Andrea Mitchell y Yo

All along I lied, telling myself it was just a game. But I have never breathed a word of it to a soul and now at 54 years of age it’s a reservoir built up behind me with a life time of water, charging the spillways, waiting only for the big rain that now threatens each workday as I grow closer to the calamitous attainment of my unholy grail. Gail knows that there is something wrong—has for some months now if not years, surely—but she has no idea of the gravity, suspecting surely it’s just mid-life foibles that I’ll get over if she leaves me to it. Oddly she was there at the very start of it, thirty-eight years ago, when my doom was set intractably in place by the most inauspicious and innocent of possible beginnings. Even way back in High School in the bible-thumping Appalachian hills from which we hail, I never believed in predestination; in fact, though I have never been brave enough to admit it, I have never even believed in God. I knew from as far back as I can remember that each person is the architect through choices he or she makes of his and her own future—that we drive and control the lives that we make—that I am and have always been the master of my destiny. How ironic that a lifetime later I have walked for decades down a robotic path from a choice I made as a junior in high school that came to grow around me like gentle ivy creeping up a brick wall into the windowless room into which I have never allowed a single soul—until this writing—to ever glimpse. What I always soft-pedaled to myself as a game has always been an obsession, one that has dangerously driven either directly or indirectly my every decision in life and propelled me to this awful abyss that I now stand before in a great swan dive poise, hungering for the rocks of perdition on Fifth Avenue below at the gates of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, insisting they are instead a pool of bubbling elysian hot springs brimming with the dryads and nymphs of love’s final attainment, my perverse folly. I look out my window, Central Park to the northeast a few blocks, downtown concrete canyon lands all about, and my office is lovely, a corner one on the 75th floor of the GE Building, and my rise to this perch has been steady and well rewarded. Gail and I have a place on the west side, paid off years ago, and the kids are beyond college, Ben with a mid-level management sinecure at Google’s Mountain View campus, Adam rising in investment banking through a knack for people, a Columbia MBA, and his closet of silk suits a hundred blocks southwest of here in his thirtieth floor office at Goldman-Sachs. We have time shares in Vail and Cabo, a brimming portfolio, loads of cash, and Gail is retired from a five year stint at MOMA and still brokering art on the side and distracting herself from the turbid yawns of menopause with charity work and dinner parties and her reading club and merengue lessons, and I mostly get my pick of production gigs here at NBC and our affiliates and contract work as I pick and choose. I certainly could have let it go at reaching this dizzying juncture and counted my blessings without taking that final push on the age old fetish-cum-game to get the job I had gamed for from the start all along, one I did not get to pick but had to politic for and politic hard but which I have now landed nevertheless. And here I am, gazing daily upon the fruits of my Mephistophelian bargain as executive producer of Andrea Mitchell Reports, the near-culmination of a deeply secret lifelong aspiration to stand before a final and fearsome bifurcation in my and Borges’s famous garden of forking paths.

***

“To those who much is given,” Ms. White gaveled the class to order with her fly swatter, “much is expected. Luke 12:48.”

I was sure that she had looked at me, but it was so brief that I could’a been wrong, and studying it over later after school, she may have looked at all of us in turn; hell, there was only eight of us sitting in the classroom. I figured I had made a big mistake with this AP Journalism business. They said I was gifted and talented on account of my grades and all, and I figured if I couldn’t cut it in the pros I would need something to fall back on. I’d always had a secret love for writing and in particular for investigative journalism. Pops he urged me on, surprising given he had always held out for me to study mining engineering. He was a coal miner and wanted me, Jamie, and Fred Tom to go on and do better. Course, he was doing pretty well, making near twenty bucks an hour, union wages, but good enough to keep us all clothed and fed and the mortgage paid. He sat me down the morning after my first drunk to lecture me hard; weren’t good enough for me, goddammit, drinking and carousing like there was merit in it, and in an unusual moment of clarity as my hangover subsided, I actually got it. Mom was college-educated but brought us up from home and only took to substitute teaching once Fred Tom was in fifth grade and me and Jamie was grown up enough to start feeling our own oats a bit.

“You may think that sitting here in this classroom,” Ms. White declaimed contentiously, “that you have attained something. Well, you have,” she acknowledged, swatting a blue-bottle fly that perched inauspiciously on her desk to meet its maker. “What you have attained for the duration of this year—or until I drive you from this classroom—is a great wake-up call that will, if I am successful, leave you bruised, broken, smarter, and hungry before a world that will for years to come consider folks like you and me from our beloved Bristol to be hayseeds and hillbillies, great fodder for the ranks of Mini-Mart managerial staff and Wal-Mart greeters but doubtful material for the likes of the Wall Street Journal and Washington Times.”

We had never been treated like this. We were all of us sitting there darlings and prodigies, and I rightfully suspected that a cassette tape of her words played before the School Board would be unkindly received. It was such a small class that we dared not grumble and move around, yet we did a little bit, and I glanced back and locked eyes with Gail Carmichael sitting in the back corner, all insouciant and self-contained, and she must’ve been waiting for me to look, for she lifted her eyebrows at me and I reddened in my whip-lashed return to attention above the hickory woody that rose in my lap.

“Tonight,” Ms. White declared, her fly-swatter a mighty scepter raised into the sultry stillness of the afternoon air, “you WILL read this week’s leading article from Time Magazine and arrive tomorrow prepared to make a comment about what comprises the grit of the man that wrote that article about this year’s candidate for the presidency, Jimmy Carter, that allowed him to let loose such lyrical cannonades of journalistic rhetoric.”

Daddy was a Nixon man, chastened by all that had happened a couple years ago in what was my own journalistic awakening, and I was quite sure that Gerald Ford was going to go on to win the election, and I felt a flush in my face at the effrontery of something I felt lurking and unspoken in words that I measured as provocative, but the tent in my lap calmed my spirit down, and I doodled in my notebook instead of piping up.

“Tomorrow,” Ms. White continued softly, her fly-swatter now subdued and resting by her side, her killing arm now limp in the heat of the August afternoon, “you shall return, each of you, with the name of a cherished and favored journalist of national stature. You shall write the name of this journalist down and fold the paper into tiny pieces that none may see and you shall drop these selections into Bobby Chatham’s hat—you will, Mister Chatham, present your ungainly Stetson for tomorrow’s class at the peril of my considerable wrath—and you shall each draw a name from the hat. You shall follow the professional exploits of the journalist you pull from the hat and present to me a term paper due December 5th that shall detail your impressions of that luminary’s journalistic advances during this fall semester. The term paper will comprise exactly 50% of your grade, the remainder a culmination of two tests and pop quizzes to ensure you keep current on your reading assignments.”

“Ever heard of secret Santa?” she challenged the class. “Iff’n I get even a whiff . . . “ She killed another errant fly hovering about her desk, catching this one in mid-air to smash its guts on her desk, “that you have revealed to others in this class what name you place in or draw from Mister Chatham’s famous hat, then so help me God you shall receive a big fat “F” at the end of the semester and will be booted from the gifted and talented of this here school back down into the pedestrian and mundane.”

She walked up and down the few aisles of the classroom and stared at each of us in turn. “Do I make myself clear?”

The next day I drew the name that was to guide all my intervening years. In tiny crimped writing that I could not make out without help from Ms. White, the name that I had drawn was that of a budding luminary of my secret world then unknown to me. The script revealed my perilous future in two tiny words: “Andrea Mitchell.”

***

My conversion to the Jewish faith was not as painful as that of Sammy Davis Jr., or others before me that surrendered their weenies unto the guillotine. In keeping with the conventions of the day of my 1959 birth, I was already circumcised, so really, I had it easy. Many are the times since I wished it had been otherwise. Perhaps had I been required to actually dismember myself I would have done the math to devise the gambit as beyond the right and proper. But I was given a pass on real sacrifice, and I was able to convert to the Jewish faith in my sophomore year of college in the great city of Richmond without any unduly raised eyebrows. Of course I did not patronize a temple and pursued my new faith quietly from my dorm room, hidden from my teammates and college pals. I will admit that I did not launch into it with religious fervor. I merely read up and tried to practice its arcane rites as best I could manage on my own without courting any particular spiritual upwelling in my soul but as a practical matter. It was common knowledge that to marry a Jewess, one could not be a gentile—far less what I did not then recognize myself to be: an actual atheist—and as part of the dynamic of the game unleashed three years earlier, I prepared myself spiritually for a path that would not be incompatible with a possible eventual marriage to Ms. Andrea Mitchell, for whom my heart and soul now pined with devotion and ardor.

But it was not until the year afterward that I took a bigger step in the direction that has led me to my momentary precipice high above the unforgiving streets of midtown. It seemed innocuous and logical at the time, though how today I rue the day! I was a pretty decent linebacker and had ten sacks my junior year and four interceptions, one of which I ran back for a touchdown. Boys around me quavered at the academic challenges but to me it was nothing. I made solid B’s with way more A’s than C’s and didn’t even work that hard. My athletic scholarship was never in question, neither from underperformance on the field nor in the classroom. But it didn’t take any rocket scientist in me to see that I was not fully on any par with the collegiate defensive standard-bearers of my day, and in a deep revelation one night on the 9th Street Bridge, catalyzed by Peppermint Schnapps and a reefer of Colombian gold as I pondered the murky waters of the James River below that I wasn’t exactly NFL stock. My coaches whispered to me of a second or third round draft, but on that bridge I cut to the awful chase burbling out of the black water below to downgrade myself to fifth or sixth round at the very best and knew that without throwing myself more fully than I knew myself capable into the full grit of it, that I’d wind up getting cut and thrown out on my ear into the cold. I might play a season or two, or maybe none at all, and I might get a sack or an interception. But on that awful bridge that awful night I seen that I wasn’t going to be no all-star, and it was an awful bitter pill. But choke it down I did. At least I was getting my way paid through college, not a mean feat by any means for a Bristol hayseed.

And that night, now moved out of the dorms into an off-campus apartment with my own private bedroom, Andrea Mitchell suffused my lone window in my Schnapps and reefer madness with a pervading blue light, and I saw that I must move on from my professed major in investigative journalism to a new major in news production. Ms. Mitchell beckoned it of me for only in that way might I lumber professionally into an intersection with her in which starting from a thirteen year lag in age I might finagle myself into her company as an approximate equal, perhaps—far be it for me to presume the possibility—in some relationship of control and power that might provide me a venue for sidling up to her great journalistic prowess, something for which she might find herself appropriately grateful, a modest steppingstone from which I would find the path to make her my wife, assuming of course she saw the light to remain decently unmarried and nominally available to my ignoble ambition.

***

All these years later, I have had many reflections upon that night on the bridge. In my darkest hours of self-doubt I have speculated that a specter overcame me to subsume my greatest light and settle for seconds. Many times I have blamed the Schnapps and marijuana for the befuddlement that in a single moment diverted my career path from that of a great professional athlete to the minions of unsung functionaries that settle into and perform lesser careers. Today as the street below me alternates with boulders of perdition and thermal waters of attainment, I cannot help but wonder what might otherwise have been, and I trace it all back to the view of black waters flowing beneath me as the handful of cars passed back and forth, oblivious to my great life-quenching moment of betrayal and revelation.

But you can’t easily fool the world toward merits you don’t really have, and once my sights were set I saw clearly that without a master’s degree I would not have the full set of necessary tools to adequately exploit this alternate reality conjured from the burbling black waters of the James River. I was awarded a graduate research assistantship at the prestigious Johns Hopkins University and granted a free hand in the university production studio just as MTV burst onto the scene to shift the paradigm of my pogo-dancing new-wave generation. I watched Video Killed the Radio Star over and over for days on end and recognized in that crude video the pole-shifting intersection between investigative journalism and media as a saddle upon which I would ride the bucking-bronco world that would be my oyster. People speak of “tiger’s milk,” but for me it was more like “yeti” or “bigfoot” milk, and my athletic aspirations became a toddler’s outgrown pacifier, and I folded my entirety into the blossoming field of news production that I was for the first time in my life what I factored as the forefront of the known universe.

When I looked up in the Student Union from my rushed together story-board for a special-project expose on Iran-Contra to find Gail Carmichael observing me from across the dining area with her faint smile and poised French fry, it was like that night on the bridge, and we were married within the year, and I jumped at a production manager berth at the university station that would allow me to defer my graduation by a year with full pay to time our graduations together. She was in the MFA program and painted watercolors nude from the balcony of our cramped married student housing and tried her hand at cooking and cleaning as I spent greater hours with the expensive and fancy equipment in the university studio. Then it was still all mostly analog, but digital methods were popping up all around, and I knew better than to not get on them like a duck on a June bug, and to my credit, I worked hard and developed considerable skills in the full range of the technology in use and coming, talents that would serve me well in years to come and have proven to comfortably feather our nest. When we attended graduation and tossed our mortarboards, Gail was six months pregnant and NBC Nightly News a fixture of our nightly routine. Andrea Mitchell was then the Chief White House Correspondent and in the eventful final years of Reagan’s presidency had a spot nearly every night on our television set, reporting less than fifty miles from where we emerged from graduate school to look around upon the wider world beyond.

***

I landed a job with NPR and we rented an apartment in Silver Springs. Ben was born in September, Adam two years to the day later, and Gail did not venture into the workplace for a full decade until Adam was in elementary school. I put a deposit down on a two bedroom in Vienna in December, 1987, and presented it to Gail as a Christmas present that year. In the early years with three mouths at home to feed and all the trappings of middle class success to sustain and my own yearning to not just succeed but to excel in my trade, I might well have forgotten altogether about my dark and secret game. And for a while I did. In fact I recall Andrea’s promotion in 1988 to Congressional Correspondent with NBC News as the first marker in her career that did not make me giddy with excitement, for which I was not compelled to manufacture an excuse to celebrate with Gail. Of course we watched the broadcast religiously, and I still hung on every word she breathed during all her reports, but the intensity of my obsession waned, and as Gail grew more and more lovely in her motherhood, my love for her and pride in what we were achieving surpassed the impact on me of my silly little long-running game. It was in 1991 when I was offered a staff position with CBS that would mean a move to New York, and I was by then pretty sure I had beaten this thing undamaged when a bizarre revelation pushed me as near as I have ever come to confessing the whole thing to her.

It was during the immediate run-up to Desert Shield as the forces of many nations converged on the Middle East under the aegis of Stormin’ Norman Shwartzkopf. Gail had taken to following CNN’s continuous coverage during the day, switching over to NBC only once I got home to follow the local newscast at six and then NBC Nightly News with its stalwart Tom Brokaw at the helm. Truth be known, I was deep down a Peter Jennings man, but Andrea Mitchell was not a correspondent for ABC World News, and I came to admire Brokaw very much.

“I guess we’re going to have no choice but to switch over to Dan Rather,” Gail bemoaned the downside of my new job.

“Ooh,” I groaned. “You think?”

Naturally, I had already thought of this and gotten beyond it. With VCR’s and automation, I could watch one program and record the other to watch later, so I knew I had my out. But I was hardly going to share this with Gail as it strayed too near the nebulous boundaries of a sickness in me that I would keep secret at all costs.

I clicked the remote back and forth between the two newscasts as we compared the styles of the two anchors and the kids played on the floor.

“What would your new bosses think, honey” Gail grinned, sipping her obligatory six-thirty Chardonnay, “if they caught you watching the competition?”

Andrea’s face filled the screen, and I could not bring myself to surf away from her intelligent voice, her aquiline nose, and the puffy lips that chewed words and returned them changed from the speaker set, conventional words that in her pronunciation were now new things, bedecked with multiple meanings, dripping with a sensuality that fell from them to moisten the air of our living room.

“I am sure going to miss my Andrea Mitchell,” Gail said.

The world stood still in her odd pronouncement, and I was sure I was somehow busted, that the statement was a trap to draw me out. I let it hang there and finally braved a comment, careful that the modulation in my voice did not reveal the horror I held in the subject matter of our pre-dinner conversation.

“She is pretty good,” I acknowledged. “But the real sacrifice is Tom Brokaw. I just can’t stomach Dan Rather.”

“I remember when she first appeared on WTOP as the local news anchor,” Gail went on. “Daddy would go on and on about her New York accent, about how out of place it was for a DC anchor, but I thought from the start she was pretty and smart and independent and a great example for young women. She was my idol back then . . . ”

“Really? Not Barbara Walters?”

She scowled at him. “Barbara Walters? Puh-leaze.”

“I had no idea,” I replied, switching it back over to CBS as Andrea’s segment finished, eager to drop the subject.

“Don’t you remember Ms. White’s class?”

“Of course, honey; I’ll never forget you drawing up the rear, all sultry and vampy, the walking fantasy of all us boys.”

“Well, I drew Geraldo Rivera,” she announced. “I guess it’s safe to own up after all these years. Ms. White probably wouldn’t mind; she certainly can’t give me a ‘big fat ‘F’ anymore.”

“Ew,” I replied. “Surely not Geraldo . . . who would put his name in the kitty?”

“Be fair, honey, he may not be a tower of journalistic prowess and integrity, but he has a lot of character.”

“Sure he does.”

“And he’s kind of cute.”

“If you say so, I guess, in a greasy kind of way.”

“Who did you draw?”

“Oh honey, it’s been so long ago,” I wavered.

Gail registered surprise. “Oh nonsense,” she replied. We spent months on that assignment. “Surely you remember.”

“Oh yeah, that’s right. I drew Walter Cronkite,” I replied. I had never before lied to Gail but my heart was racing for other reasons, and it would take me months to assimilate this casual and awful betrayal. In fact, I had put Cronkite’s name in the hat, but Ms. White had forced me back to the drawing board as another student had already submitted him. In the end I had scrawled “Dan Rather,” hurriedly and always recalled it as an uninspired second choice. The whole thing about lashing himself to a telephone pole during Camille caught my fascination as a kid, and I am sure I was not alone. But that was about the last inspired thing he had done, and I had re-watched his 1988 tongue lashing by then Vice-President George Bush over and over again, smiling and laughing at how the old patrician turned him to hamburger there on his own show in front of the whole nation. I was a yellow-dog Democrat in my old man’s mold, certainly no friend of Bush, but I sure did get a kick out of seeing old Rather get smacked down so ugly, his nose all rubbed in doodoo like that.

“I always wondered who got my pick.” Gail would not let it go. “Andrea Mitchell was not exactly a household name back then, and I was surprised the Ms. White allowed it to stand.”

“Let me get the dishes tonight, babe,” I offered, bounding up from the table and busying myself to change the subject and divert the nervous energy dancing around me in the room.

***

The real estate market was on fire, and we made an obscene profit on the Vienna house and were able to put a down payment on a cute townhouse in Greenwich Village, and I doubled down on my work as the kids started school and Gail put her housekeeper’s apron away and landed a job in sales at a little gallery on Times Square and we split the household work more evenly so she could spread her wings.

But it was more than a coincidence, far more than an irony, and I was never sure whether she in fact knew more than she let on and always worried that it was a trap. But of course I simply could not broach the subject, and I stewed on it for years. On my way to work each morning on the subway I often retraced the history of it and came after a few months to settle on the explanation that it was a kind of accidental sorcery. Gail had a thing for me in high school and in her unperfected feminine wiles she had managed to put her love potion on that little piece of paper that I had drawn from the hat. Only in the immaturity of her bewitchment, rather than Gail, it was Andrea with whom I became hopelessly smitten. Yet years later I had looked up at her French Fry waving smirk in the Student Union and the rest had been ordained, like a set of dominos knocked down, and now we were happily married with children, perhaps her secret objective all along, and somehow Andrea Mitchell had been the great catalyst for that to happen. It was a maddening association, and I grew angry and resentful at having my own free will bent against me and manipulated for Gail’s selfish ends. We went through a couple rough years before I started to get over it, a time period where I spent more time with the kids and many nights on the couch. But the more I mulled it the more impossible it seemed and there was no such thing as spells and love potions and witchcraft. It was all a monstrous and ironic coincidence, and as I emerged to this realization I drew Gail and the kids all the more tightly around me and worked harder and spread my résumé around and got a huge break, not the long-desired offer with NBC, but six figures to run CNN’s New York production operations, a major career break, and I gave notice at CBS and permitted myself again to openly dislike Dan Rather, and we got a favorable offer on our place in the village and two days later signed a contract on the three bedroom on the West Side, where the master suite had a veranda and huge picture window looking out over the Hudson.

***

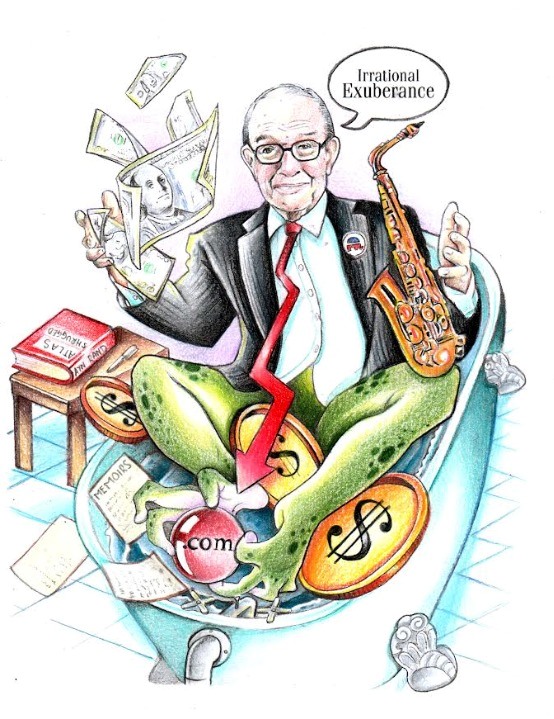

Nineteen ninety seven marked the beginning of a lost decade for me, a period that I spent floundering and hateful, eager to buck the conventional wisdom that was so widespread in the day that I came to be viewed as a heretical outsider, a cynic and petty naysayer. But during that time I carried my virulent abhorrence of the apocalyptic world order to new levels in my work and was lauded with a number of awards for my new penchant for documentary radicalism. I so came to hate Alan Greenspan that my world turned upside down and I began to drink and talk to myself long into the night. It was April 6, 1997, when my world fell apart. Ruth Bader Ginsberg, a judiciary hero of mine, officiated at the ceremony across town, and I was stunned to learn my world had been turned upside down when the news spread across midtown and CNN scrambled with its reporters to cover the aftermath. The ceremony was private and undisclosed in advance, and it came as an awful shock as I took stock of the dramatic uphill battle I now faced. How in the world was I, a mid-level executive, to ever compete for Andrea’s affections with her new husband, a man it turned out she had been dating for nearly fifteen years, the revered Chairman of the Fed, one of the most powerful men in the world?

I moved through the early days in a trance, forcing myself to work and then collapsing at home on the couch to sleep through the evening hours and then drink into the night. Gail mostly ignored me and the kids left me alone, and it was three months before I could snap out of my self-pity and chart a path back toward redemption and into renewed competition. I had not played this game for twenty years to now be thwarted by even this challenging development. The problem was that the man was godlike in those days, widely admired by all hues of the political spectrum. I had never before taken a hard line against Ayn Rand but went out to buy Atlas Shrugged and reread it with vehemence toward all that it represented and took on Greenspan’s early advocacy of her philosophy, back before I was even born. I signed up for economics classes at NYU in the Fall of 1998 and Spring of 1999 and courted friendships with brokers and investment bankers on the Street and delved deeply into the arcane field of high finance and macro-economics and took to following the ranting of Paul Krugman a decade before his Nobel as he peddled his liberal economics as an open pariah in those heady days as me and everyone around me made money hand over fist in the market.

My office sparring partners chuckled at the ferocity of my opinions, surprised at how a mild-mannered technocrat with modest political views could transform into such a virulent and outspoken critic of the universally admired and acclaimed Fed Chairman. As Y2K neared, I read tea leaves and yearned for a collapse of the global economy as computer systems failed and global finance slumped and the distribution of the blame would necessarily find Greenspan in its merciless crosshairs. When this did not happen, I redoubled my efforts to work slavishly on exposes in the early years of the new millennium on the series of high profile fraud cases from across town, the Arthur Anderson accounting scandal, ENRON, Tyco, and I ventured into dark restaurant corners from Queens to the Bronx to huddle with nervous moist-lipped whistle-blowers glancing nervously about us and struggled to formulate the line of attack to expose the great man as a gargantuan fraud. But it was to no avail, and the more I delved into high-finance shenanigans, the more the Oracle proved immune from my quiver of poisoned arrows. Yet I continued to win awards, along with the investigative journalists I cultivated for my projects, and there was a Pulitzer even in 2002 and a Taco Kuiper the next year.

Gail had done well husbanding wealthy clients from among my friends and their associates. She left the gallery to become an independent broker and put up and coming artists together with big money and collected large commissions that in 2004 actually exceeded my own earning power. She took an adjunct position in acquisitions the next year with the Museum of Modern Art. Meanwhile the kids did well in private school and excelled in sports and academics, and my dark years of patient assault coincided with a period of happiness and success for Gail and the kids, and I was left mostly to my retributive devices. Whether Gail saw through my shadowy persecution or not, she did not press me on it and I mostly behaved at our dinner parties and withheld my most strident criticism in check, determined to break out with a back-breaking scoop when the moment presented itself and not be dismissed in the interim as an obsessive and passed-over crank.

By 2005 all my colleagues were distracted by the messes of Iraq, Guantanamo, the Patriot Act, and rumors of black sites and CIA renditions and the universal decay of American prestige around the world and its impact on the Big Apple, still the world’s intellectual, financial, and social capital, and the glum prospect of the remaining years of Bush the Younger’s presidency. Greenspan continued to ride high and I finally threw my hands in the air at his utter invincibility. I had insisted for years that his holding of interest rates to the floor was unnatural to the economy and a dangerous trend. But all my buddies thought I was crazy, and we all made money in the market, raking it in as an indirect result of the Chairman’s championing of basement prime. His low-keyed storyline about the wars and threats of terrorism and the American economy’s sensitivity were widely lauded as sensible and forward-thinking, his inscrutable comments the clearest evidence of his unassailable genius.

I turned to exercise. Let’s face it; Andrea Mitchell’s husband, genius though he may have been, was a toad. I, on the other hand, now in my mid-forties, was a handsome and well-proportioned, virile man that turned plenty of heads in my sharp suits, my physique still nominally intact. I took to the gym with a fury and I ran in the New York City Marathon in 2006, coming in 345th out of the thousands of entries. I bought an expensive bicycle and raced around my west side neighborhoods. I quit drinking and cut out red meat and fried foods and to my family’s dismay pushed steamed vegetables and fruit at our table and rose before dawn for my workout and took a mid-afternoon break daily to sweat it out at the gym downstairs, and the health kick restored untapped reserves of energy and drive. I gave Gail merciless workouts in bed and drove my staff with a renewed intensity and dropped the crazy talk of the previous years and rose again in prominence for the balance of my views and my innate feel for the weak points and sense when to pounce to draw out the hidden sordid side of each of the stories that we ran.

***

My vindication came in 2007 and I sat back as colleagues flocked into my office through the weeks that followed Lehman’s collapse to bemoan their own abhorrence at being personally overleveraged at a time when the economy had been so vulnerable all along, just like I had been saying for years. Vindication turned to sweetness as the worm turned for the Great Economist. With the writing on the wall he declined to be considered for another turn at the helm, knowing his turn in the captain’s seat of history was over and the evolving verdict sure to be a harsh one. When he complained publicly that the Journal was set out to ruin his name, it reduced him to a tragic character, and I began to feel sorry for him and questioned the ferocity of my prosecution through the years. In the fallout from AIG and Lehman and Bush’s bailout and Obama’s expansion, I was tapped to produce the two-hour special that would unravel debt-swaps and securitization schema for the American public, and I convinced the network to parade our heroes through the piece, Larry King, Anderson Cooper, Wolf Blitzer, John King, Dana Bash, with Christianne Amanpour at the helm for the authoritative enveloping narration, and we knocked the networks back on their heels with a stunning 35/62 Nielsen share for the two-hour prime-time special. I ignored the flood of headhunter calls and was polite to those that stopped me on the street and stood down from the attention till NBC put their old standard-bearer, Brokaw, now retired, up to invite me out for lunch one day to discuss my future.

I signed on with the network and moved into my corner office in 2010 and made the rounds to get to know all the good folks there and see how I was going to best fit in. I was a professional at cloaking my intentions and studied the many proposals and pitches and was very respectful to all, extolling the hard work and insight of all my new colleagues. But I had my eyes, of course, on Andrea Mitchell Reports and did my background on the show’s production trajectory and current staffing, biding my time and keeping my aspirations hidden, releasing only suggestive crumbs piecemeal to my new boss, the Vice-President of Operations, laying them out in such staggered and intermittent succession that the idea, when it was finally out and under consideration, would emerge from his office, under his aegis, the whole thing clear of my fingerprints. When the time came, he would think of it as his own idea all along, my likely fit with Mitchell’s show.

My ten years in the wilderness were over. I had my mojo back!

***

I doubt that Nobel laureates actually aspire to that illusive prize, surely not in advance of being nominated. I know that men like Bill Clinton and perhaps even Barack Obama did aspire from an early age to a position so impossibly unlikely that the feeling upon attainment must surely have been analogous to my own the day, after thirty years of my secret game, that I finally met Andrea Mitchell. My boss set it up and asked me if it might be okay for Andrea to drop into my office for a meet and greet at eleven. As the clock ticked nearer the hour my insides warmed and I felt the empty wholeness that I have heard associated with drug addicts on the verge of a fix.

“Listen,” he said at the doorway to my office; “I’d love to join you, but Matt has asked me upstairs, and I’ll leave you kids to your own devices.”

“Mister Harris,” she smiled, stepping into my office to take my hand between hers. “I am so honored to finally have the opportunity to meet you. I have followed your career with admiration for many years.”

Her radiance in person so outshone her small screen magnetism that I stood dumbfounded, the coolness of her soft hands sending electrical impulses that lifted the hair from my head and caused my toes to curl. “I do hope that I am not taking you from more important business,” she smiled. “I’m sure that I am, but thank you very much for taking time out to receive me.”

“Oh,” I managed finally to smile. “Not at all, not at all, please come in.” I closed the door behind her and led her to an armchair where she took a seat and crossed her legs. I sat in the adjacent love seat and bounded up again at my thoughtlessness. “Forgive me, may I get you something to drink? I can make a fresh pot of coffee, and I have soft drinks and orange juice, or a glass of Chablis if you wish or a burgundy . . .”

“Oh no,” she smiled, patting the arm rest of my love seat, “don’t fuss over me, I am just fine.”

“Ms. Mitchell,” I controlled my irrational exuberance, “or Mrs. Mitchell, excuse me . . . “

“Andrea, please,” she smiled.

“I have followed your career since your WTOP days and I am honored and frankly stunned that I might have an opportunity at long last to collaborate at some measure with one of the gleaming luminaries of our industry.”

She laughed, and the sound bounced discreetly off the walls as she pulled the hem of her skirt over her knees and glanced down and then back up again with a coy smile. “That is unfair,” she shook her finger at me, “pointing out my age so inconsiderately.”

My obsession has never been sexual per se, and the end run of the game has never been some sordid romp in the sack. But her scent surrounded me, and the music of her voice enveloped my head. Her laughter was positively aphrodisiacal, and here she was, her slight hands folded in her lap, her full lips pouty in her smile, parted to reveal strong white teeth, her nose so pronounced and dignified on her thin face and bouncing tom-boy’s hair that she may have descended directly from Caesars, albeit by way of the Levant, of course. The room grew warm, and I felt my face glow with a redness that somehow was okay; I crossed my legs, and she uncrossed her own to re-cross them the other way and her skirt moved on her, the creases in her blouse folding in a new suggestive direction, whispers of silk, murmurs of flesh rising, pheromones filling the air around us.

“Stan,” she smiled gently. “If I may be so personal, Al and I were very impressed with your expose on all the financial collapse business. Of course it’s been hard on him, all of it very personal, but he was so impressed with the piece that he took the time to find out who was behind it and came to me the next day to point you out to me, that you would be a tremendous asset in anyone’s corner.”

“Oh,” I said, stunned.

“Now, I have been following your work for years and knew that all along. But I was pleased to have Al come to me on his own with this. Your piece of course was not particularly complementary to him personally—not that it should have been—but naturally I value his judgment a great deal, and I wanted you to know, because you might not realize it, that your name is a familiar one in our household.”

“Well, I, I, um, I’m very honored and flattered that you would tell me this,” I managed. “I have long been a huge admirer of your husband.”

She chuckled again and looked at me askance. “Now, now, Mr. Harris—Stan, no white lies please. It’s okay. Al’s a big boy and can take his lumps. You were a skeptic in this town when nobody else had such insight, far less the courage, to speak out so honestly and against such considerable odds.”

“Well,” I blushed, glancing down at my lap, beyond words. “Nevertheless I admire Mr. Greenspan nearly as much as I do you.”

Andrea Mitchell laughed again, and then waved her hand in the air to dismiss the whole thing.

“You’re a big shot,” she wiped the smile away, deadly serious now. “I’m just a working girl doing a gig the best I can. MSNBC doesn’t have an exactly Midan budget of course, and while I try to stay out of the business end of things, I stay abreast to the extent my tiny business head allows me of the financial mechanics of it all. We just do a show, low impact, routine, pedestrian. It’s a job,” she grinned, “not an adventure. Frankly I am surprised that a person of your caliber is even being brought in as a possibility for executive production. To what, I am forced to ask you quite frankly, do I owe such an extraordinary honor?”

“Uh,” I hesitated, floored by her words. “I don’t know, Andrea. My wife and I have always been great fans of yours and dedicated followers.”

“Oh,” she raised her eyebrows. “I see . . . so your wife is somehow behind this? I look forward to meeting her.”

“No, no, not at all. Look,” I finally found my voice and leaned toward her and wiped my silly embarrassed grin away and stared at her hard. “I just like being part of good things, and you are a good thing, and truthfully I could reverse everything you just said and lay it at your feet and argue that it is I that has the fortune to perhaps work with you and certainly not the other way around.

“Well,” she smiled. “Curiouser and curiouser. I will take that glass of Chablis now, and you can put a post-it note on the glass saying “Drink Me.” I think I need an antidote for how large you have made me grow this morning.”

I hopped to and we had a glass of wine and concluded our introduction. I dared not ask her to continue it over lunch, far too intimate for a first date, but I walked her to the door as she took her leave and took her hands in mine by way of departure.

“Mr. Harris,” she looked up brazenly. “I do believe you’re flirting with me.” She smiled grimly before turning to stroll insouciantly down the sterile hall.

I loosened my tie in her departure and cancelled my appointments and spent the rest of the afternoon in my seat gazing out my magnificent window over the vastness of wealth and privilege and forgot all about my afternoon workout and hailed a cab in a daze as a warm gentle rain settled across downtown and the canyon towers disgorged their beautiful inmates out onto the gold-lined streets of the immaculate city, still capital of the known universe. I headed home to give Gail a thrashing she will not soon forget, surprising even myself with the indignities with which I quieted her simpering moans.

***

“So I cannot get beyond the dichotomy,” I explain to the therapist that I have taken great pains to ensure nobody knows about, “of the gnashing boulders and thermal bubbling waters that I stand over poised to dive.” She seems to know her way around Google as she had me all placed on my second visit. Naturally, I have not divulged any names and have taken some pains to obscure personalities so that she doesn’t actually discern identities and leave me even more hanging out than I already am. “I keep it at bay by focusing on the work and stiff-arming my temptation to act on it. But it’s a terrible strain. She’s flirty and I don’t know how much longer I can control my impulse to sweep her up in my arms or something catastrophic and egregious like that.”

“Perhaps that’s exactly what she wants,” Rebecca replies.

She’s a brassy young Jewess, hot as an Alamo pistol, mid-thirties, boob-job, oozing sex, getting off, it seems, on my awful predicament.

“I’m not here for you to encourage me in my aberrance,” I complain.

“I’m just saying you can never underestimate the animal side of human nature,” she sighs, pushing her glasses back up on her nose. “It’s not too uncommon for grown men and women in this town to have affairs.”

Perhaps it is a perverse brand of reverse psychology, encouraging me to relax my internal safeguards against perdition, and maybe she is just taking my money, getting paid to indulge in a prurient voyeurism that melts her own weird butter.

“How does that possibility make you feel?”

“Like a character in a particular Nabokov novel,” I reply. “Like a predator.”

“Are you hurting anybody,” Rebecca asks. “Including yourself? Look, you point out that this new gig has brought both you and the object of your, uh, obsession, professional accolades. You yourself observe that the greater the sexual tension the more successfully you have been at changes in format and approach that have boosted ratings and advertising revenues . . . “

It’s true. I pulled an old trick from my bag and convinced Andrea and the bosses to let her grill her colleagues at MSNBC in spots on her show that have gotten good nods in this tough town. It makes me smile at how much she does not like Jim Cramer, but the fireworks when he comes on to face her on an investment spot gets the industry screaming with laughter, the audience begging for more. The bosses screamed bloody murder when I got Olbermann back for a cameo on his old network and had Andrea assume a contentiously conservative viewpoint. Poor Keith was thrown for a loop, left impossibly without a quick snide word in response at the apparent betrayal of a reliable coreligionist, but it made for good television and he was good natured about it afterwards, appreciative of any upside to his pariah-hood, and it’s nearly a shtick, now, several months into my tenure. Rachel Maddew was not quite so gullible, of course, and held her own well, but I think she may have a bigger crush on Andrea—if that’s possible—than I do myself. And Gail and I have been over to Al and Andi’s penthouse a couple times for dinner parties sprinkled with requisite celebrities and mover-shakers, and I’ve shared some modest chuckles with the old toad myself, and he’s not a bad guy at all, kind of funny in his lugubrious self-effacing way.

“You know, Mr. Harris . . . I enjoy your analogy of the rocks and thermal pools very much. It’s very poetic. But the deeper symbolism of the clinical issues, I think, is the bridge conversion back in Richmond. You backed yourself down through self-doubt from a promising career in professional sports to take on a “safe” but nevertheless challenging alternate career for which you were not natively destined . . . Don’t you see that you foreswore an easier path to claw your way up a much harder, less thankful one?”

It has of course occurred to me many times.

“I think that the ‘game’ that you refer to—your lifelong obsession with this woman—has never really been about her but a weapon you have created to bring out the very best that you can in yourself. And not to diminish your further capabilities, it would seem that you have been successful, and that you’re ahead in the game, that you’ve won.”

Oh but were it that easy.

“So it’s your burden. Bear it. Lift yourself through it. You clearly benefit. From my limited perspective, I can tell you that my clientele—all of them but the narcissists at least—would prefer your challenges to their own.”

***

Maybe so. Sex with Gail has certainly not suffered. And the raises and accolades keep coming. And I do agree that I am doing some of my best work and that it is easier for me. Yet the scent inside the studio as Andrea draws to reconstruct simple words as exotic enchantments in her bewitching accent causes the thermal waters to burble and boil, and the touch of her hand on my forearm to make a point is a rocky shoal that through infinite softness rends my body against unforgiving surfaces, and all of it combines into a tightly wound and stretching piano wire that before it breaks to lash my face and tear my body still produces harmonic tones of rising pitch that roils my viscera and keeps me raised up on tippy toes, sipping the rarefied air of a perverse and mundane reality above the ever-lurking shoals and pools below.