Descanse en Pedazos

Rest in Pieces

PD Collar

Art: Inara Padilla Salas

The machete that ended Pancho Coto’s life had barely stopped quivering before the news began to spread. As blood oozed from around the steel buried in his neck and Pancho’s eyes began to lose focus, his breaths to lengthen, a witness hurried up the side of the hill to get a bar and called his cousins and some pals, and before long, the Guardia was in the know. The station-house buzzed with the news, and the night shift emerged grumpy from the bunkhouse, awakened by the energy in the air, to see what was up. The news was a barrel that rolled up Main Street spilling its juicy elixir from both ends before ballooning into a giant tropical snowball that shook the town like a temblor in its swelling passage. It was a cloud that blanketed the village in an electromagnetic maze of texts, calls, Facebook posts, and WhatsApp messages.

In the minutes that it took for the intelligence to settle upon the town like a blow from across the Gulf, the news was known as far afield as Kodiak, Dusseldorf, and Brisbane, and had conflated the events to a massacre of a dozen men by Maras in body armor and tactical vests, their faces inked and ferocious. In the quickened marrow of innuendo, drugs were presumed to figure into the case; probably betrayal of hard-working simple people by certain self-anointed standard-bearers of civic probity, certainly corruption among institutional bodies, and of course, at the base of this tapestry of suspicion and rumor the whole affair was rooted in the primal savagery of the forest itself. Within an hour, however, confirmations from the field revealed that it was just one man killed, none other than the town’s notorious Jupa de Soncho, and that he’d been killed in a fair fight by a decent man protecting his home.

Not long after dark, fireworks were set off in the Urba, echoed by bottle rockets and cañones from the harbor front, and even Pueblo Viejo got into the act. By eight in the evening, a procession of freshly washed cars took to the streets with pretty girls waving from the backs of pickup trucks and horns blaring that wound itself through town three times to celebrate the news before devolving into a raucous and bacchanalian euphoria. Bosses widely canceled work for the next day, and in the Coloreteada Bar, free guaro was dispensed for a full fifteen minutes. The police even condoned dancing without a permit for the night. The spate of festivity rivaled the solstice fiestas of San Juan, and nine months later a bevy of babies celebrated belatedly in the act of being born.

*

The barrel rolled right past the downtown entrance to the Bar China, inside of which Ivana Santábria drew a moist rag across a timeworn counter in the acid hours of late afternoon. Hairs rose on the back of her neck at it rumbling passage, but she shrugged her shudder to lingering nervousness at the new job, butterflies over all the unwelcome attention she drew as the new girl.

At thirty-eight, she still had her looks and the right balance of curves and maturity to primp around in a tight mini and low-cut top to sling drinks and beers to the boys without being overrun by them. The cheap beer and late-night hours made for a rough, male crowd, and there was an exudate of testosterone on the walls and condensate on the ceiling that melded into a waxy film that covered all the surfaces of everything she was required to touch, oily-like, to boost the joint’s cachet sleaze among the strata of society that could afford better.

But its pedestrian traffic was the working young, lottery vendors, street hustlers, nickel-bag coke dealers, the itinerant homeless flush with fleeting coin, hookers, and the hard ranch hands and wiry gold miners in from their ranches and claims for the weekends, plus the odd out-of-town thug laying low from police or judicial notoriety elsewhere that always stood out and spawned hushed murmurs as to the degree of his desperation or meanness. Ivana smoothed her skirt in the empty pregnancy of the breezy cool before dusk and ran her rag across the glass rings left by an aging trollop that had waddled out to follow the rolling barrel .

It was, frankly speaking, only one step above hooking, a trade to which she had never reduced herself in the struggle to get ahead, or lately to just get by. Mario’s death had been a cruel blow. After eight years together and happy, she had been right on the verge of decent middle-class living as the common-law wife of the town’s hard-working butcher, a self-made and respected merchant. But national healthcare was insufficient for the cancer that was diagnosed, and they had gone through his savings for private medicines and treatments, all in vain. She took over the butcher shop when he was no longer able to work, but even with Nando’s help she was no match for the BM supermarket that had opened a year earlier that bore down on all the small businesses, leading not just the butcher shop, but also the greengrocer, the bakery, and fruit stand, to fold, one by one. She had wiped out a salted-away nest egg of two million colones to settle final accounts with vendors, Social Security, and back rent, and stored the meat grinder, cold-locker, saws, scales, cleavers, knives, and meat hooks in the bodega out back less than one month after setting up Mario with a crypt finished in ceramic tile and leading his final procession for which enough of the town had turned out to burnish her ambition to move on and up. But the bills kept coming, and with the money gone, and the girls growing and school uniforms and books and all the other stuff of life and Nando struggling to make his guiding pay regularly, she had jumped when Pirulo came to her to suggest she shimmy into something tight to come tend bar for him here at the China.

“Another águila, Don Bartolo?” she offered.

“No, gotta run,” he replied, fishing out a rojo to lay on the counter and slipping his phone into his shirt pocket. “And go see who they’ve killed now.”

She genuflected as he rushed out and noticed the three drunks gathering on the sidewalk to look in at her and talk among themselves. It was a minor conspiracy into which they sought to draw her through knowing looks, and she grew uncomfortable. She withdrew to the back to order the counters there and to fetch ice as an afterthought and emerged to find the sidewalk had grown crowded with people now looking in at her, not a soul at the bar itself. Pirulo screeched to a halt in his fancy truck and before he could get the door open, Juana Sánchez came running from down the street and rounded the corner into the doorway and straight to the swinging bar counter to duck beneath and breathing heavily, seize Ivana by her arms to emote her despair.

“What is it, girlfriend?” Ivana put her hands on her Juana’s hips to settle her down.

“They’ve killed him, Vani,” she managed, water welling in her eyes.

Fernando flashed through her head, a comet streaking through her solar system. “Who?” she declaimed. “Who have they killed? Who have they killed now?!”

“Your husband.”

“My what? Mario has been in the ground for two months; what kind of a thing is that to say?”

“No,” Juana pleaded, convulsing now. “The other one. Pancho Coto, dear . . . they have killed him with machete blows in the Tigre.”

Across the counter Pirulo looked on with his cowboy hat in hands, his features awkwardly softened from his gold-miner roots and contemporary crime-boss gruffness into a semblance of empathy.

“Get your things,” he told her softly. “Marjorie is on her way to take over. I’m taking you home.”

“No,” Ivannia insisted. “I need the money; this is my job! That man meant nothing to me . . . !”

“He was once your husband,” Pirulo replied. “It wouldn’t be proper for you to remain here. I will pay you for the time, don’t worry; go get your things and let’s go.”

*

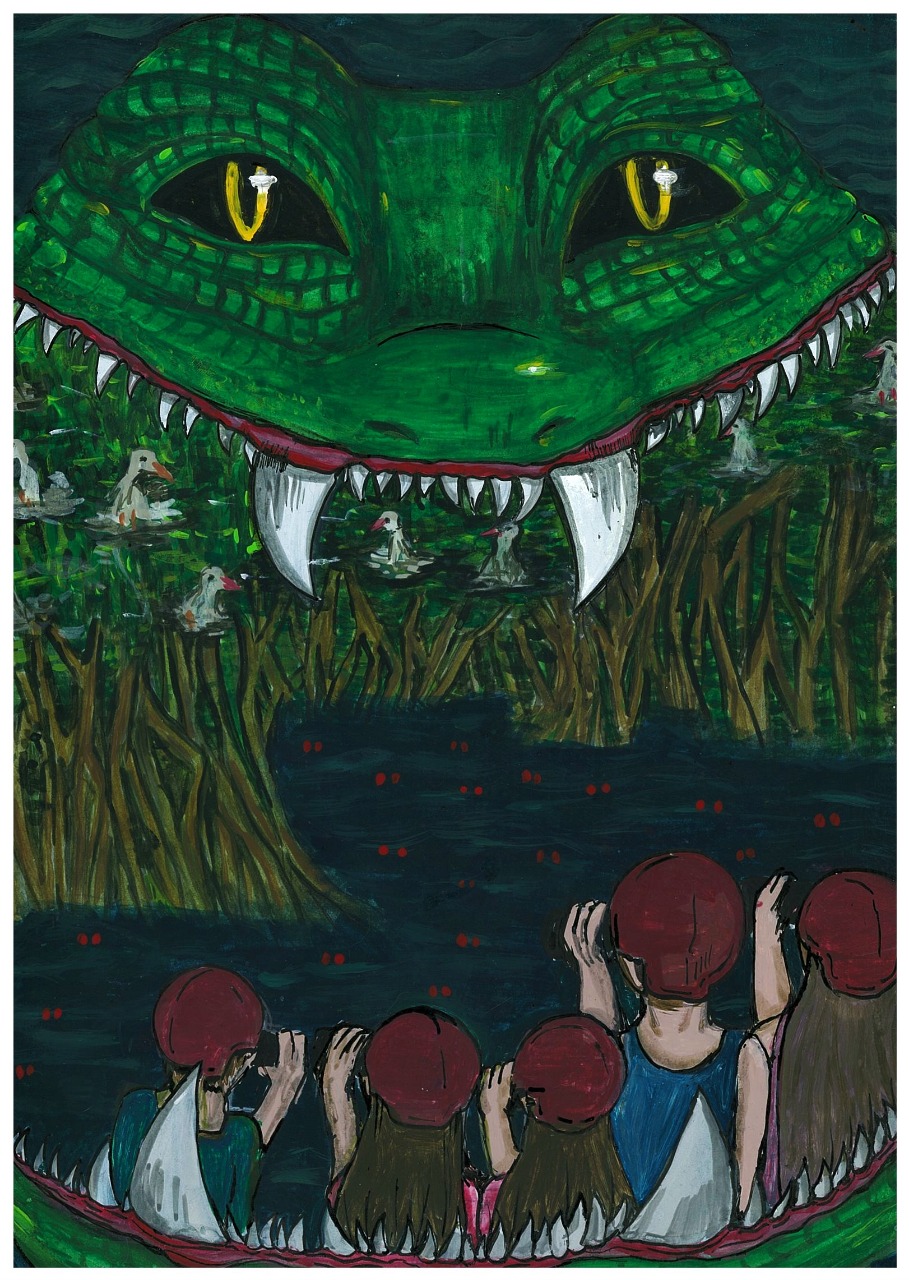

The news that raced around the known universe of the Osa Peninsula failed to penetrate the darkening tones inside the mangrove swamp on the edge of town only because the two guides trundling tourists into the forbidding brambles had their cell phones turned off. Fernando Santábria huddled with his Dutch couple at the water’s edge beyond the rookery, encouraged that his nemesis, Jose Artávia, was nowhere to be seen, giving him that night’s run of the swamp. The two guides had divided the terrain equitably, with cleared landings on opposite ends of the rookery in the middle of the water, and each guide tended his own landing as needed with discreet afternoon ventures into the swamp with hidden machetes to trim the woody growth to give their tourists a place to stand comfortably and not be crowded by the woody tangle and to keep the trail passable–tight and disorienting—but not overly claustrophobic. At night, to the uninitiated, the living vegetation, the insects, spider webs, the idea of snakes, drops of water, gusts of wind, and the eerie calls of the juvenile ibis all made of the swamp a cauldron of primal savagery, a forbidding, scary place. Nando surveyed the still dark water for reptiles as his clients took it all in.

“The ibis, they like the lower parts of the mangrove, closer to the water.” He pointed out the mangrove tree rising from the middle of the lagoon, its branches and foliage spread like a banyan across the still, black surface. “You see that at this moment there are only a few of the cattle egret in the upper branches,” he enunciated in the language he had learned as sport fishing deckhand and hustling tourism in town. “But soon,” he looked into the greying sky, “the whole flock will return to cover the top branches where they will roost for the night and then fly away again as the light first appears from across the gulf.”

“Is it typical for dese distinct baird specie to groost togedder,” the man asked. “Do dey chair some symbiosic grelation vit von anodder?”

“No, in this case, it is just convenience,” Nando replied eagerly. “In fact,” he chuckled, “I think they do not like each other very much, like neighbors in general, but they are safe over the water together, and so they make the allowance that they must in order to sleep well at night and rear their young.”

“Interestink,” the man allowed.

“Sometimes the baby ibis, he gets too eager,” Nando reeled out his shtick, “and he leave the nest too early, before he is ready, and he fall in the water, and then . . . “ He brought his hands together from a hinge he made of the butt of his palms to simulate the jaws waiting in the water below. “Chomp!”

“How awful,” the woman shuddered. “Such a terrifyink fate for an innocent hatchlink!”

“See there,” Nando pointed to a small protuberance in the water: “is a caiman.” As the clients tried to form in their mind’s eye the head of a caiman from what appeared to be mere flotsam, another surfaced next to the first, and it was clear that it was true, and now there were two. But they were hard to see. Knowing what they were thinking, Nando explained. “In a few more minutes with a bit more dark, we can see many red eyes in the water, with the head lamp.”

The man tried his, but it was still too light.

“Perhaps with my treats, we will be able to coax El Gordo from the depths,” he smiled. He doffed his day pack to retrieve the package of fish remains that he had bought at the Marisquería Corcovado. Sometimes he could get the remains for free from fishermen, but at the restaurant they always claimed that the heads and spines left from fileting the fish was valuable for soup stock and that he must pay them for these remains; even when they had too many to make them into stock, they still charged him. Still, fish remains were cheaper than chicken guts, heaven forbid the costly entrails of pork and beef, which the reptiles most favored. He opened the plastic bag and tossed one of the fish spines into the water to wait for more darkness to surround them, and as his clients focused on the floating fish head, Nando spied his rival down the way with four tourists. He quelled the unsettled feeling of the sudden competition. José was the son of a pig farmer, and he was never short of the pig guts with which Nando’s miserable fish spines could not compete. It was unfair of course, like life, and you could not even make soup stock from pig guts . . . Nando saw a vee in the water from the corner of his eye and turned his clients’ attention toward it and flicked on his head lamp. “You see,” he pointed at the approaching pair of red dots. “A caiman is making his way to the bait.” The tourists fumbled for their cameras.

Sure enough, the reptile zeroed in and roiled the water to disappear into the murky depths with its morsel. The magical part of dusk enveloped them, and tiny red pairs of eyeballs popped up through the light from each of their headlamps as the beams roamed across the dark surface and the air swelled with the calls of parrots flocking to their roosts in the Platanares swamp to the north. There were easily a hundred sets of eyes out there.

“Dey seem to be svimmink avay fum oss,” the man complained.

“Look, here come another caiman.” Nando pointed out a juvenile that made a nice swirl as it took the bait. The clients were slow to react, and by the time they snapped the pictures all that remained on the screen was a glare of the flash immersed in gloom and a suggestion of the wake on the otherwise still water.

As splashing sounds and shrieks of glee drifted across the swamp, the man announced: “Dese caimans are very interestink, but ve vish to view the Crocodylus acutus!”

Nando threw more fish remains into the water a short distance from where they stood and mentally genuflected to the reptilian pantheon to send its greatest emissary, El Gordo, more mythic and noble than the Dutchman’s submissive cousin. El Gordo was a sea croc, enormous, self-possessed, and with a great sense of humor. He was fond of the two guides, Nando was sure, and played them off one another. But after a few minutes, his bait remained unclaimed, reposed impotently on the still surface as the animals swam toward Jose’s perch, where the noise was testimony to his competitor’s greater success in luring the reptiles to his Canadians. Before it was too late, Nando urged his clients back from the bank and onto the trail. “They seem to favor the other end of the swamp tonight, let us go there to see better.”

José was gracious but smug in welcoming Nando’s clients to their group. In the water there was a froth of furious thrashing as two crocodiles checked each other for positional advantage for each newly tossed morsel, the caimans crowding the edges to dart for remains that escaped the dominant snouts, all the animals whipped to medullaic frenzy. Through his requisite smile and impeccable manners, Nando evinced pleasure, consoling himself with the happy talking between his clients and José’s clients, all wide-eyed, and like paparazzi with their cameras. Nando would have to pay José $10 apiece for joining Jose’s group like this, leaving only $30 total for the evening’s work, rather than the $50 he had mentally allocated to the overdue electric bill. Still, it was better to sacrifice a bit than to disappoint clients. From experience he knew it was simply not in the nature of Dutch people to give tips. They were like Ticos in this way. But Canadian, Italian, French, and other nationalities, they all tipped, though Americans proved the most generous in this regard. He smiled at the show, despairing at being beat out again, all because of José’s market advantage with free high-quality bait. It had been very difficult since his step-father had taken ill. But with his death the shoes to fill swallowed yet his feet.

As Nando troubled over the economic math, the activity in the water stilled, and Jose’s arm shot out to the middle of the lagoon where a pair of red eyes about thirty centimeters apart moved slowly toward them and the throng of smaller reptiles edged away. “El Gordo,” José announced, completing Nando’s defeat at the rear of José’s landing. Sure enough, it was El Gordo, all five-plus meters of bristling sea crocodile, sinew, muscle, claw, and tooth, gliding sleekly through the still water, the lesser reptiles edging away, none willing to contest the feed zone. José had pig liver quartered and saved for the occasion and now fed the animal slowly, piece by piece. The monster chomped delightedly and swam right up to the edge of the water to look up and smile at the ashen tourists, who stepped back to gape. Dutifully, the beast opened his jaw wide to share with them the massive pink innards of his awesome maw ringed by giant ugly teeth. The tourists took another step back, gasping at the display, and one of the Canadians tripped on a root and fell over backward and yelped in panic. Those that retained their footing struggled to still their hands to make their cameras operate. After several pregnant moments, the scene lighted with many flashes off in rapid succession, and the photography went on for a full minute. Nonplussed by the lip-smacking pheromones of the trembling group and signals of weakness and vulnerability, El Gordo held his fearsome pose to let everybody get a good shot, and José tossed him the final treat—the very heart of the pig. El Gordo closed his mouth slowly and chomped and mashed in an epic evocation of delight; he looked up directly into José’s eyes. The animal seemed to wink just before easing back from the bank to drop beneath the oily surface.

“We must back up,” Jose extended his arms to protect the group and stepped theatrically backwards. “At this point sometimes he lurches from the water to attack.”

Nando rolled his eyes but locked away the showmanship trick for future reference. The six tourists did not require more inducement and scrambled back away as the sky came alive with the raucous onslaught of the ghostly egrets converging on the roost and the plaintive reply of the ibises reposed in the lower boughs, and Nando figured that Jose could surely drink beer at Juanita’s till closing on tonight’s tips alone . . .

*

The police pulled up to the Santábria home in Pueblo Viejo at nine the next morning with their awkward package.

“What?” Ivana screamed in outrage. “And what is it that you expect from ME? What am I to do with him?”

The Lieutenant was unhappy with his orders and had refused to delegate the assignment to subordinates. Doña Ivana had her share of struggles, and it was unfair; she had recently lost her main husband and was apparently reduced through her circumstances to tending bar at one of the cantinas like some sort of slattern. But the lieutenant was from San Vito, not the Osa, and he had not the local network to sort this out with the town elders, who had seemed to shrug their shoulders and turn their backs to it.

“You are his next of kin,” he explained. They are your remains to dispose as you see fit.”

“That’s what the morgue is for in Alajuela,” she retorted. “Send him there!”

“There is no call for forensic investigation; it is clear how this man was killed.”

“I call for a forensic investigation,” she declared severely, Nando bristling shirtless by her side, her three daughters crowding the doorway to take in the scene, the little one sucking her thumb.

“Doña Ivana, I am sorry, but it is too late for that. This is a decision over which I have no control. And it has been made, and this is the way it is going to be. I am sorry.”

The officers opened the tailgate and slid a piece of plywood that was left over from the station remodel upon which the corpse was reposed, wrapped in a white sheet stained heavily in the torso and head region with ugly brown crusts. They deposited the ghoulish ornament in the well-tended lawn between the hibiscus hedge and the concrete walkway to the front porch. Then they piled into the truck and headed back to town. Before the dust from their abrupt April departure had even begun to settle, Ivana looked down to see that flies gathered at the folds of the sheet and crawled in and out, buzzing. There was a bit of smell, not yet overpowering, but still, the clock was now clearly ticking . . .

*

After she and Nando dragged the litter to the back yard and out of the public eye in the shade of the bodega, Ivana showered vigorously and marched herself into town on a beeline for Fausto Justino’s house, where she found the head of the Cemetery Committee rocking on his porch, expecting her. She declined his offer of lemonade.

“One million colones?” she gasped softly. “For Mario it is one hundred thousand but for this one it is TEN TIMES MORE?”

“Doña Ivana, I am sorry, but in order to isolate his remains in a manner befitting the dignity of the town’s deceased, we must buy the adjoining lot, the empty one on the north side . . . “

“What?”

“It’s three million they are asking for the lot, and we are prepared to put two thirds of the money up, so all we need for you is one little million to close the deal.”

“One little million, Don Fausto?”

“That’s all it will take, and we can get this taken care of.”

“It’s a cemetery, not a housing project.”

“Perhaps, Doña Ivana, but the dead are not all the same, and the committee must consider community objections to the proximity of the remains of your husband to those of their passed loved ones.”

“He’s NOT my husband!”

“Well,” the dignitary deflected patiently beneath her withering affront. “What is he then, Doña Ivana? He has no mother, no father, no siblings, no children that claim him. You are his next of kin, and he is your responsibility.”

“This is not right, Don Fausto. Help me.”

“This is the way it is done, Doña Ivana. What other way is there?”

*

By late afternoon, the corpse of Nando’s mother’s first husband had begun to ripen, and the smell now pervaded most of the back yard. The buzz of flies in the full celebration of decaying flesh could be heard from the back door. Left to watch the house while his mother made arrangements in town, Nando worried over the time it was taking and the deteriorating conditions at home and sized up the challenge to take a stand. He moved the items in storage around to expose the meat locker and called Pepito over to help him. Pepito was an electrician’s assistant and able to borrow some cable from his boss, and they rigged an extension cord that Pepito wired into a 220V circuit breaker that was unused since they had sold the air conditioner last month to pay last month’s mortgage. It had kept Mario comfortable in his final days, a luxury not even then within their means. Pepito offered to help him with the rest, but Nando would not hear of it; he would take care of the dirty work personally. “Just loan me your tape measure,” he said.

“You mustn’t observe,” he admonished his sisters, insisting that they watch the television instead and stay in the house as he studied how to go about the fit. The meat locker now hummed and grew cold. He dragged the corpse by its feet off the plywood and into the bodega door and laid it out on the dusty floor. He measured the object and container and studied the cold-storage challenge of supply and demand. When it was clear that there was no easy fit, he wrestled with the corpse, but struggle as he might, he could not get the legs to bend at the knees. The corpse simply refused. Even breaking the leg bones, Nando reasoned that it was the flesh itself that had grown firm. Outside of cutting the legs off, he could see no manner of getting the body into the icebox. Nando was not yet prepared to cut the legs off this or any man, dead or otherwise, and he fled the body and its oppressive stench and attendant phalanx of flies to the embrace of the shower to retrench and re-think the options.

*

“What about for medical research?” Pirulo asked, the air conditioner lively in the cab of his fancy new truck. It was after eight, and Ivana had been pounding the streets all day, trying to figure out a way.

“Only within 24 hours of death or unless preserved with embalming fluid or. . . that’s what they said.”

“And no landowners will give you a patch of ground somewhere for you to take him to? I will help you bury him.”

“No one will take him,” she looked down through swollen eyes. “I have asked everyone.”

“So you must cremate him, then.”

“How will I afford the wood? And what will the neighbors think?”

“There are crematoria, Ivana. There is surely an institution for this.”

“That’s five hundred thousand, Don Pirulo, and I still have to transport him all the way to Chepe for this cremation. It is illegal to transport a dead body; how am I to find and pay for someone to haul this corpse to San Jose? It would probably be cheaper to pay the million I don’t have and can’t borrow to bury him here.”

But a million wouldn’t do it, and Pirulo knew that the town was not having any part of Jupa de Soncho’s burial, and that the million had been tossed out as more than she could possibly afford, and if she came up with it, they’d tell her two million or five or finally just level with her that no amount could ever pay his way into the grave yard.

She looked up with the new resolution of the fallback. “I will have to pay a boat and bury this man at sea. There seems to be no other way.” She leaned across the seat and kissed his cheek and got out of the truck and did not look back as she crossed the yard and gone inside.

*

It was too late to be calling the town’s boat fleet. They all slept early to rise well before dawn, but there was no standing on ceremony at this point. A quick canvassing revealed a general reticence to get involved.

“This is pretty irregular,” bemoaned Sanchez. “I would risk everything, Doña Ivana to be involved with this . . .Are you sure you want to ask this of me?”

“It’s illegal,” pointed out Patona. “Hell, the whole town is waiting to see what you’ll do . . . “

“I can’t get mixed up in this,” Old Man Ramirez said it straight. “My condolences over your hardships, God keep you strong . . . “

Nando wrapped his arms around his mother as the enormity of her vexation led her no recourse to a flood of tears.

“It’s going to be alright, Mami. In the morning when it is clear and we are fresh, we will solve this.”

She looked into his eyes, and he was right. This was just a passing hardship.

But you must rest this evening, Ma. You must really sleep. You must take one of Mario’s pills and get real rest. The girls and me, we can’t have you worn out from not sleeping. Tomorrow’s too important a day.”

“You are right,” she said and pinched his nose. She dismissed the Mario’s pills idea but found in her son’s footing her own foundation. There was a rational and moral order that would reveal itself through a good night’s sleep. “Let’s all go to bed and face this fresh in the morning!” The girls went to their room without a peep and Nandito brushed his teeth and closed the door to his room, and Ivana decided in the sudden calm that she really did need a good night’s sleep and took one of those pills, after all.

*

“Upe. Upe…”

Ivana awakened to Juana’s call to discover from the light in the room that the morning was well advanced, and she leapt from the bed and scrambled into a housedress and saw that it was nearing ten. Brushing cobwebs she saw the girl’s door open and them presumably off to school. Nando’s door was atypically closed, but she dismissed it with Juany at the door and ushered her in.

“Thank heavens you came by,” she proclaimed. “I took one of Mario’s pills last night, and who knows how late I might have slept . . . and so much to do today!” She looked around outside and sniffed the air. “What a beautiful morning,” she said

“Good news,” Juana announced.

“Don’t be shy, sweetie. I could use some good news, though it is a beautiful morning, I have to admit.”

“The squatter Geronimo has agreed to lend us his dugout,” Juana announced vibrantly. “It has no motor, but the water is very deep right off Puntarenitas Point, and we can paddle out and back in and be done with the whole thing in two hours. He will even help for fifteen rojos.”

“That is great news!” Ivana exclaimed. “Why even if I can’t get a truck, it’s only two hundred meters to the beach. I am sure that somebody would lend me a wheelbarrow. . .”

“I asked him to paddle over at once, so he will be waiting within an hour.”

“I have not yet had coffee, dear.”

“If you have not yet had coffee, then let’s go make you some.

They repaired to the kitchen where Ivana put water on to boil while Juana prepared the sock.

“God bless you, Vani, such tribulations,” Juana gushed. “You are an example for all of us. I, for one, just want to help.”

Ivana wrinkled her nose. “This is going to be a pretty stinky job.”

“But after a spurt of unpleasantness, it will be over with, dear, and you can get back to your life.”

“We need a ‘shroud’ of some sort.”

“I brought sacos. I’ve done the math. We can do it with three together, the middle one cut out and sew them together. I have fishing line, and all we need are some good rocks and we shall be set! Where’s Nando? We need him. It is still going to be hard work.”

Ivana bolted her coffee and looked grimly up at her friend. “I must go take stock of the task,” she declared.

“Let’s go,” Juana replied bravely.

“Juani, you have done more for me than I could ever ask. I cannot involve you further in this. I cannot have you troubled with tending to this corpse. I prefer that you allow me to take care of this.”

“Don’t be ridiculous, Vani; now let’s go.”

They looked at one another as Ivana held the knob. “Ready?” she said, wrinkling her nose.

“Ready, sweetie . . . “

But when she pulled the door open, the body was not there. There was a lingering smell, not unlike that of a dead rat hidden away in the walls that eventually went away. It was unpleasant but not overwhelming, a smell manageable with cloro. The body was gone, flesh, blood-caked sheet, plywood plank, all of it: gone.

“But . . .” Ivana objected. “This is not possible.”

“Vani,” Juana blurted. “Don’t you see? They came in the night and hauled him away! They felt remorse at saddling you so unfairly and stole in under cover of darkness to remove the body and bury it somewhere in the mountains!”

The bodega seemed different. The items in storage seemed to have been shifted a bit, though not by much, surely while Nando was trying to discover a way to fit the body in the meat locker as he confessed on the phone to having tried to do. Still, everything seemed to be returned to its original spot but somehow in a more orderly manner. The freshly washed floor had a spot of dampness yet to fully evaporate. “Well,” she frowned, “I suppose that is not impossible, but I cannot imagine them taking the time to clean up afterwards and leave things so nice in here . . . “

“I suspect there was so much guilt over foisting this on you that they took extra care to leave it as if this had never happened,” Juana insisted. “Come, dear, let’s leave the jalousies and door open for this room to air out. Later we can return and give it a good thorough scrubbing with cloro to get rid of the smell.”

It took fifteen paces, from the bodega to the backdoor of her home, for Ivana to discard any doubts or suspicions about anything and to accept the deliverance with open arms, and by the time she stepped inside the house, she was already planning gallo pinto, eggs, and sour cream for breakfast and found Nando wiping the sleep from his eyes and pouring hot water into the sock.

“Nandito,” Juana greeted him with a peck on the cheek and auntly embrace. “You would not believe it; they came in the night and took the body away.”

“No,” Nando replied, not fully awake. “Impossible. Why would they do that?”

“Guilt,” Juana pronounced. “The town saw how wrong it was to saddle your mother like that and in the night they repented and came to make it right.”

“Juany, you must go to the beach and tell Gero we do not need him. I have five thousand here; take it to him; tell him that I will pay him another ten on Friday when I get paid, please be a dear and run me the errand and come right back. And tell him ‘thank you.’”

“Mami, they called me from the tour shop in town, from CafeNet, they have a tour for me tonight. I must be there at eleven to make the arrangements.”

“Nando, are you just now getting up? Is there something wrong?”

“Oh, Mami, it was me that needed to take a pill last night. I tossed and turned and could not sleep for worry. It was not until after daybreak that I think I finally slept a little, but I am still unrested.”

“And you did not hear anybody come in the night?”

“It’s probably the fan, Ma, it makes quite a racket. Also I could not sleep and listened to music on my Samsung with earplugs for a couple hours . . . “ He glanced downward.

“Wait while I make breakfast.”

But Nando bolted his coffee. “Oh no, Mami, I must not be late. This is a family of FIVE Americans, oh Mami, that is $200 for three hours of work. I cannot be late!”

*

In the acid hour before sundown, in the slow part of the day, Ivana busied herself at the bar and managed to make a dent into that awful film, scrubbing and washing, flirting freely with the three clients that drank beer and spoke safely about the upcoming soccer game, rather than personal affairs that were properly none of their business. Unbidden, Juana had made all the rounds and spread the gossip about the good folks in Jimenez deciding to do the right thing to quietly remove the body and bury it in the mountains somewhere in an unmarked grave. Soon, the news was all over town, and many wondered who the generous benefactor was, but that person did not choose to reveal himself, and no intelligence bubbled up about him. The townsfolk deemed it in poor taste to raise the subject with Ivana herself until several months had passed, though many of them smiled at her and greeted her with more friendliness than required, some of them going so far as to congratulate her and to praise the Lord for the good heart of good people. For her part, Ivana was gracious and volunteered nothing and bore only goodwill to all. There was suddenly no lingering nervousness about the job, and she actually looked forward to tonight’s crush around the football game, an opportunity to finally push all the thinking out of her head and be able to simply perform a job for which she was being paid.

*

“That is José Artávia,” Nando explained as he passed by his colleague’s landing on his way to his own. “We are competitors, you see, in this business of showing visitors the swamp.” Nando grinned and winked at the kids. “He has some Israeli clients this evening. Now we will get to see who calls in more reptiles.” The Israelis were with the Spanish in a tipping class below even the Dutch.

Nando roared a bit to Timmy, who roared back a little and laughed. “Crocs don’t roar,” the kid pointed out. “They hiss . . . “

Papa, Nando is going to call these puppies in,” Melissa said. ” I can feel it in my bones, Daddy,” said Elizabeth”

“You see the red mangrove tree and all the ibis in the bottom,” Nando pointed out. “Right now there are only a few cattle egrets in the upper boughs, but at dark a whole flock will return to the roost, you’ll see.”

“Honey, I wish you would get a load of those beaks,” the woman said. “I’ve never seen anything like it in my life!”

“Mighty long peckers,” Dad agreed. “Surely specialized for the ibis niche,” he looked over at their guide.

“It is true,” Nando replied. “They eat crustacean and invertebrate animals in the estuary, sometimes insects and even small fish. They use that beak to dig into the mud for their food. Their young he make a very distinct cry…” An ibis juvenile could not have had better stage presence and spoke up.

“Daddy, that’s spooky,” Elizabeth pronounced. “Like a woman wailing,” Melissa explained.

“It is very similar to the call of the banshee,” Nando explained, “which is a type of chubacabra that I understand is particular to Ireland.”

“There’s no such things as banshees and chupacabras,” Timmy denounced, puffing up. “That’s all a bunch of bohunkuss.”

“You never know, Timmy,” his mother warned.

At his landing he distributed headlights and pointed out the clumps of flotsam beneath the mangrove boughs that were really the heads of caimans scouting a meal. He helped the children to adjust the straps and showed them how to turn them on and off and how to make them strobe. They liked that part. “In a few minutes, with the arrival of a bit more dark, the light will make the animals’ eyes shine red,” he told them.

“Just like the chupacabra,” he told Timmy.

“Ain’t no chupacabras,” Timmy insisted.

“There aren’t any,” Mom said, “ain’t is not a word.”

“It’s in the dictionary mom,” Melissa objected. “It’s listed under the letter ‘A’,” Elizabeth pointed out. The twins looked at each other and giggled as Timmy rolled his eyes.

Down the way, José had already drawn a couple of caimans to his bait, but it was still a few minutes early, and Nando doffed his pack and removed three bags of his own bait.

“Ew!” Timmy observed. “Icky sicky,” the girls agreed in unison.

“Oh this is a special mix of pork and beef,” Nando replied, “aged perfectly for the crocodiles, and I even have a special treat if El Gordo pays us a visit tonight.”

“It’s like stink bait,” Dad pointed out. “You remember what we used last summer for catfish in Grandpa’s pond?”

“Ew,” Timmy remembered, as Nando tossed the first bits of ground meat into the water.

“Stinky winky,” the girls enjoined.

Two caimans raced for the morsel and fought each other in the water right before them, snarling and snapping, something that Nando had never before seen. His clients began gasping and shrieking and struggling to take pictures, and across the way, Nando saw that Jose’s clients were looking his way, José trying to corral their attention back to his little spectacle instead.”

“Spectacled caiman,” Nando pointed out, “caiman Crocodilus,” fully-grown. Equally sized. It’s a fair match.”

“They are mean mothers,” Timmy burst.

“Timothy!” his mom rebuked. The twins giggled.

By the time the light was nearly gone, red pairs of eyes converged upon them, and the two showboats settled into the water to merely snarl at one another as Nando tossed them small treats. In their place four American crocodiles now jockeyed for position as the stink bait flew. The animals lunged and gnashed and put on a fearsome swamp ballet, and the caimans encroached in a covetous semi-circle to edge closer and snap at leavings that strayed beyond the territorial reach of one of the larger animals.

“Oh hello, José, Señor, Señora, meet the Walker family, Mr. and Mrs., Melissa, Elizabeth, and Timmy, you are just in time for a big show,” Nando smiled broadly. “By all means, welcome!”

“Sometimes they prefer to feed at my end,” José explained, “sometimes they prefer to feed at my friend Nando’s end.” Dutifully he stepped back and left the carnival to his rival.

“Look,” Nando pointed out to the middle where a pair of widely-spaced eyes approached from the opening water, all the lesser animals making room. “El Gordo!”

“Mom, look!” Timmy pointed. “It’s El Gordo!”

The girls each grabbed one of their father’s hands and eased him back away from the bank. “Daddy, I’m scared,” Elizabeth said. “Papa, let’s go back,” insisted Melissa.

“Sissies.” Timmy stepped up to the water. Mom pulled him back and held him against her.

The crocodile gentled up to the bank and opened his mouth a quarter of the way, and Nando stepped right up to him and gently laid a morsel of ground meat inside the animal’s mouth and reached around to stroke the beast between its sentient eyes. The animal slowly closed its mouth and began to chew as Nando petted its forehead. The Israelis began to speak to one another in their language.

“Meet ‘El Gordo,’” Nando looked up. “Crocodylus porosus. Salt-water crocodile. Four point eight meters in length. Compressive jaw strength of five thousand pounds per square inch, nearly ten times more than a pit bull terrier…“ El Gordo hissed sharply, and Nando tossed a new morsel into its obliging mouth. Second only to man in the swamp’s food chain.”

“I told you fuckers they hiss!” chortled Timmy.

“Timothy Randall Walker!” Mom objected. The girls giggled.

El Gordo took it all in stride and ate slowly and swallowed and opened his mouth again, and Nando fished out the remainder of the ground meat and illuminated in a surreal sea of irregular flashes fed the reptile what was left of the ground meat, Mom struggling to hold Timmy back from joining the guide next to the beast.

The giant reptile smiled and made a foot feint toward the bank that sent the whole crowd stumbling backward, and the prehistoric lizard moved it head up and down and seemed to chuckle and then opened its mouth wide and held that pose, eyeing Nando expectantly.

“He wants his treat,” Nando observed. The reptile made short work of the slices of liver prepared for him. “Beef liver, one of his favorite,” Nando explained. When that was gone, he removed the final delicacy. “But what he really likes best is pig heart,” he declared, smiling at Jose as he looked back and tossed the organ into the animal’s expectant mouth. Dutifully, the beast gnashed and gnawed and finally gulped the bite down and looked up to give Nando a wink before bowing back out beneath the oily surface of the water.

The sky exploded with egrets coming home to roost as the caimans converged into the void, and Nando extended his arms behind him and backed the group away from the water’s edge, lest the great beast might now lunge at them.