El primer venado de Joey

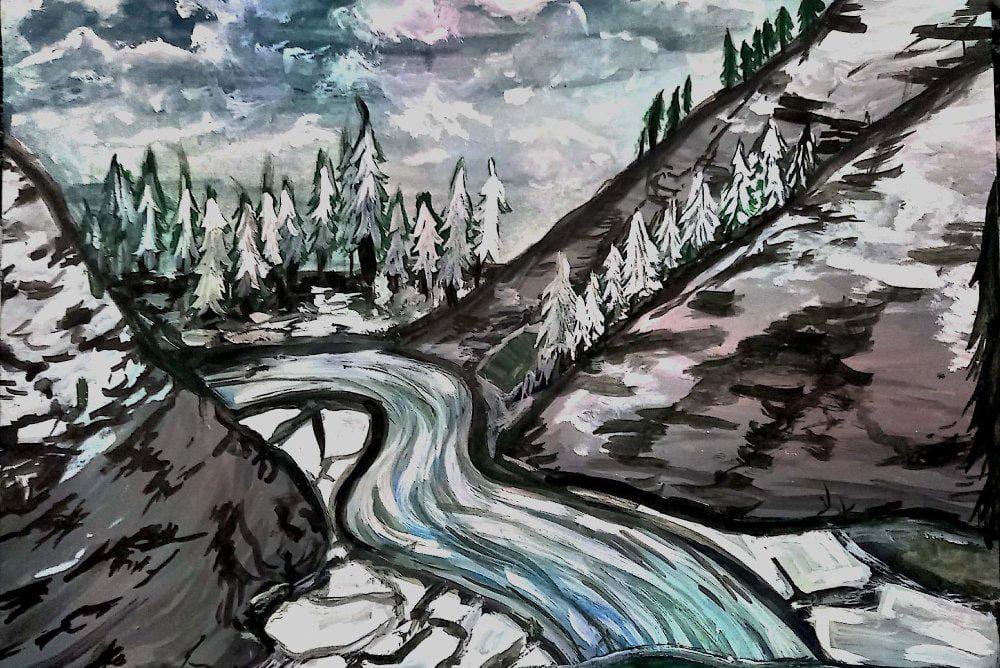

A father and son sat in the afternoon on top of a ridge on Kodiak Island their second day out. The boy glassed the back shoulder of the mountain, and the man scoped the valley in front. Franz Tabor had hunted and fished the Pasagshak for years and it was the best spot for Joey to bag his first deer. But after two days, it was beginning to look doubtful. Franz lowered his rifle and leaned it against the beveled rock ledge he rested against. What was left of the day was that still glow of full afternoon and the slow descent to camp, and Franz took a first pull from his flask of rye. He called this spot the Lookout for its commanding view over Rose Tead and the western mountains beyond. To the east it commanded the rolling foothill tundra that cascaded gently to the coast. The tarn below emptied into a tangle of oily braids that wove across the valley scrub over gravel spawning beds for a couple miles before emptying coldly into the pebbled beach of Pasagshak Bay. By Franz’s way of thinking, that made it the world’s shortest river. Today you couldn’t see the eight miles or so out to where the sheltered inlet opened into the chop of Ugak Bay. Only twenty miles to the east, in the imagination beyond the mist, Ugak emptied into the Gulf, waters he had crabbed and trawled for years before finding the sense to marry and come in a bit from the world’s edge. Ice had once covered this land, and it was the very ice that had drawn the seas back to reveal the Bering land bridge that had spawned the original American Dream. The ice formed giant thick glaciers that unlike the alpine variety that defined his own Austrian homeland, had flowed across the continent. The form of the bays and the shapes of the rock faces and hills and even Rose Tead itself, all owed their complexion to the sculpting power of the awful beautiful ice

“Where they at, Pops?”

Where were they at, Franz wondered. The Sitka black deer was an exotic, native to the rain forests down Juneau way. But they had flourished on Kodiak since their introduction nearly a hundred years ago. They were now a healthy stock and without any natural predators needed culling. And on that Thanksgiving weekend they happened to be in rut. It had been cold for November, and Franz’s calculations had them hunkered down in the valleys, so that’s where they had hunted yesterday. Skunked, he had settled on the highlands for today. At least the Lookout would provide him with the best lay of where tomorrow’s action might be. They had to pack it in Sunday morning to get back to town, so tomorrow was their last stand.

“Damned if I know,” he allowed.

His gaze drifted from the tiny outline of their camp nestled among the few scrubby cottonwoods on the near shore of Rose Tead out to the reeds of the shallows to a flock of mergansers floating on the still grey surface of the deep and beyond to the jumbled meadows of mountain alder and salmonberry on the far shore that scurried up the sere slopes all the way to the mean clouds enshrouding the blue crags that rose to the west. It had spit rain and sleet all day through wind gusts, but the air had gentled to an afternoon glow, and for a moment the lashing sky had stilled. A dampness inside his parka was the pebble in Franz’s shoe, and unsure how it had gotten through, he felt irritable and testy. He took another nip to walk himself back from that and stave off the chill.

“Dad, look!” Joey hissed tensely beside him. “A herd!”

The old man eased around the face of the outcrop and rested his .30-06 on a part of it and kneeled to scope the terrain. “Does,” he observed.

“I count six.”

“And a buck rising over the shoulder.”

“Dad, that’s a ten-pointer.”

It was a fine buck alright. “I’ll bet there’ll be a spike or two that follows him up,” Franz said low.

The animals below reminded him of American GIs in a long-ago Italian valley, a little closer and less wary, admittedly, the shot easier. The does pawed through patches of snow and foraged on something they clearly liked and were frisky. The buck cavorted about and stamped his feet and crowded the herd, and the does hopped away from him to resume their grazing nearby. Through the eight-power scope, the boy saw the buck’s breath stream powerfully from its nostrils as it bird-dogged the does. Franz’s range finder read 150 meters . . . a challenging shot for the boy. And there was 30 meters or so of relief, complicating the trajectory. A gust of wind brought a new spray of moisture, more ice than water, and the wind added yet another variable. He mulled the ballistics.

“It’ll be some work, even if I get my shot,” Joey whispered as they eyed the game. “Think it’s too late in the day?”

Franz yawned, and the distance suddenly did not seem so great, a gentle enough incline headed down the ridge that would be tougher humping back out under a load, but a cakewalk next to some things that you wound up doing. Still, it looked to be four hours of work to make camp, assuming a clean kill, and that was about two hours more than the light they had left. The mist slapped his cheek, and he was ready to move in one direction or another. The exertion and cold were exhilarating, and the rye made a warm hole in his belly.

“A doe will be better for the freezer than that trophy buck,” the boy allowed. “Look, Pops, there’s your spike!”

Sure enough, a bewildered juvenile popped over the ridge and watched the buck attentively, coveting the harem. “Maybe we should give junior a chance at that harem,” Franz said quietly. “You can fashion a fine knife handle from that old buck’s antler stock.”

“And there’s still time?” the boy contained his excitement.

“You’re gonna have to line up high,” his father replied.

“But not too high,” Joey made his voice mimic his father’s murmur.

“Yes,” Franz agreed, still studying it over through his scope.

“I’m sighted in at a hundred yards.”

“You’ll want to aim about forty-five centimeters above the withers, no lower than that.

“Uh.”

“It is like 19 inches.”

“A foot and a half,” Joey did the math.

“About half the height of his body.”

“What about the wind, Pops?”

“That can be your excuse if you miss.”

“I’m going to hold for a lull,” the boy announced.

“Get into the tunnel, Joe Joe. Remember . . .”

“Yeah, yeah, exhale slowly and squeeze gently.”

They did not need to be chasing a wounded animal into the falling night, and Franz got into the tunnel as well and lined out on his boy’s first deer to follow up as needed. A long time passed, and they were quiet, and the only sound was the wind that whistled in gusts over the ridgeline and the tiny pieces of ice that hit their clothing and packs and faces.

The crack that splintered the grey afternoon was the intersection of an axe and seasoned spruce and spread from the mountaintop in all directions and was held down by the clouds and wind so that the sound not allowed to escape into space bounced back to race around the ground into gullies and valleys and rise over knolls and hills and to echo for miles around and to find its way even out to sea. The buck fell in its tracks, and the old man lowered his rifle to watch the does scatter and the spike give chase, and he looked over at Joey. The ducks lifted from Rose Tead and by the time their distant squawks reached the Lookout, they were already in the air pulling into a flock. The two smiled at one another, and the old man chuckled.

“Nice shot, son.”

They stood and readied themselves, and the sleet turned wet and picked up. They tied their hoods down and shouldered the packs and rifles. “You dry?” the father asked his son.

“Yeah, I’m okay,” the boy replied. “My toes are nice and warm,” he said too quickly to check himself.

“This is going to be easy,” the old man said. He took another drink and jammed his mittens on tight, and they set off down the ridge, the long easy way down to where the animal lay, rather than straight down the steep slope. The wind picked up and the wet sleet turned to a light rain. They trundled down through patchy wet snow as the wind whistled above them. Once they were off the ridge, it was not as cold, and they made good progress, and after a while Franz began to perspire. Twenty minutes later as they came onto the shoulder and approached the kill, the buck came suddenly alive and made a frantic bound and leapt out of sight over the ledge and several hundred feet further down the mountain. It floundered in thick snow accumulated in a dark ravine.

“Should I shoot him again, Pops?”

“I think he’s done now,” Franz replied, looking down through the distance, admiring the new challenge.

“You okay, Dad?”

“Just been a long day is all. Let’s go take care of business.”

It was funny how moisture had found its way into his boots. The boy wore mukluks of course, but Franz preferred the leather hiking boots he had cut his teeth on as a conscript. He made a mental note to oil them back home. His double lining of socks—cotton inside of wool—would be good enough for today, but the little things mattered. Anyway, his feet were not wet, only moist—a little painful—but he had lived with that ugly memory for thirty years and knew how to manage it. And he felt damp on his sides as well, and that moisture, along with the sweat of a few minutes earlier was clammy as it thickened about his rib cage. He had a good mind to rest up, but when his son turned to the task, he drew up to soldier on.

The deer was still not quite dead, and Franz held the horns steady and cut its throat, and they watched as the animal bled out and its eyes dimmed. He slit the underbelly and turned the carcass over to the boy to disembowel and then walked him through the parts that followed. As he was showing Joey how to pull the skin away and slice at the sinew to separate it from the muscle, he carelessly nicked a finger but kept moving, his irritability pricked, and of course the boy noticed. But he talked himself down and had Joey take over and rubbed the blood off his hands with snow and drank again from the flask. Once the carcass was skinned enough, he showed Joey how to cut out the tenderloins from inside the cavity and then the loins on the back, pointing out where to cut and where to tease away from the bone and how to get it out neatly and whole. Joey bagged meat as the old man butchered. Nearing the end, Franz picked up his pace, and by the time he pulled the hacksaw out of the pack, he was moving pretty fast and roughly sawed the hams and shoulders away from the backbone and had Joey cut off the feet and antlers while he loaded the two packs, leaving the ribs, offal, head, and hide for the bears.

“It’s not very pretty,” he owned up. “But we got ground to cover.”

Joey beamed with pride as they readied their coats, gloves, zippers, boots, and shouldered their packs and rifles and turned back on their tracks. Franz led the way this time, powered by a new mystery and its fervent pulse. Once he had made it out of the bowl and back up to where the animal first fell the old man turned to find in his son’s eyes the pain from the work and the weight and felt the enormity in the process. When you parsed out all the nonsense, all that was left was feeding your family, and this what men did, and this was the kind of man that Franz wanted to by his own example make possible in his son. Joey’s torment was Franz’s elation, for this was something he had to understand, one of the things with which as a man, his son had by definition to be intimate.

A second wind filled Franz’s sails, and he whistled a Tyrolean folk song and marched briskly up the slope, slipping a bit in the sloppy mess their trail had become. He ignored the mist that blew in his face and wetted his neck and reached for his shoulders. As he backtracked up off the back bowl along the ridge, he gained distance on the boy, who nevertheless bore up magnificently under the load.

“Heavy isn’t it,” Franz shouted at his son, laughing.

“It’s killing me,” the kid allowed, managing to smile.

“Wanna rest?”

“No, let’s keep on. We’ll rest at the top,” the boy replied.

“Joe Joe, my man,” Franz smiled.

When they reached the Lookout, Joey could still just barely make out their camp down below in the shrunken light, but only because he knew where to look for it. He dropped his pack and plopped down on top of it, oblivious to everything but the searing of his chest as he caught his breath. He leaned against the cold hard ledge and found it forbidding, hardly the Sears Roebuck Lazy-Boy his pops seemed to breathe easy reclined against. The glacial bevel against which the old man reclined had lorded over the Pasagshak since practically the dawn of time and had been a favorite of Inuit hunting parties and lone grizzlies on the make ever since, and the occasional white man, and there was not likely any place on Earth quite as holy to Franz who drank it in by daylight, the whole valley below, its detail excruciating.

He scrounged around and lit matches to illumine the depleted reserves and shouldered a twenty-pound sack of sugar and slipped past the snoring guard into a moonless night and skirted the perimeter sentries to slip into the dark forest and headed south up the mountains. His odds were slim in February, but as the wolves of war closed in around a weakened stag, it was the only fighting chance he knew he could count on. He nursed the bag of sugar for two weeks and made the divide three days later, inured against his hunger, and willed himself down from the deep snow into Italy and ignored the numbness in his toes to tromp through what he believed to be the desert, unable in his hallucinations to prepare himself for the inevitability of his death. But God was not ready for him, and the devil was too distracted by Europe to take him, and he stumbled finally into a land below the thick snows where there were caves. He happened upon a shrunken bear emerged from his winter sleep and shot him and ate the meat raw for a day before laying up in a cave to amputate two black toes. He cauterized the stubs with his dagger and staved off the fantastic visions with grilled meat. He fashioned a camp to shelter the eternity it took to nurse himself back and adapt to his painful new gait to scout his uncertain new hopeful domain. In his gaining strength, he ducked the odd partisan bands but ventured farther afield in widening circles and trapped a couple hares and discovered aromatic herbs and other possible things to eat from the forest and speared trout as May lifted its hems in its skirmish up from the Mediterranean. His hideout was within the same limestone terrain where the Neanderthals were co-opted by his nimbler ancient ancestors and where the Romans first rubbed up against his pagan kindred tribesmen. To Franz, the weeks were months, and when he was sure the war had to be over, he strayed further and found a squad of well-fed Americans upon which he was able to sneak up in the night to drop his 98 and surrender on a June evening when they were fed and secure, and rather than shoot him on the spot, they took him prisoner, and by the time he found himself in a German POW camp in the strange flat land of Arkansas beside their great Rhine-like Mississippi, the Fuhrer was in his final throes in his Berlin bunker, and the Americans would not allow Franz to ship out to fight in the Pacific because of his feet. But they allowed him to stay in their land—his land now—and released him into the American heartland with a full set of clothing and shoes and ten dollars and told to go start a new life.

“Don’t you think we better be on our way, Pops?”

Franz mulled this a long time before finally replying. “Never want to get in too big a hurry, son,”

“I’m getting cold, Dad. I think we should move on.”

“Let’s gather our strengths a bit more here for a little spell, now that the rain has stopped. It feels so nice here, I could almost take a little nap.”

Of course, the rain had not stopped at all. “Well,” Joey chuckled awkwardly, “then you might want to let me hold the pistol in case a bear walks up on all this meat.”

The boy sure had a point there. Franz took another drink from the flask and found it nearly empty. “Good thinking, can’t be letting the bears have the stage…”

Sunset was not an event that you saw but rather a progression of deeper grays moving across the western sky, a hidden secret revealed only in clues of its passage, and by the boy’s estimation it was a full hour past sundown and pretty much dark-thirty at this point. They still had probably two hours hiking under the best of conditions, probably three as it stood with their load, and Pops all loopy. Joey wanted more than anything to be out of this rain and out of these clothes and off the mountain and swaddled in the flannel lining of his bedroll, but he and the old man rested a while longer instead in the wind and gently spitting rain and sleet, looking out on the night.

He might have wound up a cowboy in New Mexico or a roughneck in Wyoming or settled into a trade in California, but the sea that he looked out upon from the Columbia River delta drew him in with all the ferocity that his Atlantic crossing as a prisoner of war had pushed out of him, and he had broken his share of hearts in ports of call during his years at sea and drawn in shortening circuits around Kodiak, a land that seemed to mock all his voids as preternaturally full. He rented a room and shed his sea legs, tending bar and mending nets. He took classes at the community college and worked himself up to a degree and took the most beautiful girl in the whole world—a Ravistok, no less—and made her his wife and landed a job as a counselor at the Kodiak Junior High School, of which, fifteen years on, he was now the principal and the doting father of a first-born son twelve years of age and three darling daughters, ten, seven, and four. In the darkness shrouding the Lookout, his eyes wandered across the landscape and relived its features from a rare cloudless July day that he had hiked here years ago and seen it in all its splendid fully-lit brazen colors as far as the Earth’s curvature allowed. Tonight he saw all that and more, beyond the ocean’s curvature at will. But the vision that he settled upon to gentle in his bosom was that of little Sasha, darling Sasha, his middle daughter whooping with glee as her rod pulsed, dragging her madly along the gravel bar of the river now far below him, dazzling in today’s incredible light, the line zipping through the water, and the huge coho that she finally landed, Sasha’s eyes silver dollars, Joey and his sisters and mother rushing to corral and celebrate her exhilaration as the spent female gasped on the bank, eggs dribbling with finality from her vanquished body. That was earlier this morning or yesterday or last year or something, and dozens of bald eagles hopped around friskily to gorge on spent fish as the bears encroached, wary of the humans, but cued up for their rightful turn at the feedbag. He had vacuum-packed sixty pounds of smoked red and silver salmon in this year’s runs and had forty quarts pickled, all set up and dated neatly in the pantry. And there were a dozen pints of salmonberry preserves from June’s harvest and Darla’s labor over the stove and a good sixty pounds of frozen halibut from spring’s catch, enough to get them through the winter. There would be crab with the season coming on. Now, there was sixty pounds of venison from Joey’s first deer, meat they would eat fresh this week and freeze and jerky the rest . . .

After a long while of resting Joey nudged the old man, but from the resistance to his elbow, Joey knew his dad was dead. Pops’ eyes were open, and his look was curious and reposed, frozen in the middle of a pleasant surprise. Joey looked for a long time without moving to bend his mind around it. When he managed, finally, there was no room inside him yet for shock or emotion or anything but calculation and reason. He was in a spot of trouble, clearly, and Pops was not going to be able to get him out of this one, not this time. Joey frowned darkly at the turn of circumstance. He took off a glove and unzipped his father’s parka to pull out the revolver that hung from a shoulder holster and frowned at the dampness inside Pops’ coat. The white-knuckled boy stood and stilled his trembling hands to check the pistol’s load, relieved to see the bullets were hollow-points, and tested his flashlight against the evil night and recreated the topography in his head to navigate his way back to camp. The smell of the warm deer flesh from the butchering was thick on him, and he resisted a panicked urge to run out into the quickening danger. He left the rifles against the rock and the packs where they lay and bent down to look again into his father’s face before turning down the mountain to face the task with flashlights and a .357 magnum.

It took till noon the next day to get help from town back out and up the mountain. Joey led the party that later remarked at the cruelty of having that gruesome task after going through so much already. They tried to dissuade him, naturally, assured him they could find it from his description, but he wouldn’t have it; of course, sacred duty and all, however grim. They made it to Franz’s final lookout, and the rifles were lying there, unmoved from where Joey had left them. The packs were torn apart and pieces of shredded fabric were strewn about like piñata spew about the scene.

It took till noon the next day to get help from town back out and up the mountain. Joey led the party that later remarked at the cruelty of having that gruesome task after going through so much already. They tried to dissuade him, naturally, assured him they could find it from his description, but he wouldn’t have it; of course, sacred duty and all, however grim. They made it to Franz’s final lookout, and the rifles were lying there, unmoved from where Joey had left them. The packs were torn apart and pieces of shredded fabric were strewn about like piñata spew about the scene.

But there was no sign of the deer meat. And beyond ugly brown stains on the spotted snow and flecks of gore, there was no sign of Pops either.

The recovery party ushered the boy back down the mountain and into town and scoured the terrain for three days in search of some part of Franz Tabor they might turn over to his wife to bury.

Joey’s grandparents arranged a memorial service, and his mother was saved the cost of a coffin and a cemetery plot. She got a pension settlement from the school and social security, and since they owned the house outright, they never wanted, particularly given the prodigious pantry, and a few months later Mom took a secretarial job at the town law office and things moved on and after a year she remarried, and Joey and his sisters grew to accept their stepfather. Once Joey was legal to drive, he returned to Pasagshak in Pops’s rig to fish for reds in May, dollies in July and August, and Cohoes in September. He even made the pilgrimage with high school buddies over spring break his senior year and caught halibut out of Pops’s dory in the depths of gentle Pasagshak Bay. When his mom sold off the old man’s gun collection, Joey insisted on keeping only the .357 and a Beretta .12 gauge over-and-under but let her sell off all the other firearms without a peep. He killed a lot of ducks in his high-school years in the bays and marshes south of town, but he never got mad at the deer again, and he sold the revolver the July after graduation and took off fishing and then into the merchant marines to sail around the world. He stayed gone for so long that nobody recognized him when he stepped back many years later onto the Kodiak docks where the memory of his father had long melted into the rain that ran off the mountains and into the sea.