world order indoctrination in progress. Jerjes’s driver screeched up in a Corolla as Emi guided a patron back out of a parking space and took his tip to sidle out into the street and get in the back seat as bade.

“Tell me how it works,” Emi said.

Jerjes turned around in the passenger seat and let his shades slide down his nose to reveal his eyes. The driver chuckled.

“Laugh all you want, Gordo, you’re just a driver,” Emi tapped him gently on the side of the head. “What’s the low down,” he turned to Jerjes. “You gotta explain it.”

“Here,” Jerjes handed back a plastic bag with bags inside, doses, Emi figured.

“That’s ten bags, and they weigh a gram each. You owe me one thousand bolivianos, and I’ll collect tomorrow same time.”

Emi looked at the bag of drugs.

“You sell each for two hundred. You make 100% profit. Child’s play.”

Emi had twenty-five hundred in cash in the business section of his wallet. However uncertain their start, he could at least cover the spread.

They had driven five blocks. Ahead, Jaime and Miguel were hot-footing it back empty-handed and wide-eyed. “Okay, Jerjes; come collect tomorrow, then. Let me out now!”

The boys pulled to a halt and jumped around their boss as he stepped from the car. “They beat us up and stole our kit,” Jaime managed, holding back tears. “We fought them but it was no use; there were too many. Look at Miguel! They were just too strong for us, boss!”

Miguel pushed his face up to show off his shiner with calm pride, Jaime a mess of nerves, the responsibility full on him.

“Avenida Dos boys?”

Jaime nodded.

“Let’s go.” Emi ran with them the five blocks separating them from headquarters and across the west lane of the Prado and up to the bench where Maimonides was busy extolling the virtues of Leon Trotsky.

“Maimo,” Emi said. “We need your car, let’s go!”

“Hey,” Maimo objected, “what’s this all about; I’m not part of your business.”

“Maimo,” Chapo turned to coldly insist. “We need your car. Now let’s go!”

They jumped in Maimo’s old man’s Datsun and Emi pointed out the way, looping through back neighborhoods to come out on Avenida Dos and cut off the six Carriles punks lolly-gagging their way back, a couple blocks shy of safe territory. Chapo burst from the car and dragged two of them by the scruff of their necks and a third with kicks in the ass and ribs into the back seat, their three cohorts making good their escape down the avenue to the safety of greater numbers.

“Hey,” Maimonides found his spine. “What is this? I got no part in none of this shit. I’m not no gangster!”

“You,” Chapo glared at him and settled his voice into a cold low tone, “are the driver and over 21, and you are the most responsible of all. So, settle down and do as you’re told.”

“Punks,” Emi said gently, slapping each of the captives crammed between him and Chapo in the small back seat, Miguel and Jaime crowding into the passenger’s seat in front. “Welcome to your new world of shit.” The small one, a kid of twelve or so, glared with black ferocity, un-cowed by the circumstances. The older two, fourteen and fifteen or so, began to whimper.

“Arroyo Seco,” Emi instructed the driver, “keep east past the Melcha; I’ll let you know when we’re there, to dump these bodies.”

“Do it,” Chapo hissed, clicking his pulled stiletto to clean his fingernails and glare at Maimo through the rear-view.

“What do you think you’re doing on our turf,” Emi turned gently to his captives, “ganging up on my crew?”

“I shit in the milk of your mother,” said the little one… the little killer.

Emi grabbed the hair in the back of his head and pounded the kid’s face with his fist hard a single time and pushed his head down to release his grip. The kid leaned forward without a sound and felt his nose with a tentative finger and held his tongue.

“We were made to,” the oldest got chatty. “We had to. We was ordered to, you can’t kill us. We didn’t mean no harm. Boss says we gotta rub at the edges of our turf. We got no choice,” he blubbered. “Please don’t hurt us, we’re just trying to make a go of it.”

Chapo leaned over and pulled the little killer’s head over by the thick head of hair and laid the edge of his blade along where the carotid ran. “We best settle this one down,” he said to Emi, playing out his part of their little routine. “He’s got a terrible attitude. Let me cool his jets, boss. Right here and now.”

We’ll get there,” Emi said.

“Wait a minute; Maimonides pleaded. “You can’t kill nobody in this car. This is my dad’s car. He’ll never let me take it out again!”

Chapo leaned over the driver’s seat. “This is the dictatorship of the proletariat, old pal,” he said gently. “This is what it looks like in real life.”

“Whudduwe gotta do to make this right,” the middle kid blubbered. “You got your shoeshine kit back. We didn’t mean no harm; you can’t kill us; we’re just kids!”

“Pull over, Maimo,” Emi said.

He pulled the little killer by the hair across his lap and turned his head up to look him in the eye, blood running from one nostril, nothing broken, no marks. “What’s your name, punk?”

The kid spat in his face.

Emi smiled, wiping the spittle with a knuckle from his eye socket to fling it on the floorboard.

“Okay, Little Killer; you go do your math,” he smiled. “And you want to come back smartened up and be nice, maybe I can make room for you.” He hauled the kid by the waistband of his pants over his lap and out onto the sidewalk.

“Little Killer…” he smiled at his remaining captives. “He is indeed incorrigible. Maimo, what are you waiting for?”

Chapo laughed and sheathed his blade as Maimo slipped the clutch.

“Look, kids,” Emi turned his head. “We’re not going to kill you over a shoe-shine kit. Not this time. But you gotta think about your future. Maybe Avenida Dos has it going on… Maybe Carriles looks out for you…and maybe not. Tell you what, little guys… you come around to my turf but politely next time. You come see me. Maybe I let you work for me. Maybe. You dig?”

They could not nod their heads vigorously enough.

“Maimo,” he announced. “Let’s let these little men out. Pull over.”

Chapo got out and held the door and the kids got out and backed away to the sidewalk to get their bearings to beat it back to Avenida Dos. Emi directed Maimo back to the Prado, to the street corner that marked the northern boundary of Pradero turf. Jaime and Miguel got out and Chapo moved to the front seat. The two kids looked around them, the shoeshine kit shouldered, chests puffed up, to resume the business of hustling up shoes on the sun-beaten boulevard.

“Sorry about that,” Chapo turned to his political mentor with eyes swimming with simulated sincerity

“You assholes could’ve got me in trouble,” Maimo burst out, safe now in the aftermath.

“Sorry,” Chapo repeated, twisting his face in empathy.

“Maimonides,” Emi pitched in. “It was a great favor, and we owe you.”

“You guys are out of control!”

“Mai,” Emi entreated. “You are older and wiser than we. We’re just trying to make it out here. You have your father’s blessing and money.”

“I thought you guys were going to kill those little shits.”

“We don’t kill children,” Chapo smirked. “What kinda outfit you think Emi runs?”

“Hey, Maimo,” Emi said. “You’re in the U. You’re in the middle of it. What’s up with all this cocaine thing? You ever tried it?”

“Me? Not hardly. But it’s all the rage. A lot of the cool kids are into it.”

“How come you never tried it,” Emi asked. “You’re rich.”

“I don’t run with that crowd,” Maimo said. “Never had it offered to me. Probably wouldn’t turn it down, just never had the chance.”

“Want to try it out,” Emi offered.

Chapo turned his head to study his partner over.

“Well,” Maimo laughed. “What, are you offering? You got some?”

“Tell you what, you do us one more driving favor, and I got a little bag for you, and you go check it out and report to Chapo what you think, and whether you might have some pals in the U might be interested. I might have a bit of work for you. You might even make a little dough…” Emi raised his eyebrows.

“What kind of driving I gotta do? I ain’t going for what we just went through.”

“Nothing like that. Pull over; let me talk to Chapo a sec.”

“They’ll all be huddled,” Emi said, “trying to figure out what todo.” He pressed six of the baggies in Chapo’s palm.

“Where’d you get this,” Chapo asked.

“You pull up with Maimo right in front of their headquarters,” he said low. “Tell them you want to talk peace, but that you’ll only talk with Gato Chino, and for him to get in the car.”

“Muscle to muscle,” Chapo reasoned.

“Yeah,” Emi smiled.

“And you tell him about our push into Date Night and the disco scene. Talk it up; make it sound real, not an ambition. Tell him to turn them for two hundred a pop, going rate, and to not mark them up a centavo more. Tell him that he comes on board with the Praderos, that he keeps the dough as a signing bonus and gets a full one third stake of our Saturday night scene, provided he can prove himself and bring over a few more defectors.”

“I’ll have to be cool about it…“

“I think those bags will distract him. Act like it’s all regular business for us.”

“It might work, boss!”

“Maybe.”

“He’s still bad news, Emi.”

“We’ll keep our eye on him. There’s ways to deal with him once Carriles is out of the way.”

“Right now, Gato’s the lynchpin.”

“Yes,” Emi smiled. “Right now, we need him.”

***

Back now, Emi was pleased at Diego’s initiative in his absence. He had two cars washed, don Alfredo’s Peugeot and Miguelito’s Chevy from the levy. Both were regulars and good tippers, and Emi gave the thumbs up and pointed out don Alissandro’s Fiat and the Lucci brother’s Celica GT to follow up with. He paced the sidewalk in front of the seat of his empire and smiled at the patrons busy with their extended lunches as the sound of dice emerged from early drinkers in the back. It was one o’clock and he recognized the silver Mercedes stopped a block away at the red light. Prieto shuffled over to his beg squad, smug at the prodigal literacy of little Atencio. The sign said “help with our education,” and Atencio read dramatically to his youngest Praderiños, the precious little crippled Ada and her dour and protective kid brother Vladimir. “Perk up, little thespians,” Emi smiled to motion down the street. “The queen of alms is on her way!” The collection of poems that Atencio read aloud was by Pablo Neruda, a gift from the selfsame benefactress on her way to thumb her nose at the men-only Friday rule and drink and play cachos to show that she could do whatever she wished. Emi edged away to go lean against the wall, discreetly down the way from the entrance steps.

She emerged from the passenger seat and made a beeline to interrupt the reading and reveal the cover to confirm the title. She squatted down to coax a smile from little Ada with a caress of her chin. He could not be sure from the brief flash but from the color he thought it was a thousand boliviano note that she dropped into their hat before rubbing the two boys’ heads and leading today’s date on the wrong day toward the steps. Emi turned to greet her with a touch of his forehead, and she bounded over to stand before him and clasp his arm like a man and smile. He let his shades slide down his nose to reveal his eyes, and she stuffed a wad of fifties and hundreds into his shirt pocket.

“Tomorrow,” she instructed him. “The League of Women Voters is meeting at the Jewish Club, the Shai-Bet, you know where it is?”

“Over in Centro Este,” he said.

“You know it. Get your little act over there,” she hooked her thumb back at his beg squad, “and I’ll land you five thousand from my crowd of blue hairs.”

“We’ll be there,” he assured her.

“You do that, Emiliano,” she smiled. “Gotta run lest I get my stallion all unsettled,” she grinned.

“Go then, have fun, turn the tables in there.”

“But you gotta use that money on food and medicine and housing,” she glared. “No booze, no drugs.”

She leaned forward and kissed him on the cheek and broke into a giggle and winked before turning to bounce back to her gallant to take his arm and mount the steps, where the conversation fell as eyes broke uncomfortably upon her brazen entrance.

Where money intruded, the conventions of society fell into a muddled heap. There, all bets were off. He looked over at his beg squad and they looked at him with wide eyes in glances at the hat. He motioned for Atencio to pocket the bill and get it out of sight. He stepped out across the sidewalk and moved Diego’s crew over to the Alm-Queen’s Mercedes. “Priority,” he tossed his head.

Don Emilcio pulled up in his Range Rover, and Emi waved him down the street to the closest parking spot on tap. He guided him into the space, all smiles.

“Hey Emiliano,” the old man emerged from the driver’s seat, his oldest son and heir apparent from the passenger’s side, a younger brother and an unknown elderly pal piling out of the back. “Thank you for your help the other night with Carlitos.” He shook his hand firmly and gave Prieto an unexpected embrace, albeit light, waving his oldest son and heir-apparent over with the package.

“It was only a flat tire, don Emilcio, what would you have me do, allow don Carlos to dirty his hands all dressed up and on his way to the cinema with your beautiful daughter-in-law?”

“Two little kilos of cuis cuis in appreciation,” the patriarch beamed, his son hustling forward to present the packaged meat ceremoniously with a grim smile, clearly dubious about this lesson in patronage and largess from his masterful old man, Emiliano Prieto little more than a beggar in his entitled eyes. Don Emilcio owned the largest dairy in the nation and had other things on the side, including a guinea pig operation.

“Oh no,” Emi demurred, looking down at the packaged meat held out to him. “I could not think of it; it was nothing, simply my duty.”

“Don’t be silly,” the old man scolded. “I insist. Take it home to your family, compliments of the Sibanchas!”

“Well,” Emi relented. “If it is like that, then I cannot refuse. Thank you from the bottom of my heart, don Emilcio!”

Across the boulevard, today’s fifth pair of soldiers came strolling up. They were out in force on today’s first full day of normalcy. Nobody had been killed and the old general had flown off to exile in Paraguay yesterday and now a new general ran things, and their actual names were of little consequence. Emi recognized Pansa, from his own barrio. He had been drafted a couple years ago but stationed in Cochabamba and was nearing the end of his obligation.

The soldiers were across the street from him now, and as the Sibancha party filed up the entrance steps and into the restaurant, Prieto sidled across the street.

“Pansa,” he called out.

“Hey Emilianón,” Pansa turned to smile. “You keeping all these blue-bloods straight and narrow around here?”

Emi scowled. “Hardly. How can you ever control those with no conscience, to whom all is given and nothing expected?”

The second soldier scoffed, and Pansa introduced his as Silvio. Emi shook hands and smiled.

“What are you selling now, Emi,” Pansa pointed at the bag. “Human hearts?”

“Hey,” Emi said, handing over the package. “Take this home to your Momma,” he smiled. “I know it’s tough to take anything home these days with the pittance the Army pays.”

Pansa nodded for Silvio to accept the package.

“Looks like you boys survived the golpe,” Emi smiled.

They all laughed at the inside joke. Only the upper crust shifted positions. The working stiffs always plowed ground and tread water. It was just the way it was.

“What can we do for you,” Pansa glanced at the meat.

“Oh no,” Emi replied. “I just want to show my appreciation for your sacrifice. I know it’s tough.”

“Don’t be shy,” Pansa insisted, not far from completing his four years and openly tilling the ground here and there for what was to follow on the heels of soldiery. “There is no titty for the baby that won’t cry.”

“Well,” Emi faltered, sweeping the sidewalk with an embarrassed glance.

“Speak up,” Silvio insisted.

“That Carriles,” he broke through his façade of reticence. “He beat up some of my boys this morning and stole their pennies.”

“He is a weakling,” Pansa scowled. “A coward.”

“You want we should rough him up,” Silvio asked hopefully. “Bust his teeth out?”

“Oh no, nothing like that.”

“We can go pummel his kidneys,” Pansa offered, “work his knees over a bit…”

“Actually,” Emi said. “Maybe you could help me. Not like that; I mean him no harm. But if you could detain him for a spell, walk him off like he’s wanted downtown, let him sweat a bit and clear him off his turf for a couple hours…well, that could be a good lesson for him and a great help to me.”

“That’s beyond our authority, of course,” Pansa regretted, rubbing his chin to study it over. “It’d be easier to just rough him up since we might get in trouble if we’re seen hauling him around. Still, today, of all days, nobody has a fix on what our authority really is. Let me look it over.”

They shook hands and the soldiers continued north along their way. Emi re-crossed the street back to his station as don Pánfilo, mildly drunk, emerged from the restaurant and appraised his immaculate ride to whistle Emi over and lay a fifty on him. Emiliano pocketed the bill and pondered the bad dominoes all lined up to fall on his old pal, Carriles. It was five o’clock and the restaurant was in transition, emptying of its afternoon crowd in the lull before the evening drinkers would start up in a couple hours. He fretted over Chapo’s continuing absence and paid out his beg squad with today’s huge haul and instructed them on tomorrow’s mission at the Shin Bet and sent them and the car-wash squad off to go and eat from the leftovers begged from tables throughout the afternoon. He left word with his lookouts to send the shoe-shine squads his way when they showed up to clock out, and he moseyed down the street to restore his energies with a bite to eat.

Dusk fell, and he collected from his shoe crew the two thirds that were his and accommodated his third in his place in his wallet and the company’s third in its compartment. Chapo, irreplaceable, was taking too long and was vulnerable alone in the field, and Emi relived punching the kid in the car and shuddered at what was sometimes required. You could delegate as circumstances allowed but never separate yourself from actions or commands. Jerjes pulled up outside and glanced out the back seat window at him. Emi waved his head to call him over. He had gone to him this afternoon. The days of going to were coming to an end and those of having others come to him beginning. Jerjes scowled and had Gordo park and sauntered warily out onto the street and across the sidewalk and into the joint.

Emi passed one-thousand-boliviano banknote, palmed, in his handshake.

“So fast?”

Emiliano shrugged.

“I’ll swing through in another half hour and lay another ten bags on you, twenty if you want.”

“Tomorrow,” Emi said.

Chapo hopped out of the Datsun now pulled up behind Gordo’s idling Volvo and Maimonides sped on, back to his conflicted roots. Jerjes took his cue and shook hands with Chapo on his way out.”

“Taquiña,” Chapo called out to the waiter.

“We celebrating,” Emi asked.

“That’s the size of it,” Chapo said.

The waiter brought the liter bottle and set short glasses in front of them. “Want cachos?”

“No dice,” said Chapo. He waited till the waiter moved away out of hearing. “While I was off with Gato Chino, soldiers came up and hauled Carriles away,” he reported.

“No shit?”

“I didn’t stick around, but there was low clouds over Avenida Dos.”

Chapo poured again, and they clinked rims, and he grinned.

“Gato Chino blink?”

“We got us a partner.”

“Gotta be careful what we ask for,” Emi said. “Might get it.”

Chapo drained his glass, and Emi poured it full again, the night taking on new contours.

“He’s not so bad,” Chapo allowed. “He’s doing the best he can with what he’s got to work with. Nobody has all the answers. I think we can work with him.”

“So, how’s it gonna break, with him and the Avenida boys?”

“The soldiers changed up the odds a bit.”

“So the leaves are changing?”

“Yeah.”

“Think he’ll hold?”

“We’ll have to see.”

Emi drank his glass down. Chapo poured him another.

“How’s Flaco doing.”

“Huffing again.”

“Dumb ass.”

“Can’t win them all, Emi.”

“He’s gone tomorrow.”

They drank the next together and divided the remainder evenly, Emi pouring, and drank them, paid, and walked back up the street where the Prado was all warmed up.

Old man Atencio had left the ignition on and his sons had gone off with pals of theirs hours earlier, and he was drunk and scratching his head. Emi and Chapo pulled a push brigade and rolled the car out and stopped traffic in one of the east-bound lanes to roll start the old man’s ride and get him on his way, and Emi pocketed the tip. “Hey, Emi,” Andrés the maître d came out and shrugged, hooking his thumb back at the men’s room. Emi whistled the car-wash brigade into puke-patrol mode, and they descended on the men’s room and set out to make the rounds of neighborhood bars for which wait staff from the Tapis to the Alméndrigo were appreciative, the staff quick to contract out the dirty work for fifty bolivianos a pop.

“Also, Chepón didn’t show up…think you can throw one of your guys at the dishes again? We’re really slammed.”

“Take over while I get a jump on them,” Emi told Chapo, “till little Simon gets back and send him in to spell me.”

“No way, Boss; I won’t let you,” Chapo sighed, trotting back to the kitchen to doff his leather jacket to put on the apron and get to scrubbing.

Emi shadowed a couple punks clearly casing cars and looking for trouble and caught up with them.

“Pradero turf,” he advised them. “This is all under claim, and you’ll get shot if we catch you stealing or robbing or raiding or anything here. It’s just the way it is, my young pals. Friendly advice.”

“That sucks,” said one.

“But hey,” Emi said. “Over on Avenida Dos it’s a real mess over there, holes everywhere, their little syndicate all in disarray, and they got those boutique cafes with lots of fancy cars, plenty of soft targets.”

“Yeah?”

“But don’t come through here again unless it’s to apply for a job, or we’ll have to work you boys over.”

“Okay, hey thanks for the pointer.”

“My pleasure, good luck.”

With Simon back now and in the kitchen, Chapo and Emiliano gaged the progressing drunkenness over the half wall of the restaurant. It was ten at night and only a handful of tables still had food, the rest turned over to beer and dice, a few more sedate, older men together, smoking cigarettes over quarter bottles of whiskey and soda, a few holdouts tippling pisco. Four tables were openly raucous, possible trouble later on, but for now they all stayed behaved.

“Hey,” Chapo pointed down the street. “Will you look at that?”

It was six Avenida Dos kids, including two from this morning, Little Killer notably absent.

“How’s about it,” the delegation head looked up at Emi, after stepping forward to shake his and Chapo’s hands and introduce himself. “Gato Chino says to come see you. We’re done with Carriles and all the Avenida Dos drama. We’re looking for a real boss.”

Emi looked over at Chapo, who shrugged an ambivalent assent.

“You keep one third of what you earn,” Emi explained. “I get a third, and the syndicate gets a third.”

“The syndicate?”

“Yeah, and all of you get a share.”

“What do we gotta do, when can we start?”

“Meet up at nine in the morning in the median for assignments. Three of you will work day shifts with me. You three,” he pointed out the oldest, will pull evening and night shifts around the clubs. Carriles know you’ve split with him?”

“If he don’t he’ll figure it out soon enough. He’s drunk and raging. We’ve had enough.”

“Get on out of here. We’ll talk in the morning.”

“Emi, Carriles is going to figure it out, and he’ll come after you to have his revenge. It’d be best to go put him out of his misery tonight, right now while he’s drunk and raging.”

“Nah, looks like he’s done. If he’s smart, he’ll high tail it to Santa Cruz or La Paz and lay low to nurse his wounds. If he tries to tough it out let someone else take the heat.”

A commotion from inside drew their attention to the restaurant. “Looks like trouble,” Chapo smiled.

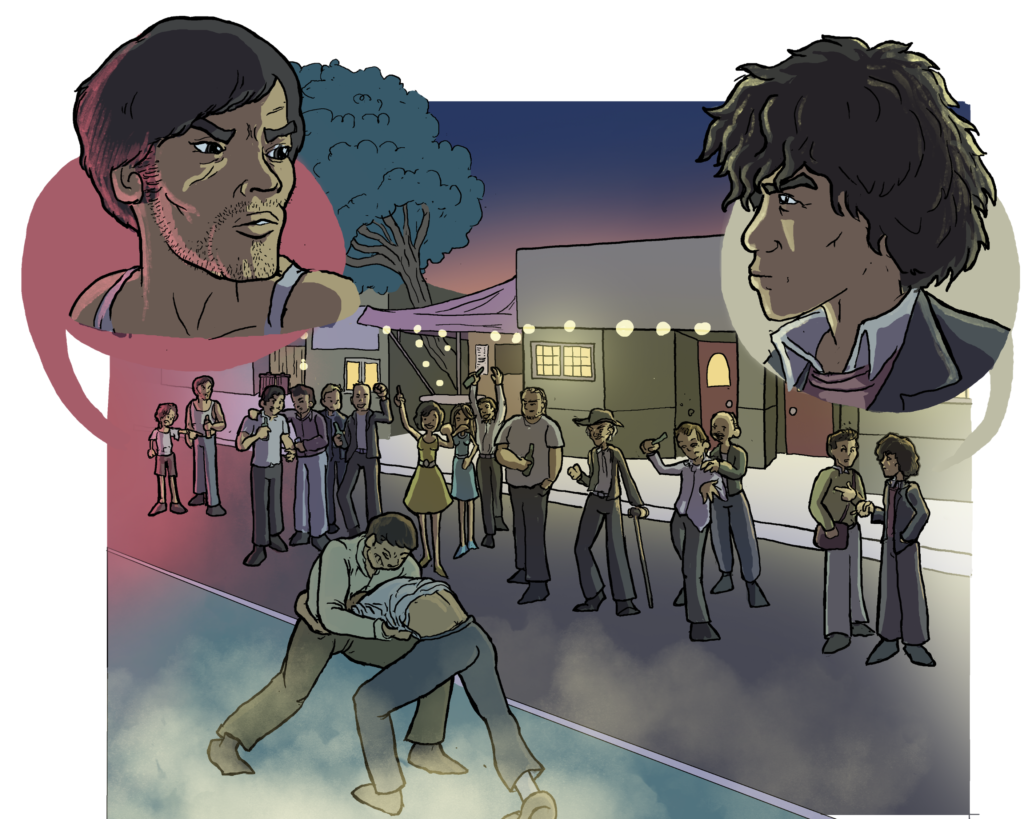

From the largest table the drinkers were all standing and arguing, all of them young, high school or first year university kids. Waiters rushed over to urge calm, but the principles weren’t having any of it. Elmer Vindas, a younger son of the Vindas clan about Emi’s age, reached across and put his finger on the chest of the foreigner who looked a bit younger but strong and stout. The foreigner slapped the finger away and fanned his own fingers to dare his opponent over. They were all friends at the table, but nobody was intervening to back their buddies down, drunk enough after their hours of drinking to be spoiling for action. Vindas reached across to make a pass at slapping the foreigner, but he leaned back and easily avoided the blow, though nearly losing his balance in the process. .

“Into the street,” Vindas pointed. And into the street and across to the median the congregation boiled.

“Hey,” a waiter yelled out, his bow-tie all bent. “The bill. You gotta pay.”

“Go pay,” Vindas told his second, leading the way out to the fighting ground.

The second belligerent, the foreigner, was all puffed up and staggering drunk. He didn’t seem to have a second, though there were three other foreigners in the group of eight pals assembling for the fight that would surely qualify as a second. Still, nobody stepped forward.

“Elmer’s gonna clean that kid’s clock,” Chapo pointed out as he and Prieto drifted with the gathering crowd to spectate.

“I don’t care how rich they are,” Emi said, “they’re going to need one another, and their old men probably do business together now and here they are like dogs, demeaning their ranks like this for the sport of all these shit heels standing around to watch someone get the shit kicked out of him.”

Emi spat on the ground.

“Maybe Elmer will go easy on him,” Chapo guessed as the two squared away and crowd began to hoot and yell.

“He’s got skills,” Emi objected. “He’s gotta know it ain’t fair and ain’t right. I hope he gives the kid a pass.”

And sure enough, Vindas seemed set to wind it down and reached his long arm out to grab his opponent’s shoulder as if to shake some sense into him.

But the foreigner pivoted and landed a roundhouse left hook and followed with a right cross and Vindas was tagged twice hard and stumbled backward.

“What do you know,” Chapo said. “We got us a little boxer. A tough little rich kid.”

Elmer shook his head and pulled a finger away to look at the blood from his cheek and turned to narrow his eyes and put away mister nice guy. The crowd roared. The foreigner danced around, sloppy under the beer, and Elmer stalked and used his long arms as the foreigner wasted energy on wild swings that did not connect. Next thing, Elmer had the kid in a head lock and off his feet and landed on his chest, knocking the wind out of the kid’s sails and started wailing on him and finally pushed himself up and away to brush himself off.

The crowd urged the foreigner to stay down, but he got to his knees and then to his feet and lifted his fists up to then wave Vindas back in. Vindas looked over at his second, grim now, all this beyond where it should have gotten. The boxer’s charge was sloppy, and Vindas stepped aside and kicked out and pushed him sprawling onto the grass.

He yelled something at the prone foreigner in their language—English, Emi figured—surely telling him to not get up, and when he found his knees, Vindas kicked him in the ribs and he collapsed on the ground and curled into a ball. Vindas walked around him, ready for another coup de grace. But it was over, and the group splintered, the Vindas contingent speeding off in a Peugeot and Audi, casual fight watchers drifting away now, a group of two from the drinking table standing over the little boxer awhile before shrugging and wandering off. After a few minutes all that was left was the kid crumpled on the ground.

“If I ever lose a fight,” Chapo said; “that’s how I want you to leave me, just like that, for the condor to come have his choice of which of my eyes to pluck out first.”

“The great ruling class,” Emi shook his head. “They’re just going to leave him for one of our kind to go roll him and get another couple of kicks in, perhaps slit his throat for kicks.”

“I would not put it past Little Killer,” Chapo said.

“Go get a bucket of water for me,” Emi told him, “and a tall glass of clean water. We gotta scrape him up and get him home to his momma.”

“Hey kid,” he kneeled down over the prone body, “you understand Spanish?”

“Yes.”

“You know where you are? You know what happened?”

“Yes.”

“Can you sit up? Let me help you. Let’s get you cleaned up a bit. Chapo,” he motioned.

Emi pulled the kid upright, squatting around him, and used his thigh for a back rest for the kid and sponged dirt and grit from the combatant’s face.

“I gotta throw up.”

Emi let him throw up and gave him clean water to wash his mouth out. “Put your head in the bucket to freshen up.”

The kid obeyed and slung his hair like a dog and found his knees, and Emi and Chapo helped him to stand and eased him over to a park bench where they sat the kid down.

“Where do you live,” Emi asked him. “We have to get you home.”

“There is no name for it; it is high above the Santa Colonia neighborhood.” The foreigner looked up and pointed to the northeast. “I live in an old manor on that side of the mountain, above our house there is nothing, no more houses.”

“Hey Prieto!” Sancho Carriles yelled in the night, stumbling up from down the way. “We gotta talk, you son of a bitch!” He slurred his words, still 75 meters or so away, Little Killer on his heels as backup. Chapo jumped up and strode toward them to run interference.

“Careful they’re not packing,” Emi said.

“Kid you got any money for taxi fare?”

The foreigner reached around to check his wallet. “My billfold’s gone. I’ll have to call my dad.”

“You can’t call your dad, little pana, drunk after midnight, brawling in the street with your pals.”

“I can walk. Help me stand. I’ll get myself home.”

“Put your arm around my shoulder,” Emi commanded. “Walk with me.” He was better after ralphing and washing up; probably wouldn’t pass out. His eyes were wide; the kid knew he was on shaky ground and was sizing it up. Emi whistled and Francisco trundled out and started up his cab.

“Get this kid home; it’s somewhere weird up above the Santa Colonia District.”

“That’s the bunghole of the universe, Emi.”

“Get him home. Keep him awake so he can guide you the last part of it. Here’s three hundred. If it’s more then you see me tomorrow, and I’ll catch you up on the balance.”

With the foreigner taken care of, Emi strode back out to the median where Chapo and the sad remains of Avenida Dos were huddled warily waiting on him.

“They’re clean,” Chapo announced. “Just knives.”

“What do you want, Carriles? You shouldn’t be here. You’re smarter than this.”

He was wild-eyed and drunk, Little Killer glaring through black, closely set pig’s eyes.

“Square up, Prieto.” Carriles tossed his knife on the grass. “I want a piece of you.”

“Ain’t gonna happen, Carriles. You gotta go sleep it off and put your thinking head on. It’s one o’clock in the morning, and there’s bad company settling all around us, folks I don’t control. I can’t guarantee your safety.”

Carriles staggered forward and swung wildly but missed and stageredf to avoid falling. Emi didn’t even have to dodge.

“Teach him a lesson, Emi,” Chapo urged. “Show him who’s boss.”

Emi turned with a flash of anger on his partner but settled himself. “He’s already had his lesson. Come on,” he grabbed Chapo’s arm and turned to walk away. “Let’s hail a cab and get outta here.”

‘We got a big day coming up tomorrow.”