Un Ruso Mas

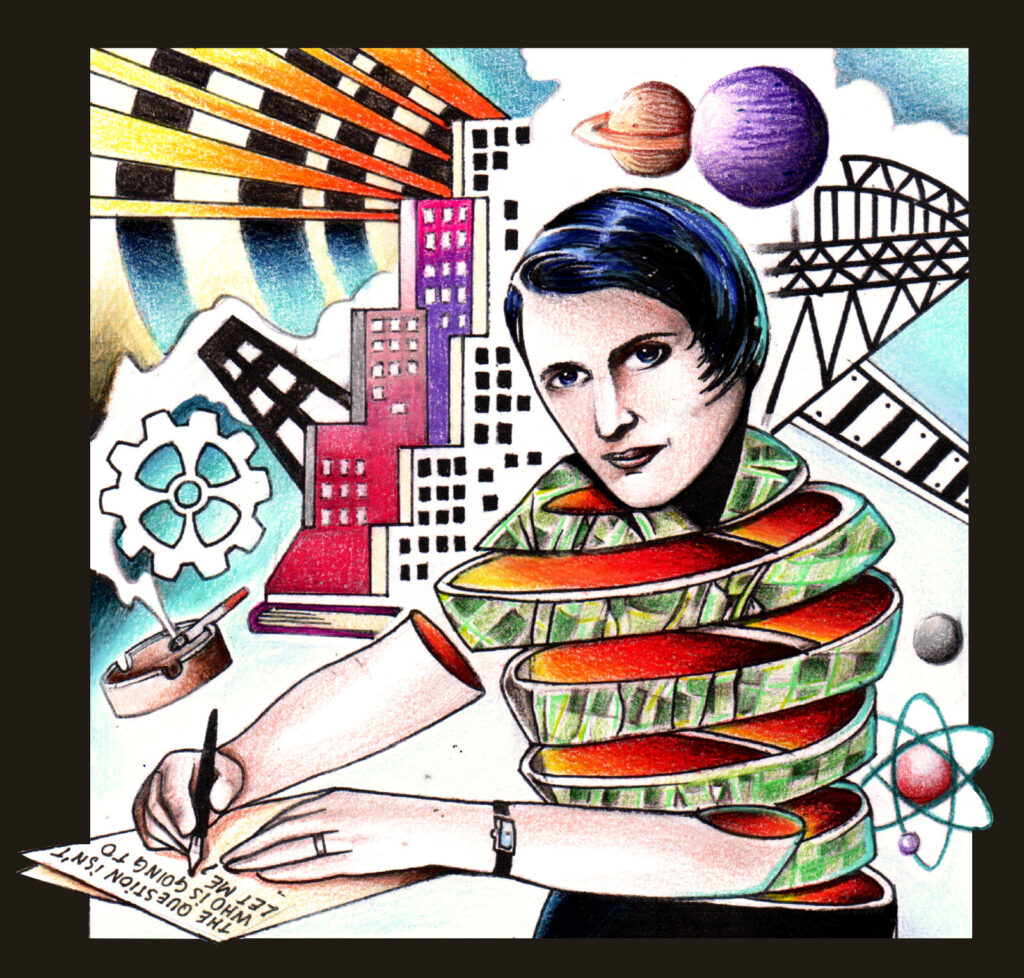

Jack Stone sat for the third night in a row on the terrace of the Beirut Restaurant. He smoked a cigar, drank a glass of wine, and ignored the menu. He read his novel and deferred his order to luxuriate in the gentle breeze coursing up Calle 52 in Panama City’s banking district. He had read the novel years before but could not place the era in his life. He was nearly to the middle, and though engrossed in the action, nevertheless weighed the option of tabbouleh salad, which he had enjoyed here on a similar trip the year before. But the night before last the Greek salad had been so good that he had returned last night to have it again, and on this, the final night of the trip, he was back again, an old dog. It was not that he was leery of something new. But across six trips this year, his dining experiences here had been mostly pedestrian, a few outright disappointing, all pricey. There had been the excellent Peruvian place, but beyond that his picks had been mostly let downs. And the tabbouleh had been very good that one time here, and would be very good again he was sure, and he decided when he was finally ready, that he would forego the Greek salad to order that instead.

The house wine was marginal at best, but he forgave it and tippled urbanely. He had bought the Cohiba from the Havana Club, a block away. The humidors there were filled with Partagas, Montecristo, Punch, Cohibas, and a few lesser and greater, though less well-known, Cuban brands, and they started at fourteen dollars for small ones. A cigar that he could buy back home for ten bucks here cost twenty, and he had politely allowed the attendant unbidden to recommend what the bow-tied man had called an “excellent” cigar. It was a maduro, with which he was acquainted, and he had plunked his twenty-four bucks down and gotten a free box of matches and clipped the end with the cutter on the counter to repair to the Beirut, where smoking was allowed on the great terrace that surrounded the colonnaded glass-plated interior and stood seven steps above street level. The terrace afforded views up both streets at the intersection upon which the restaurant was located. But here on the breezy terrace where the well-dressed and beautiful began to converge in greater numbers in the progression of evening, his cigar drew poorly and even once well-lit from the exaggerated puffing to get it decently going, it went out between puffs, and he frowned at it and set it in the ashtray and returned his energies to his book, deferring sips of wine to draw it out and prolong his calculated satisfaction.

The breezes that gusted up the street and under the ceiling blew off the Pacific and brought with them its heft, and in a city that could be stultifying by day, was cool and invigorating by night, and he was comfortable and relaxed in casual slacks and a polo. He had treated himself to argyle socks and Dockers for the occasion, leaving his Crocs to sulk in the hotel room. Needing to rid himself of his tobacco habit, it served him perversely right that an overpriced cigar refused to cooperate. It had probably been rolled in the Dominican Republic or perhaps even Honduras, but he refused to let his mood suffer and read more intently, letting his glance stray periodically to the entrance steps as unusually attractive women with stern faces mounted them on the arms of well-heeled men, young and old alike, mostly as single couples, occasionally small groups, and the odd family with a bored child in tow or a passel of them, chattering gaily. It was mostly an affluent Panamanian crowd, but there were many foreigners as well, a handful of Americans, some Europeans, and a few others clearly Middle Eastern. He caught snippets of English, French, and what he assumed was Arabic that drifted through on the breeze rustling through the friendly night. He smiled at the prescience of dining in a Lebanese restaurant in Panama that Lebanese nationals actually patronized, comforted by the certainty that the swarthy well-dressed exotic ones, like the group in the corner huddled around a hookah, were indeed Lebanese.

He had discovered the night before last that the wrought iron chairs with cushions and armrests did not all reach the same height with respect to the table surface, so he had moved from his first seat to scout out the options and had found one that was perfect. Last night that table had been vacant but the table behind it had been occupied by a vivacious young group, three women and a man, and though one of the women smoked a cigarette, he had chosen a different table to spare them the smoke from his cigar. But last night the surface of the alternate table loomed an inch higher than he would have liked it, and he had dismissed the unease this seeded in him only through a concerted effort. Tonight he arrived a bit earlier to find the surrounding tables unoccupied, and he had taken his favored seat. Unlike the forgiven wine and disappointing cigar, it was just right, the perfect seat, the perfect well-lit table surface. And the book, of course, was excellent, the night vibrant and alive, and he felt very good as he took the final sip of wine to glance up at a waiter.

“I would like an Atlas beer, please,” he smiled at the young man. He hesitated a moment. “And a Greek salad . . . and an Arab bread.”

“Pita bread?” The severe waiter looked at him with raised eyebrows.

Last night they had called it Arab bread and he very much wanted the same thing and was unfamiliar with this cuisine and faltered a moment.

“The one that puffs up,” Jack said, doming his right hand over his outstretched left one. “Pan Arabe.”

“Pita,” the waiter confirmed, and reached toward the table.

Jack put two fingers on the menu and looked up at the waiter, who smiled and withdrew with a flurry.

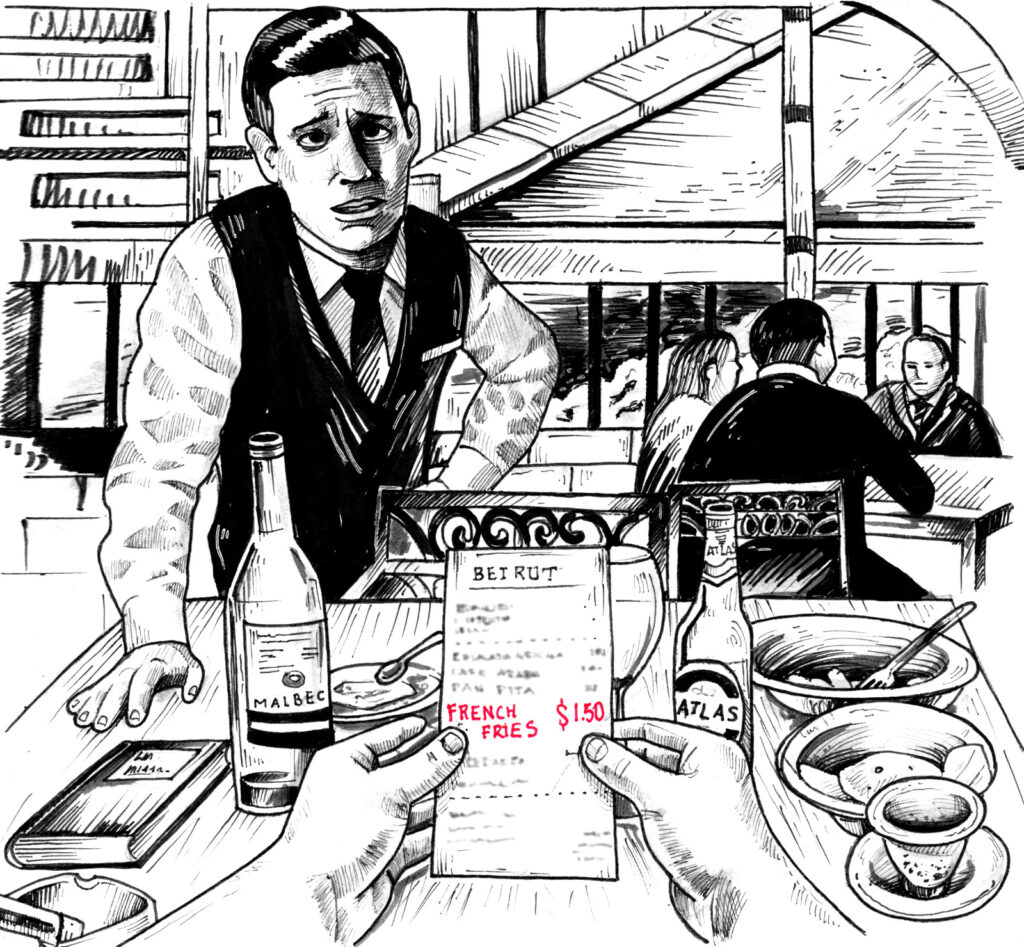

The first night they had made an error on the bill. He had ordered Greek salad, Pita bread, one wine, one beer, baklava, and Arab coffee, but like a fart in a scuba tank, an order of French fries had appeared on the bill tendered after a pleasant stay on the welcoming terrace. The waiter to which he had objected had been understandably apologetic and had it stricken at once. Jack had tipped handsomely, irrespective of the service charge added to the bill. Last night the bill had been perfectly in order, so he knew that it had just been a mistake.

Jack Stone let the book rest and ignored the cigar and enjoyed the cosmopolitan delight of pleasantly sipping his very cold beer in a clean, well-lighted place and was disappointed by the speed with which his order arrived but appraised the salad favorably and moved it around with his fork to distribute the feta. The bread was sunken a bit and sat there on the plate, not fully inflated like before, no steam rising, but what the heck. The dressing was the same, only there was less of it this time. But the olives—Kalamati the two nights previous—were just plain pitted black olives tonight. Still it was very good, not transcendental perhaps, but good enough. He tore a piece from the pita and knew from the touch that it was not the same, and his palate recoiled ever so slightly in its begrudged confirmation. It was neither soft and hot nor hard and cold but somewhere in between. But the night bewitched, and the bread would soak up the dressing and feta crumbles left at the bottom of his bowl, and it was all good.

He ate slowly to hold the moment but eventually he was finished and the plates whisked away. The hunger was gone now, and he might have called for the bill and stepped out into the night, but the tranquility and satisfaction of his utter solitude was too intoxicating, and he resumed reading and worked at his cigar a while and drank his beer slowly to preserve the moment. A quarter hour later he canvassed the menu and zeroed in on the appetizer platters that featured a bunch of different things, amongst which the dishes that he recognized included pita, hummus, and baba ganoush. He had never had baba ganoush but knew it to be an eggplant thing. He was ambivalent about hummus, neither liking nor disliking it, but the presence of hummus itself on all the combination platters was by no means a disqualifier.

“The Tripoli platter is the most complete,” the bored swarthy waiter advised. So the Tripoli platter it was. “And another beer?” Why not?

It was the part of the book where the hero was cast into the gutter by a society that feared him for his greatness, and the love interest rebelled against that society by marrying the hero’s arch-rival whom she despised. It was a fictional world quite unlike Jack’s real one but with an intact logic and compelling action, and he read with angry and sanctimonious delight the perfidy that would take hundreds of wonderful pages to set right.

The food arrived on the arms of two waiters and comprised seven separate dishes in small bowls and another pita on a plate, this one fully inflated though still not steaming. A fresh clean plate was placed before him, he was bid buen provecho, and Jack Stone stared at the culinary constellation and took a chastened drink of beer, perplexed as to what it all was and where and how, exactly, to begin.

He deduced correctly that the white stuff was the yogurt-cucumber thing that his Greek college buddy had called tzatziki. He inaugurated with a piece of pita ladled with hummus to discover that his ambivalence toward the garbanzo dish had apparently not matured, and he turned to the fried rice that had long crispy things that looked like squid tentacles but turned out to be fried onions, and on a little mound that he made of the rice he spooned baba ganoush and tried it. It did not knock his socks off but did not need to be sent back, and he dolloped on tzatziki and found the next bite better. He tried it next with hummus, but that was still not working for him, so he got a spoonful from the bowl of puree-ed stuff, the identity of which he could not discern, and spooned up a small bite to try on for size. Beyond the little drizzle of olive oil on its surface, its ingredients remained a mystery to him, but its defining quality, he decided, was its insipid similarity to the hummus, and he returned to the eggplant, this time heaping it on a piece of pita and strained his palate for a marvel that remained elusive.

He sighed and gazed upon the two untouched dishes, in which he expected to at last encounter a bit of meat. He had saved these on the periphery where the waiters had placed them, and as he had a drink of beer and surveyed his progress was reminded of the myriad small cups all those years ago of invariably slimy bizarre unidentifiable things that he had come to conclude was the hallmark of Korean cuisine. Only then he had been couriered around by solicitous Korean patrons, then handmaidens to his corporate American overlords of that bygone era of his life. One of the remaining dishes was clearly a Lebanese taco, fried crispy, and he took a bite, rewarded with savory tidbits of an unfamiliar meat that he presumed was lamb, but suffused in spices through which the predominant note was that of cumin. It was even better with tzatziki, and he set it down after the second bite to pick up the fried brown dumpling-like thing that had the perfect form of a pregnant jumbo jalapeño pepper, or perhaps an oversized pejiballe palm fruit. It was still warm to the touch, the breading deep brown, and his bite released a gratifying taste of mint and other herbs sufficiently well balanced that none other stood out amidst finely ground fried beef. This one went well also with tzatziki, and he ate it all and polished off the remaining half of the taco thing and found the intrigue worn off but finished the eggplant and mopped the remains of the yogurt with pita and pushed the unfinished hummus and quasi-hummus away to glance at a waiter, eager now to close this chapter and get back to the hotel to study the schematics with which he had to be well-versed at tomorrow’s meeting.

He looked over the bill and glanced up at the nearest waiter, a young woman, who hurried over to him.

“There are two pita breads on the bill,” he looked up querulously.

“Did you not have two?” she replied brightly.

“Yes, but I thought the second one was included in the Tripoli platter.”

She screwed her forehead into furrows and studied the bill that he showed her.

“I remember seeing it on the menu that it was included,” he explained. “I certainly did not order it separately.”

“Let me see,” she hurried away with the bill. She returned a few minutes later with a new bill and deposited it before him in the handsome leather tip binder, smiled faintly, and scurried away.

The final waiter, the one that brought his change, was boyish, handsome, and very slim, not yet a full man but well beyond a boy, and unlike the others, wore an enormous smile and worked his dark gentle eyes into innocent pools of empathic benevolence.

Jack felt low and mean for not leaving an additional tip, but he was tired of the racket they played here. As pleasant as the place was to sit, and as much as he had enjoyed the three consecutive nights reading and dining, the petty larceny reserved for those like Jack that had been pegged as rich tourists was not just fraudulent, but cheap and demeaning. A two-dollar plate of French fries one night, a dollar-fifty pita bread another night. Perhaps over a full night and the many patrons they raked in a couple hundred unearned balboas to split between management and wait staff. So long as they restricted it to those passing through and not regular clientele or locals, what was the real risk?

On the street his good mood failed to return, the pleasant breeze now sticky and oppressive, and he walked a half block to an intersection to hail a cab. One stopped for a woman thirty meters further along, but as Jack had learned drivers here were wont to do, turned her down after a few brief words and pantomime through an open window, and the cab raced up to stop alongside Jack, who leaned over to look inside. Over the sound of an evangelical preacher on the radio, the driver acknowledged Jack’s destination and waved him into the passenger’s seat, and Jack wondered if the woman had not been declined in favor of his sudden milk-fed appearance on the sidewalk. But drivers did it all the time here and had done it to him several times even, so he did not dwell on it.

The Panamanian character is deadly serious beside that of his easy-going Costa Rican neighbor. But the cabbies here, Jack had found, were particularly dour. It had put him off at first, until he figured it out and found himself in Rome. He had grown an ironic liking to the generic cabbie character. It delivered him from chitchat that elsewhere he might be forced to endure.

But this driver was different. He changed the radio to a station that played foreign pop music and turned to smile at Jack through a thick black mustache, jovial cheeks, lusty lips, and sober eyes that twinkled with mischief. An icon dangled from a plastic rosary from the rear-view mirror. He waved his fingers ‘no’ at a Panamanian couple that stepped forward to ride collective as he paused to pull into traffic and turned to his new friend in not too-badly tortured English as he shot into the night.

“Beautiful night for beautiful city, no?” He looked over with expectant raised eyebrows, and Jack obliged him.

“Indeed,” he replied. “It is a beautiful night for a beautiful city.”

The ride would be a short one, and the driver’s friendliness was so frank that Jack acquiesced good-naturedly. It was not his country, and he owed its people whatever graciousness he might muster, and there was no light by which to read or feign reading, so he went with it.

“I take you to a night club where they have the best girls,” the driver suggested. “Very young girls, freshly arrived from the country-side.”

Jack laughed.

“Yes?”

“The hotel will be just fine.”

“But,” the driver pointed to a night club as they passed one, “that one okay but not the best. I take you to the very best one. You will see that you will have great fun!”

Jack looked over and switched to Spanish. “I just don’t care for that sort of thing, is all.”

“You speak Spanish very well,” the driver adjusted his tone in his own language. He pointed to another that they passed.

“Perhaps you should check it out,” he urged with lesser insistency. “Better than your hotel this early in the evening . . . “

“I really don’t like that sort of thing,” Jack repeated.

“What sort of thing do you like?”

Jack held the book up to the driver. “Literature.”

“Ah,” the driver replied. “I see. We Panamanians read very little. Just the newspaper sometimes, but these days we watch the news on the television. Every Panamanian has a television. Very little reading in Panama. It is one of our great faults.”

“Well,” Jack mused. “I don’t know about that . . .”

“I have an American friend,” the driver changed the subject. “He too does not like the girls. ‘Cocaine,’ he says to me, turning again to English. ‘Cocaine is all I want. No girls. Only cocaine. Cocaine, cocaine, cocaine.’”

“I’m sure you are a great help to him,” Jack replied in English.

“So you want I help you out as well,” the driver pounced, back in Spanish.

“I don’t particularly care for that sort of thing,” Jack replied dully.

They rode in silence for a few blocks and approached the left turn onto Via España.

“There is a great church that I would like to take you to,” the driver offered, settling finally on Jack’s fetish.

“Sorry. I’m an atheist.”

“Ohhhh . . .” the driver replied, his foot lifting unbidden from the accelerator. “In Panama there are no atheists. There are some, very few, who perhaps do not believe in God. But there are no atheists.”

“Well,” Jack mused. “I am not so sure about that . . .”

“In fact,” the driver burst into laughter, his right foot recovering its muscle memory, “if you tell that to just any taxi driver, he is certain to stop the car and push you into the street, even in a bad neighborhood.”

“You may stop the car,” Jack smiled, “and push me into the street if you wish. The hotel is near now; I can walk the rest of the way.”

The driver laughed uproariously. “No, no, no, my dear friend, you misunderstand! Not me! I would never do such a thing. It is others. I mean it only as friendly advice for the future.”

“Well thank you,” Jack smiled. “I will remember your advice.”

They were now a block away, and the driver gestured toward Jack. “What is the literature that you are reading,” he asked, his tone now brimming with innocent curiosity. “I cannot read the title in the darkness.”

Jack lifted the book to show the driver the cover. “It’s called The Fountainhead. It is written by a Russian-born author—a woman—whose name is Ayn Rand.” The cab pulled beneath the hotel awning.

The fare, Jack knew, was two dollars. He stepped from the car. He was in the habit of paying with a five and leaving the change as tip. This was, after all, not his country and he preferred to err as needed on the side of generosity. Besides, it seemed like a fair reward for the typically gruff silence that allowed him to inhabit his own thoughts in peace. He half smiled at the grinning cabbie. “How much do I owe you?”

The moment’s hesitation was more pleasant than and as illuminating as even one of the author’s very good metaphors.

“Three balboas, Sir,” replied the grinning driver.

Jack fished out three coins.

“And this is your favorite author of literature?” the driver asked, taking the coins.

“No.”

“So? Who then?”

“Fyodor Dostoevsky is my favorite author of literature.”

“A Polish author of literature?”

“No,” I replied before turning away. “Just another Russian.”